How GCHQ built on a colossal secret

- Published

Wartime work on Colossus kicked off a close relationship between spies and computers

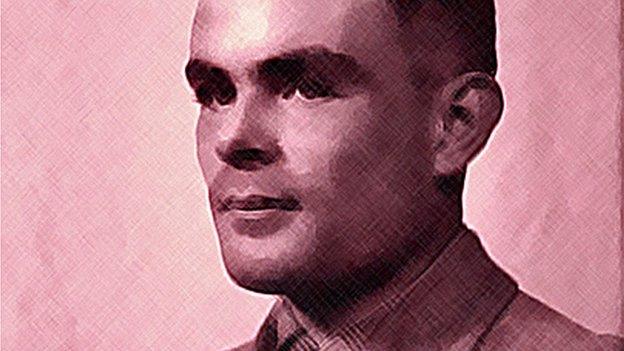

During World War Two, Britain led the world in its creation of machines that excelled at cracking codes used by its enemies.

Messages scrambled using the Enigma machine were cracked by devices largely designed by maths genius Alan Turing.

In addition, the Allies' preparations for D-Day were greatly helped by a pioneering computer called Colossus which helped to decipher messages passing between Hitler and his generals in hours. Without its help, reading those messages took weeks.

Colossus was kept secret for decades after the war and it is only recently that a full picture of its influence and engineering brilliance has become apparent.

Mobile data

But it was not the only code-cracking computer that Britain made. Steadily more details are emerging of the secret machines that came after Colossus and surpassed its ability to unscramble messages.

A total of 10 Colossi were made during WW2 and once hostilities ceased eight of them were broken up and the plans for them destroyed.

Two were kept and were used to help Britain's GCHQ keep cracking codes.

Bletchley veteran John Cane helped maintain the Colossi during the war and stayed on afterwards to oversee the two remaining machines move first to Eastcote in North London and then on to Cheltenham - where GCHQ is sited to this day.

Moving these delicate machines was a tense and nerve-racking experience, said Mr Cane.

"We called on the owner of an enormous crane and very gingerly the whole of this mass of switches and wiring was hoisted into the air and then lowered through a hole in the roof and then planted safely on the floor," he said.

GCHQ has been a centre for computer development since its inception

Mr Cane told the BBC that the two Colossi, dubbed "Red" and "Blue", were extensively modified after 1945 to make them less prone to breaking down and to make it easier to input data.

Blue was kept true to its original purpose of targeting messages scrambled with the Lorenz enciphering machine that some nations were still using long after the war ended. The remaining machine, Red, was changed to be more general so it could be used against other targets.

But GCHQ's work on special-purpose machines did not stop with Colossus, said Mr Cane.

Between the end of WW2 and the early 1960s engineers at GCHQ finished work on machines called Aquarius and Robinson whose development had started in the huts at Bletchley. They also brought into being others called Colorob, Dragon, Johnson and Oedipus.

Modern mainframes

Prof Simon Lavington who has written extensively about early British computers said Oedpius was "quite a machine" in that it was probably faster and used more online storage than almost any other computer in existence at the time. It was one of the first to properly deserve the name of "supercomputer".

The first three letters of the machine's name, OED, gave a clue to its use, said Prof Lavington, in that it had a large dictionary at its core and was used to look up and compare words and phrases. It is thought this was used to target messages scrambled with systems that did not rely on machines to encrypt them.

Unfortunately the secrecy surrounding the machines had its downsides, said Mr Cane.

"What I do remember about Oedipus was that the two halves of the machine were built by two separate companies," he said, "and when they came to join them up they found that the interfaces did not match."

GCHQ was one of the first places in the UK to procure one of the distinctive Cray supercomputers

Despite this, GCHQ was a real centre of computer development and innovation, said Prof Richard Aldrich from the University of Warwick who wrote an unofficial history of the agency.

GCHQ's development of special purpose machines largely ended in the 1960s as powerful general purpose computers became available. As a result the development focus switched from hardware to software, said Prof Aldrich. Additional pressure to use such machines was added by the close relationship developing between UK and US spying agencies.

"Because essentially the story of GCHQ is that they wanted to co-operate with the US so they were pretty much the only government organisation that was allowed to buy IBM mainframes," he said. Other departments were mandated to buy from the government-backed computer company ICL in a bid to preserve home-grown technology.

GCHQ was also probably one of the first places in the UK to get a Cray supercomputer, he added.

That relationship with the US led GCHQ to become a place to store the huge amounts of telephone call data that American intelligence agencies were scooping up. This helped to cement the close relationship between GCHQ and the Post Office. For instance, he said, the two collaborated extensively on ways to automatically recognise who is talking during a phone call.

"It's not just about code-cracking," said Prof Aldrich. "Computerisation is fundamental to everything GCHQ does."

- Published7 February 2014

- Published1 August 2013

- Published20 June 2012