7 July London bombings: The invisible victims

- Published

Shanie Ryan: 'Smoke was billowing in. Sounds of people screaming for help. I was screaming'

The 7 July London bombers killed 52 people and inflicted life-changing injuries on dozens more. But hundreds caught up in the blasts walked away that day - only to experience delayed emotional effects.

"It was a split second decision, that probably saved my life," says Shanie Ryan.

On that muggy Thursday morning 10 years ago, she was a 20-year-old dance student on her normal Piccadilly Line college commute with her flatmate Leon.

They were packed into their usual spot in the front carriage. As the train pulled into King's Cross, she jumped out to hug him goodbye.

Just yards away, bomber Germaine Lindsay was boarding the carriage.

Hearing the doors beep, Shanie turned to find her space gone. She hopped into the second carriage and squeezed in against the connecting doors.

Seconds later, as the train plunged into the darkness of the tunnel, Lindsay detonated his device.

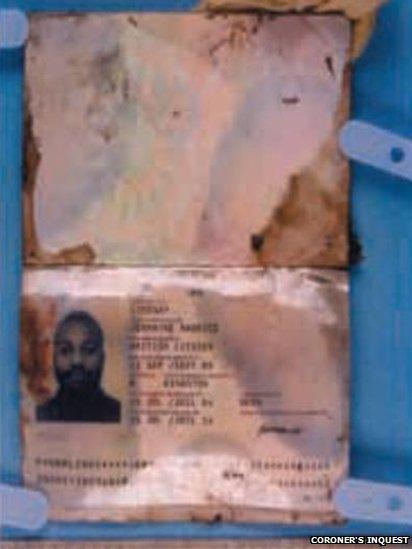

Germaine Lindsay's passport was found in the bombed carriage

Shanie has never spoken publicly about what followed.

"I just remember a huge bang. Pain in my ears. The train screeched to a halt and a woman fell on me. It was like time stood still. There was eerie silence - but loud, like white noise.

"Then it was senses coming back. Smoke was billowing in. Sounds of people badly injured, screaming for help. I was screaming, 'We're on fire', crying and panicking. The woman who fell on me - her name was Priscilla - picked me up and was saying, 'You're ok, you're ok'."

Not knowing what had happened, passengers started to debate what to do. Some of the men tried to break the windows. Others said they should wait for help.

But it would be a long wait - trapped behind the wreckage of the front carriage, they were stuck for more than an hour in the dark before emergency services reached them.

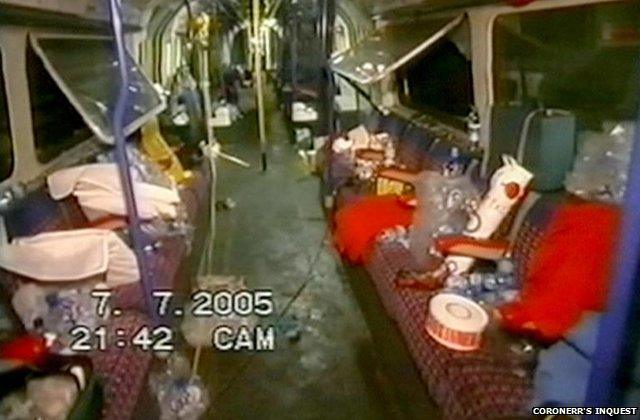

A screen grab from video footage taken by emergency services showed the scene of wreckage onboard the train between King's Cross and Russell Square

"People were comforting each other. All of a sudden strangers became so close. But at some point, we ran out of things to say and it went really quiet.

"That was when you really heard the hideous things next door. I was stood by the open window [between the connecting carriage doors], but I couldn't get in to help.

"When you're there and you can hear somebody's pain, and the whimpers are getting quieter, it's immediate guilt. That you can't help. That it's them and not you."

Read more

Twenty-six people died in the adjacent carriage, the worst of the four coordinated bomb attacks on London that day.

Eventually help arrived. Survivors were lifted out of the carriage, and began the long walk through the tunnel, past debris and body parts, still trying to work out what had happened.

One commuter took a photograph on his phone as survivors walked through the tunnel to King's Cross Station

Hundreds of people are thought to have walked away that day and never sought psychological treatment

As Shanie emerged into the light at King's Cross Station, a waiting paramedic tried to guide her towards an ambulance.

"I was saying, 'I'm fine, I'm fine'. I looked at the ambulance and there was blood everywhere and people gouged.

"I just snatched my arm away and ran, all the way to my college.

"I ran into Leon's morning ballet class and said, 'I think I've been in a train crash'.

"Everyone just stopped and stared, then Leon ran towards me. When I looked in a mirror later, I discovered I was covered in soot and dirt. Even my eyes were black. My tongue was black."

Police estimate that about 4,000 people were caught up in the blasts in some way.

Like Shanie, the vast majority of them were relatively physically unharmed. She suffered perforated ear drums and some breathing problems.

An unknown number of people simply walked away. Some even tried to wash off the debris and go to work as normal.

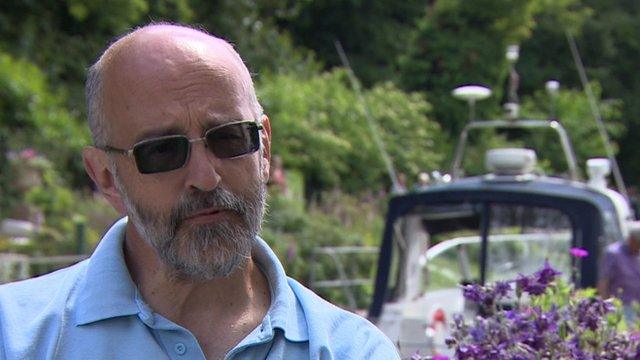

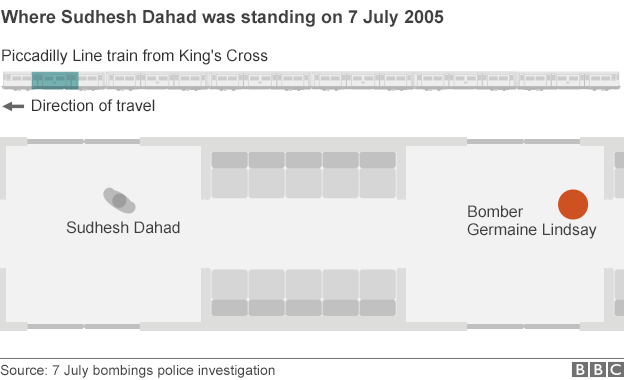

Risk analyst Sudhesh Dahad was also on the Piccadilly Line train, standing just six metres from the bomber.

He remembers a "popping noise", then coming round into a scene he describes as "Dante's inferno".

"I thought I was dead, and it was some kind of afterlife. From the sounds, I imagined it was people clawing, trying to get help, trying to pull themselves out of some kind of fire pit. Then I realised I was alive."

For Sudhesh Dahad, sounds and smells would trigger vivid flashbacks that he was back in the midst of the blast

Sudhesh was able to pick himself up, unharmed but for some cuts to his face and burst ear drums. The blood on his shirt wasn't his. Because he was ahead of the blast, the driver was able to lead them out through his cabin within 10 minutes.

By the next day, he was back to conference calls with colleagues in America and the demands of his high pressure job.

"I was still doing these things, but I was barely able to contribute. I was like a zombie.

"I just wanted someone to tell me what to do, but my boss said, 'Do what you feel is right'. I had no idea what that was."

While his physical wounds began to heal, his psychological ones grew worse: vivid flashbacks triggered by the slightest noise or smell, recurring nightmares that he was back on the train, overwhelming anxiety that it would all happen again.

Police came to collect his blast-tattered clothes as evidence and took a statement. He thought, "Good, I'm in the system". But there was no follow up of help.

From 2006 to 2010, Sudhesh immersed himself in work, until the feelings became overwhelming.

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, New York City's health department estimated 61,000 people suffered "probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)".

Psychologist Patricia d'Ardenne, head of the NHS's Institute of Psychotrauma in east London, says she knew on the day of 7/7 there would be hundreds, if not thousands, of people like Sudhesh and Shanie at risk of developing future mental health problems.

The problem was tracking survivors down.

What is PTSD?

Post-traumatic stress disorder is an anxiety disorder caused by witnessing or being involved in a frightening or distressing event.

People naturally feel afraid when in danger, but the legacy of some traumatic events is a change in perception of fear.

They may feel stressed or frightened in day-to-day life.

"On the day, the focus was evacuating people. People were told, 'Go, get away as fast as you can', because no one knew whether there would be more explosions.

"No names were even taken. We recognised that we needed to screen a large number of people. We knew what we'd lost."

Within two weeks, Dr d'Ardenne and a team of clinicians had set up five treatment centres around London, that they advertised however they could.

But very few GPs referred patients, and some hospitals said they could not share names of patients because of data protection laws.

Survivors themselves often felt guilty about seeking treatment, she says.

"They thought, 'I should thank my lucky stars. That person on the news lost their legs. If I've got difficulties, that's tough'."

Guilt was one of the strongest emotions experienced by the survivors; guilt that they had left injured people behind, and guilt that they had lived when others had died.

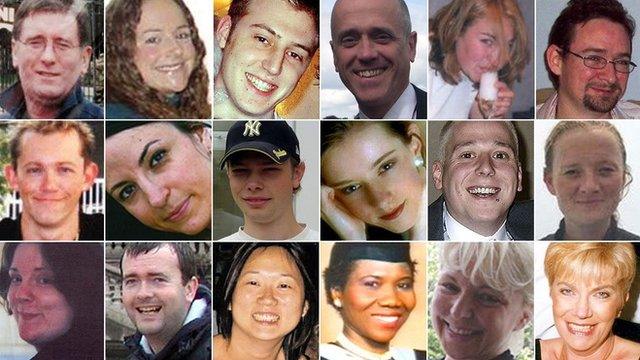

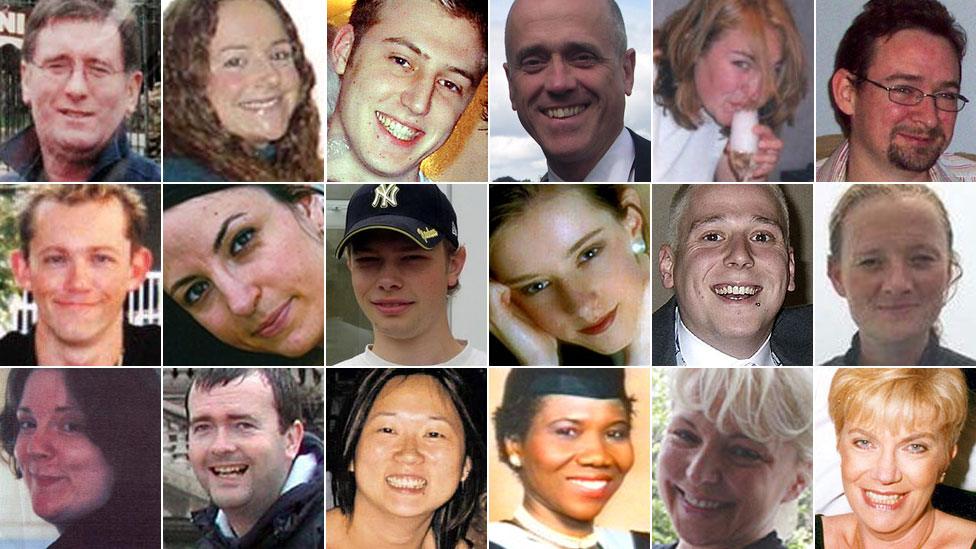

The victims

A total of 52 people lost their lives when four suicide bombers attacked central London 10 years ago. Here are their stories.

"Some said, 'I should have stayed. I should have done more," Dr d'Ardenne explains.

"Our treatment is about going back over the story many times, and slowly a fuller picture emerges - that there were emergency staff arriving in the carriage and shouting, 'Get out'. That you are not a first aider, you are a victim."

Dr d'Ardenne's team managed to identify and contact about 900 people for psychological screening.

Roughly 600 had the screening, of whom almost half had mental health problems severe enough to require treatment.

Commonly, people were experiencing flashbacks, hyper-vigilance "as though they were in a war zone", and phobia of public transport.

"We spent a lot of time escorting people who were very fearful of getting back on the Tube. They were walking five, six, seven miles a day to avoid it."

This involved comforting people when they needed it, and talking through their emotions.

But facts and information also mattered, she says, to help people rationalise what had happened, and how small the chances were of it happening again.

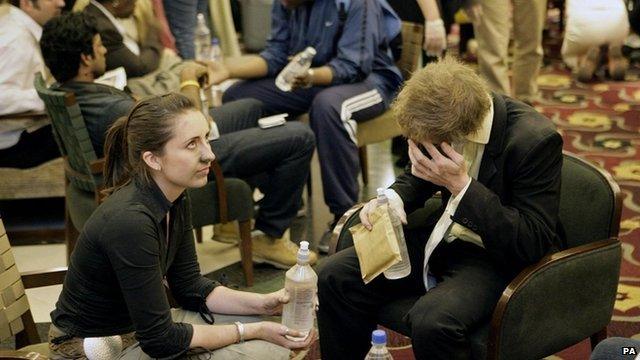

Near Edgware Road, the walking wounded were treated at the London Hilton Metropole

One patient - so unlucky as to have also been caught up in a previous terrorist attack - was only reassured after being taken to a bookmakers to see how long the odds were of being in a third.

That said, a failed attempt by bombers to attack London's transport network again, exactly two weeks later, raised fear levels further. It was the day of Shanie Ryan's first trip back on the Tube and she was evacuated at King's Cross again.

But as well as usual symptoms, Dr d'Ardenne and her team began to discover some unexpected psychological reactions, unique to 7 July survivors.

"We found people were not angry. They did not blame al-Qaeda [which later claimed responsibility for the attacks]. They did not blame the bombers.

"The people they blamed were quite curious. They blamed the government and foreign policy. And they blamed themselves. [One person] thought they were being punished."

Secondly, the team found that while survivors felt alienated from the normal world, they felt a great affinity with other survivors, "almost like a tribe apart".

Sudhesh recognises these feelings. He says he doesn't have any emotions about the bombers: "They were just puppets really, brainwashed".

What helped him most was a group set up by survivors called King's Cross United that helped him realise "it was ok to feel what I was feeling". Fellow member Angela Ioannou, who was in the third carriage of the train, and also diagnosed with PTSD, says the bond between some of them is "like family".

Five fellow 7 July survivors were at her wedding last year.

"It's a link we'll always have," says the north Londoner.

7/7 survivors now firm friends Tim Coulson, Joanne Cole, Angela Ioannou, Jacqui Putnam and Ellie Thompson at Angela's wedding

"It was very difficult to talk to others around me at that time. They had no idea of the anxiety, the fear, the guilt. It was a relief to know it wasn't just me feeling like that."

The positive effects of peer support for survivors of major terrorist incidents has begun to change how treatment is planned in case of future attacks. The Foundation for Peace in Warrington, set up in the wake of a 1993 IRA bomb, runs a Survivors Assistance Network for anyone affected by terrorism, grant-funded by the Ministry of Justice.

It is already preparing to offer support to survivors of the recent shootings in Tunisia.

The authorities know they need to act faster to record contact details of those affected, and Cabinet Office guidance means that hospitals should in future share survivor details with mental health teams.

They are lessons learned the hard way from 7 July 2005, when Dr d'Ardenne believes as many as 2,000 people may have slipped through the cracks.

For Shanie, it was eight years before she sought professional help, and was finally diagnosed with PTSD. The presenter and beauty expert from south-east London says she will never again be the fearless, carefree girl that stepped on to that train.

She still struggles with catching the Tube, and guilt in the form of an "overwhelming need to achieve, because others didn't get that opportunity".

But a decade on, she can see some positives.

"I've always been a go-getter, but it's pushed me to achieve more. I've travelled the world, I've raised money for charity, I've had a record deal, I've presented for MTV.

"And on that day on the train, I didn't see one selfish person. It was at once the awful side of humanity, but also the magical side."

Were you one of the hundreds who were caught up in the blasts and walked away? You can share your experience by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

If you would be happy to speak further to a BBC journalist, please include a contact telephone number when emailing us your details.

Or WhatsApp us on +44 7525 900971

Send your pictures and videos to yourpics@bbc.co.uk, external, text them to 61124 (UK) or +44 7624 800 100 (international) or via our WhatsApp number +44 (0)7525 900971 .

You can also upload here, external.

- Published3 July 2015

- Published4 July 2015