Litvinenko inquiry: What we know about the case

- Published

Alexander Litvinenko died in hospital in London in November 2006

The public hearings of the inquiry into the death of Alexander Litvinenko are now drawing to a close after months of evidence.

It was the most dramatic of murders - what one lawyer called "an act of nuclear terrorism" on the streets of London - and the victim was a man who had once worked for the Russian security services but was later on the payroll of their British counterparts.

So what have we learned about the man, how he died and who was behind it?

Alexander Litvinenko

The inquiry has delved deep into Alexander Litvinenko's past and particularly his falling-out with his employers in the Russian security service in the late 1990s - then headed by Vladimir Putin.

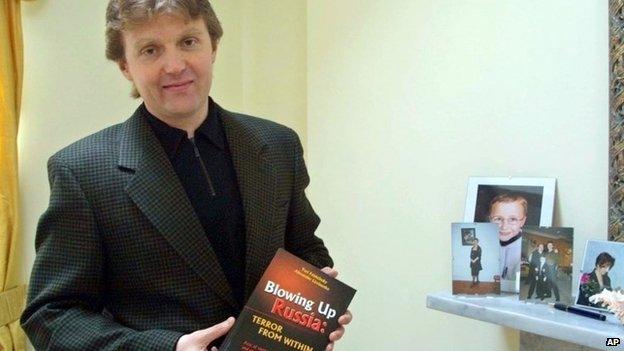

We heard about his fleeing to London and then his subsequent vocal criticism of Mr Putin, which included accusing the Russian leader of being behind apartment bombings in Moscow.

Mr Litvinenko had a close relationship with exiled tycoon Boris Berezovsky and Chechen exiles in London, as he also worked on investigations into Russian businesses and individuals for private security firms.

Just before he died, Mr Litvinenko had been proud to have become a British citizen.

The inquiry also learned about his relationship with MI6, including the fact he received regular payments form the British secret service and had a handler codenamed Martin.

The death: Polonium

There has never been much doubt that Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned with radioactive polonium.

But we learned much more about how this was discovered, almost by chance, as he lay dying after weeks of tests and growing confusion about his illness.

Polonium was described as an "almost perfect murder weapon" - but once it had been discovered, a trail could be followed that extended across the capital and beyond.

Police said they would never know what long-term dangers exposure to it could mean for the public.

Some 97% of the world's polonium, the inquiry heard, came from Russia.

How it was done

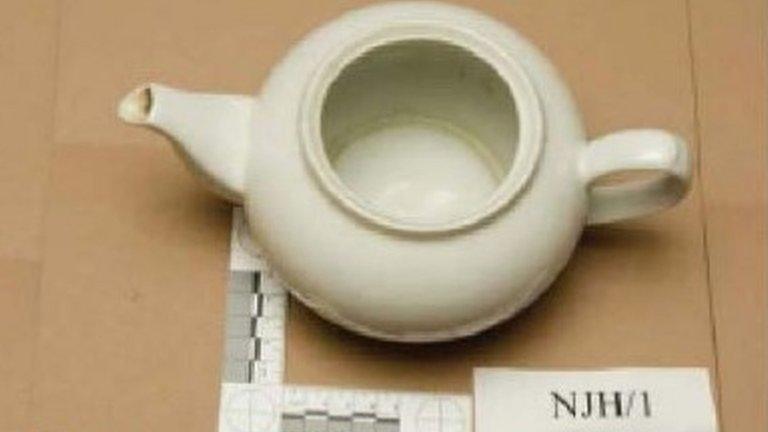

The evidence pointed - as had always been suspected - to the poison being delivered in a cup of tea in the Pine Bar of the Millennium Hotel in Grosvenor Square, London.

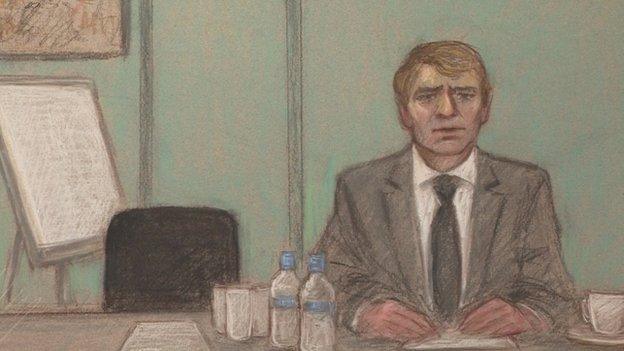

Andrei Lugovoi denies any involvement in the death of Mr Litvinenko

A teapot showed very high traces of radioactivity on the spout consistent with it having been used to pour the polonium out.

At the bar, Alexander Litvinenko met the two alleged killers, Dmitry Kovtun and Andrei Lugovoi.

Both men deny they were involved in murder.

The police suggested, though, that while the alleged killers knew they were carrying a poison, they did not know it was radioactive.

That, police said, explained why Mr Lugovoi was willing to have his family in close proximity and even shake Mr Litvinenko's hand after the poisoning.

The inquiry also heard testimony from unnamed individuals who suggested that in Germany, Dmitry Kovtun had also asked a friend to find a cook who could administer what was called a "very expensive poison" in London.

The alleged killers

The evidence linking the two alleged killers - Dmitry Kovtun and Andrei Lugovoi - was primarily forensic.

Police were able to correlate their movements with the trail of polonium, not just in London but further afield.

Dmitry Kovtun had been expected to appear by video link from Moscow

This related to flights they took, bars they visited, the Emirates football stadium where they saw a game, Mr Kovtun's movements in Germany and even a visit by them to the British Embassy in Moscow after the murder.

Dmitry Kovtun had been due to give evidence in the final days of the inquiry but raised last-minute concerns that doing so would breach confidentiality agreements with Russian investigators.

This meant neither of the men was able to answer or challenge the evidence against them directly.

Other theories received limited attention in the inquiry.

The police dismissed the claim that Litvinenko himself had somehow been involved in smuggling polonium or that MI6 framed Lugovoi and Kovtun.

Suicide was also ruled out and while there was some evidence that Litvinenko's relationship with Boris Berezovsky had cooled, there was nothing to suggest that this could have led to his death.

The role of Russia

Neither Lugovoi nor Kovtun were said to have had a personal motive for murdering Litvinenko and so the belief was that they must have been acting on behalf of someone else.

The use of hard-to-find polonium was another factor.

Mr Litvinenko criticised his former employer in a book published in 2002

"The evidence suggests that the only credible explanation is that in one way or another the Russian state was involved in Litvinenko's murder," the lawyer for the police, Richard Horwell QC, said in his closing statement.

He was careful, though, not to say that this had to mean that Vladimir Putin gave the order.

Ben Emmerson QC, lawyer for Litvinenko's widow Marina, however, said in his closing statement that the evidence pointed to Mr Putin.

"When the evidence is viewed in the round, as it must be, it establishes Russian state responsibility for Alexander Litvinenko's murder beyond reasonable doubt. And if the Russian state is responsible, Vladimir Putin is responsible."

Alexander Litvinenko's problems with Russia's leader began when he was an FSB officer in the late 1990s and complained to Mr Putin, then the director of the security service.

His fierce criticism of Mr Putin continued after he fled to London, when he was seen by some in Russia as a traitor.

He was also investigating corruption among senior individuals and links to the mafia.

In the summer of 2006, changes to a law permitting the elimination of "extremists" gave it a wide definition that the police said could have included Litvinenko.

No conclusive evidence was heard in the inquiry as to who might have given the order although various theories were raised.

Secret evidence heard by the chairman of the inquiry, Sir Robert Owen, may include further intelligence on this specific issue, which is why his willingness to point the finger will be so closely watched and may determine how much diplomatic fallout there is from the inquiry.

He is due to deliver his report to the home secretary by the end of the year.

- Published28 July 2015

- Published30 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015

- Published21 January 2016