Azelle Rodney: Police shooter evidence explained

- Published

The prosecution submitted video reconstruction evidence as part of the trial

Why was a former police firearms officer found not guilty of the murder of a suspect he shot six times in 2005?

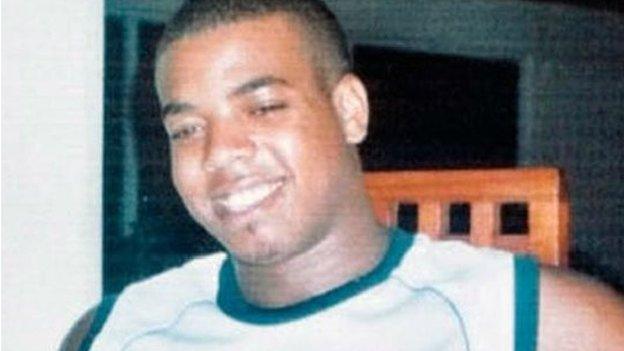

Anthony Long, who spent almost all of his career as an armed officer, shot dead Azelle Rodney after he and other officers surrounded the vehicle carrying the suspect and two accomplices.

Police believed the three men had planned an armed robbery of a Colombian drugs gang.

Anthony Long, 58, was a career firearms officer with commendations from both the Metropolitan Police's commissioner and a judge.

Mr Rodney, 24, was the third man he had shot dead. He had injured two others, one of whom was a man stabbing a four-year-old girl.

So what was so different about Mr Rodney's death that it led to Mr Long facing this exceptionally unusual trial?

The retired police officer had 30 years' experience of handling firearms when he shot Mr Rodney

Every armed police officer knows it is their decision alone if they choose to open fire. No superior officer can order them to do so - nor can a team take a pre-emptive tactical decision to shoot a suspect whatever the circumstances.

So a police officer can only justifiably open fire if he or she honestly believed that the trigger needed to be pulled to protect either himself, his colleagues or the public.

If someone is pointing a gun at someone in public, police would have little difficulty in convincing a court that they had to open fire.

But what if the officer was mistaken?

If their genuine belief is mistaken (such as in the case of the killing of Jean Charles de Menezes who police incorrectly thought was a suicide bomber) that isn't enough to charge an officer with murder.

The judge told the jury that under the law, a genuine belief can be brought about by panic so they could not find him guilty of that. So why did he end up on trial?

Mr Rodney died after armed police carried out a "hard stop" on his gang: Three cars surrounded and stopped the suspect vehicle - and then PC Long opened fire.

The video at the top of this page shows in detail what happened - it's a combination of the actual police footage and official reconstructions - and the detail within it, and the former officer's own account, are critical to understanding the case.

Judge's key question to the jury:

"Have the prosecution made us sure that, at the time that he fired his first shot, the defendant did not genuinely believe (even if mistakenly) that he and/or others were about to be fired at, so that he needed to defend himself and/or others by firing at Mr Rodney?

"If the answer is no, then you have reached a verdict of not guilty."

During the earlier wider inquiry into how Mr Rodney died, Mr Long said he honestly believed he had no choice but to fire. He said he was absolutely convinced that the suspect had ducked down to picked up a firearm. He said all of the suspect's body language told him that he and his colleagues were in imminent danger. Mr Long recalled these events at his trial.

The inquiry looked in detail at forensic reconstructions that cast doubt on Mr Long's recollection - and that led the inquiry chairman, Sir Christopher Holland, to decide that the police officer had "no lawful justification" for firing when he did.

That conclusion led to the former officer being charged with murder - and at the trial the prosecution had to leave the jury absolutely sure that the officer knew he didn't have to open fire.

'Split-second decision'

Prosecutor Max Hill QC told the jury that Mr Long's account could not be truthful because the defendant would not have had time to assess Rodney's intentions between his vehicle drawing alongside the suspect and the decision to pull the trigger.

"Mr Long opened fire extremely quickly," said Mr Hill. "So quickly we say, that he cannot have taken any time to observe anything happening inside the Golf before he opened fire."

For his part, Mr Long gave a detailed account of the final seconds - and as he left court, he said he stood by his decision to shoot.

"Police firearms officers do not go out intending to shoot people and like me in this case, have to make split-second life or death decisions based on the information available to them at the time."

- Published3 July 2015