Nazir Afzal: Five things I've learned from Muslim women's groups

- Published

Nazir Afzal believes there are parallels between radicalisation and sexual grooming

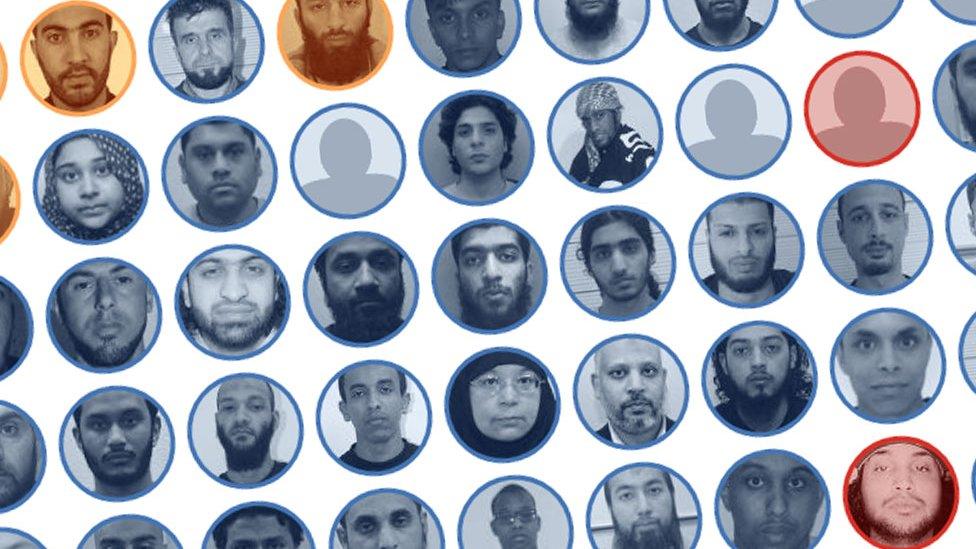

Hundreds of people from the UK have travelled to support or fight for jihadist organisations in Syria and Iraq, according to official UK figures. Most of them are thought to have joined the group that calls itself Islamic State.

But many organisations in the UK, set up by Muslim women, are now actively working to stop people joining extremist groups.

Nazir Afzal is a former chief crown prosecutor for the Crown Prosecution Service for north-west England. He prosecuted the Rochdale sexual grooming cases in 2012, and has also worked closely with these women's groups.

Here he outlines five things they have taught him.

1. Community schemes work best.

Government anti-radicalisation measures like Channel and Prevent, though said to be "tried and tested", are not working. The latest figures show that more than 1,000 people have gone to Syria. We need to replace these top-down schemes with ones based in the community, run by new people.

Women are key to combating radicalisation, to whom girls can go for reassurance, advice and pastoral care. And the state needs to ensure that any organisations it funds have at least 25% women on board, with the aim of increasing this figure to at least 50% in three years' time.

While I was Chief Crown Prosecutor I was privileged to work with dozens of women's groups, often from minority communities, working to protect our young. They get little recognition from the authorities, have to spend thousands of hours annually raising funds and even get attacked by men trying to put them down or worse.

Some of these women, in tackling violence against women and girls, have also been building the capacity and capability of other women and their families to prevent children being radicalised.

2. Radicalisation is about grooming the vulnerable.

The problem of radicalisation is misunderstood. Some suggest that it is a battle between two ways of life, when it is nothing more than the grooming of the most vulnerable by those who target them.

Grooming by extremists, like sexual grooming, is what it is: manipulation of the unwanted, their distancing from friends and families. And then they are taken.

Hundreds of Britons are thought to have joined the forces of the so-called Islamic State

But these women's groups have offered an alternative. I have seen young vulnerable people become volunteers in these groups and I have seen others re-engineer their lives so that their ambitions in the UK are fulfilled, rather than seeking escapism through those wanting to take them away.

The women have taken responsibility for the families, they guide the youth to safety and they protect us all from harm. They work "under the radar" and rarely get the recognition or the resources they deserve.

3. Men seeking control over women is the biggest contributing factor.

Time and time again I come across female victims of violence and abuse, especially Asian and Muslim, and I don't see broken women, I see women striving to ensure that others do not get subjected to their pain or, at the very least, signpost them to help.

It is extraordinary how many women who themselves have been abused end up running or working for organisations whose mission is to support other victims or educate to prevent harm in the first place.

Research suggests that Asian and Muslim women in particular are three times less likely to report their abuse than women from the majority communities.

In large part this is due to the issues of "honour" that pervade their communities and families. Asian women are regularly perceived to have dishonoured their families by talking about what happens behind closed doors.

4. Success is not measured by business cases.

Saeeda Ahmed is chief executive of Trescom, external, a community regeneration and training organisation based in Bradford.

While working on the time-consuming but successful task of bidding for public sector contracts, she has identified a cohort of young people who are at risk of being radicalised. They are disengaged from the mainstream and easily led.

But Saeeda doesn't want to waste time preparing a business case for state Prevent funding. She and her team just get on with mentoring those at risk, helping them to face their challenges and building their capacity to contribute to British society.

Three London schoolgirls are believed to be among those who have travelled to Syria

Rarely has anyone called me pompous but Saeeda tells it like it is or was. You wouldn't want to stand in her way when she's on a mission.

The same can be said of Shahien Taj of Cardiff's Henna Foundation, external, Sajda Mughal and the Jan Trust, external in London, Shazia Nisa and her Kaiza Project, external in the Midlands, Yasmin Khan and her Halo Project, external in the North East, Affrah Qassim and her Savera, external group in the North West and Anela Anwar and the Roshni, external team in Glasgow.

What do they have in common? These are Muslim women leading initiatives working to keep us all safe. They do it on a shoestring budget when state funding goes elsewhere.

Money and resources should be made available to grassroots activists like these, rather than for business plans to combat radicalism.

But, in many cases, local organisations are neglected in favour of groups that have the capacity, networks and organisation required to prepare business cases.

5. Doors open for them.

It is often "closed doors" in the community which hide young people at risk of being groomed by extremists.

Once these brave women have managed to enter these homes to provide support to victims or potential victims of abuse or forced marriage, they then open up avenues for dialogue about the other challenges these families face.

When gaining access to those at risk of radicalisation, these women refuse to take no for an answer. Their resilience is second to none. And their diplomatic skills mean that they are more successful than the police or a heavy-handed authoritative response might be.

One of these challenges is the alienation of their young and/or the poor communication that exists with these children. Too many of them have low aspirations and seek another path. Women like those I have mentioned are always keen to listen to the children and offer them hope where little exists.

It is easy to forget that unless we actively make it happen, the only role models they have are the ones that the media or online world gives them.

Nazir Afzal was the Chief Crown Prosecutor of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) for North West England from 2011-15.

Nazir Afzal's report will be on Newsnight next week on BBC Two and later on BBC iPlayer.

- Published12 October 2017

- Published6 October 2014

- Published13 November 2015

- Published2 September 2014