How NSA and GCHQ spied on the Cold War world

- Published

Hagelin developed the CX-52

American and British intelligence used a secret relationship with the founder of a Swiss encryption company to help them spy during the Cold War, newly released documents analysed by the BBC reveal.

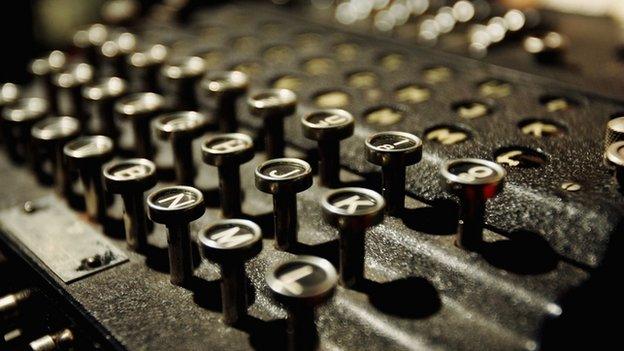

The story of the German Enigma machine is well-known - a device built to provide secure communications but which British code-breakers managed to crack at Bletchley Park.

But there is another story - not fully told until now - about what came after.

The demand for machines like Enigma grew after the end of the World War Two. And one private company led the way in meeting that demand.

That company, founded by a man called Boris Hagelin, was called Crypto AG.

Enigma played a key role in the World War Two

Hagelin had helped supply the US Army during the War before moving his business from Sweden to Switzerland.

Crypto AG sold its machines around the world, offering security.

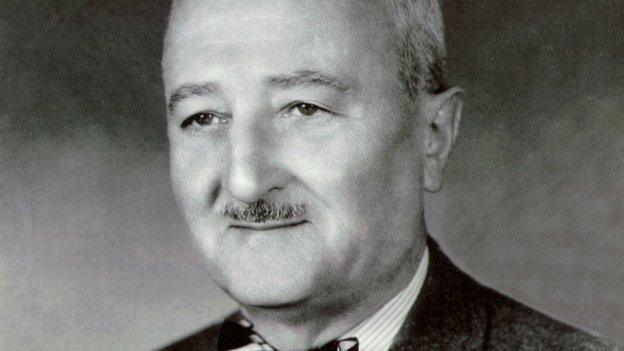

But what customers did not know was that Hagelin himself had come to a secret agreement with the founding father of American code-breaking, William F Friedman, external.

Reports of a deal have circulated before.

In the 1980s, the historian James Bamford was researching his book The Puzzle Palace about the US National Security Agency (NSA) and came across references to the "Boris project" in Friedman's papers.

The NSA promptly had the papers locked up in a vault.

In 1995, journalist Scott Shane, then at the Baltimore Sun, found indications of contacts between the company and the NSA in the 1970s, but the company said claims of a deal were "pure invention".

The new revelations of a deal do not come from a whistleblower or leaked reports, but are buried within 52,000 pages of documents declassified by the NSA itself this April and investigated by the BBC.

Top-secret report

The relationship was based on a deep personal friendship between Hagelin and Friedman, forged during the War.

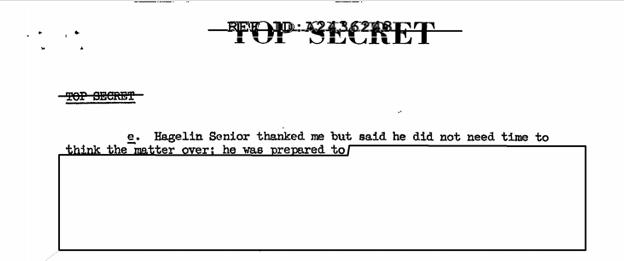

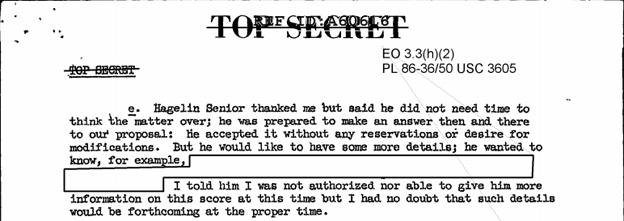

The central document is a once top-secret 22-page report of a 1955 visit by Friedman to Zug in Switzerland, where Crypto AG was based.

Some elements of the memo have been redacted - or blacked out - by the NSA.

But within the released material, are two versions of the same memo, as well as a draft.

Each has different parts redacted. By placing them side by side and cross referencing with other documents, it is possible to learn many - but not all - details.

The different versions of the report make clear Friedman - described as special assistant to the director, NSA - went with a proposal agreed not just by US, but also British intelligence.

Friedman offered Hagelin time to think his proposal over, but Hagelin accepted on the spot.

Different versions of the report:

Redacted text

Differently redacted text

The relationship, initially referred to as a "gentleman's agreement", included Hagelin keeping the NSA and GCHQ informed about the technical specifications of different machines and which countries were buying which ones.

The provision of technical details "is a revelation of the first order," says Paul Reuvers, an engineer who runs the Crypto Museum website.

"That's extremely valuable. It is something you would not normally do because the integrity and secrecy of your own customer is mandatory in this business."

Machine specifics key

The key to breaking mechanical encryption machines - such as Enigma or those produced by Hagelin - is to understand in detail how they work and how they are used.

This knowledge can allow smart code breakers to look for weaknesses and use a combination of maths and computing to work through permutations to find a solution.

In one document, Hagelin hints to Friedman he is going to be able "to supply certain customers" with a specific machine which, Friedman notes, is of course "easier to solve than the new models".

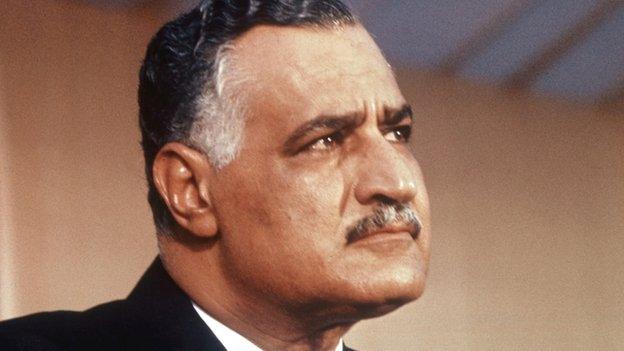

William Friedman seems to have struck a deal

Previous reports of the deal suggested it may have involved some kind of backdoor in the machines, which would provide the NSA with the keys.

But there is no evidence for this in the documents (although some parts remain redacted).

Rather, it seems the detailed knowledge of the machines and their operations may have allowed code-breakers to cut the time needed to decrypt messages from the impossible to the possible.

The relationship also involved not selling machines such as the CX-52, a more advanced version of the C-52 - to certain countries.

"The reason that CX-52 is so terrifying is because it can be customised," says Prof Richard Aldrich, of the University of Warwick.

"So it's a bit like defeating Enigma and then moving to the next country and then you've got to defeat Enigma again and again and again."

Some countries - including Egypt and India - were not told of the more advanced models and so bought those easier for the US and UK to break.

In some cases, customers appear to have been deceived.

One memo indicates Crypto AG was providing different customers with encryption machines of different strengths at the behest of Nato and that "the different brochures are distinguishable only by 'secret marks' printed thereon".

Historian Stephen Budiansky says: "There was a certain degree of deception going on of the customers who were buying [machines] and thinking they were getting something the same as what Hagelin was selling everywhere when in fact it was a watered-down version."

Were the machines used to decode messages from Nasser's Egypt?

Among the customers of Hagelin listed are Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Pakistan, India, Jordan and others in the developing world.

In the summer of 1958, army officers apparently sympathetic to Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the regime in Iraq.

Historian David Easter, of King's College, London, says intelligence from decrypted Egyptian communications was vital in Britain being able to rapidly deploy troops to neighbouring Jordan to forestall a potential follow-up coup against a British ally.

The 1955 deal also appears to have involved the NSA itself writing "brochures", instruction manuals for the CX-52, to ensure "proper use".

One interpretation is these were written so certain countries could use the machines securely - but in others, they were set up so the number of possible permutations was small enough for the NSA to crack.

The NSA has been based in Fort Meade for decades

In the 1955 memo, Friedman told Hagelin he was well aware of the businessman's "disinclination" to be paid as part of the deal.

However, Hagelin went on, according to the memo, to express his gratitude to the NSA for "what we had done and were continuing to do for various member of his family".

This included intervening to ensure a son-in-law had his active duty status in the US Air Force retained and a cousin of Hagelin's wife seemingly being employed at the NSA.

Crypto AG chief executive, Giulliano Otth refused to comment on the "intense private dialogue on various personal and professional subjects" that had grown out of the friendship between Friedman and Hagelin in the 1950s.

The company now "enjoys an excellent reputation with all its customers", and the algorithms used in its modern products gave customers exclusive control, he told the BBC.

"That is why it is technically impossible for third parties to exert influence. Not even Crypto AG has access," he said.

In a statement, a GCHQ spokesman said the agency "does not comment on its operational activities and neither confirms nor denies the accuracy of the specific inferences that have been drawn from the document you are discussing".

GCHQ: the centre of the UK surveillance operation

"The documents... should be read against a background in which the UK, the US and their allies faced the likelihood of open hostilities with the Soviet bloc," he added.

The NSA also declined to comment on the specific conclusions.

But its associate director for policy and records, Dr David Sherman, told the BBC: "It is not surprising to me that [the US and UK] would be very concerned about the security of the communications of those West European countries - [and] want to know what systems they might be using so that the now sensitive communications of the Nato alliance are not vulnerable to penetration by the Soviet Union.

"And simultaneously I think they are very concerned not to allow what we now call strong encryption - powerful encryption products and machinery - to fall into the hands of their adversaries including the Soviet Union and others."

You can listen to Document: The Crypto Agreement on BBC Radio 4 at 16:00 BST on 28 July.

- Published5 May 2014

- Published9 March 2012