IS needs women and is using love as a recruitment tool

- Published

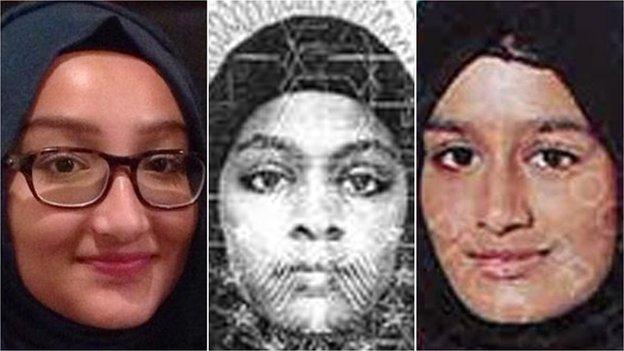

From left: Kadiza Sultana, Amira Abase and Shamima Begum know a girl who went to Syria in December

In a few months' time, perhaps even weeks, you might remember the story, but will you remember the names? Kadiza Sultana, 16; Shamima Begum, also 16; and Amira Abase, 15.

All three London schoolgirls said they were going out for the day and now it is thought they have left the UK, gone to Turkey and slipped across the border to join Islamic State (IS) militants in Syria.

Their names are important to me, because they focus my mind on them as individuals, as young girls, with a promising future ahead of them, with friends, siblings and parents.

Yet, inevitably, we are in thrall to the bigger narrative: a troubling and growing sisterhood is being cultivated - it appears an estimated 200 to 300 European Muslim girls have made the same journey as Kadiza, Shamima and Amira.

Why? What for? The term jihadi bride is particularly egregious, but there is some truth to it.

Recently, I met some mothers of sons and daughters who have decided to join the self-styled caliphate.

Three of the mothers had lost their sons in the fighting.

One woman, from Sweden, by way of Somalia, told me about her daughter, who was lured to Syria by a man she says she was in love with.

Her mother says IS use love as a recruiting tool. Once girls are persuaded that a warrior is in love with them, they in turn, can be used to recruit more girls and young women.

Building a state

We should, I suppose, remember it's a "state" that is being created. And it needs loyal subjects, not just fighters.

CCTV captured the girls passing through security at Gatwick Airport

It needs women, who will procreate.

Another mother, with an absent daughter, this one from Belgium, speaks to her daughter by text message regularly.

Her child also fell in love with a man thought to be a senior figure in the militant group.

She was telling her mother that life was good for her, but it wasn't long before that changed.

The reality and brutality made her uncomfortable, even as the partner of a senior jihadi.

After her daughter gave birth to a boy, the woman tried to arrange her departure, but she was treated violently by the man who she thought loved her.

It is unlikely that the now grandmother will see her daughter or her grandchild beyond the selfies she receives on her phone.

Impressionable

The British girls, Kadiza, Shamima and Amira are smart, promising students.

I suspect they don't think they have thrown their lives away.

Photographs of them at the airport show them striding with some determination.

But they are still just children. And we know how impressionable they can be, how easy to manipulate.

We know from Shamima's twitter account that she followed dozens of IS accounts, many of them women recruiters.

This appears to be an issue of radicalisation and grooming: a twin track of romanticising the life they will have as part of a battle sanctioned by God, alongside the actual romance they might have with a warrior in that battle.

When you are 15, that must seem so much more alluring than a day at school, especially if, like any other kind of sexual grooming, the victim genuinely believes the reality of their relationship with the adult.

One site, Ask FM, collects information about young Muslim girls in particular: how pretty they are, their height, their weight.

The only counter-narrative that might appeal to potential further recruits, is if girls such as Kadiza, Sultana, Shamima Begum and Amira Abase find a way of getting back to their lives in London, and tell the truth about how un-Islamic IS is; how unromantic it is to be part of a murderous cult and how unappealing it is to give up on your self, and your individuality.

But the vortex into which they have disappeared means that may never happen.

- Published22 February 2015

- Published6 October 2014