The big remaining questions for Kids Company's trustees

- Published

- comments

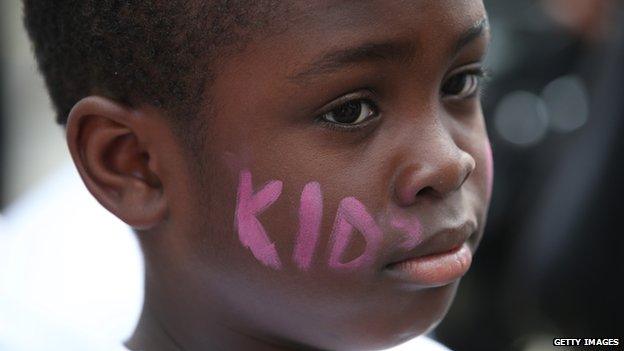

There are been a number of demonstrations in support of Kids Company

As local authorities and charities have started helping people stranded by the closure of Kids Company, the big concern is still about how to provide support for young people who used the charity's services, particularly in its south London heartland. A police investigation involving the charity is, quietly, still interviewing former staff members and clients.

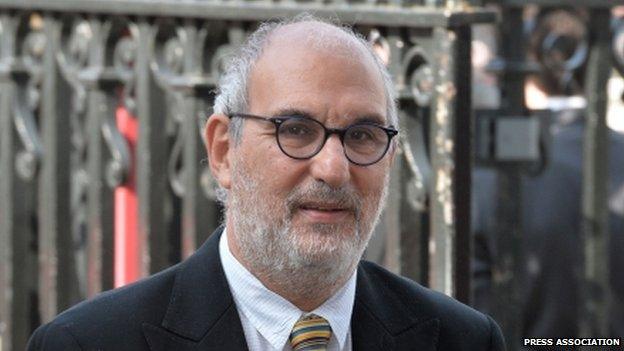

In the medium term, though, attention must turn to the Kids Company's trustees, who have legal responsibilities for the charity. Chaired by Alan Yentob, the BBC broadcaster and creative director, the trustees clearly made strategic decisions that repay some examination.

First, allegations from former staff to a joint investigation by Newsnight and BuzzFeed News raised concerns that the charity's safeguarding procedures were insufficiently robust.

Second, the charity failed to build a serious evidence base behind its work. That made it hard even for lots of very sympathetic funders to back it. We do not know how many young people used the service, let alone how many got qualifications, jobs or were spared prison because of its work.

Even the most-cited academic assessments of the charity's work, external are not useful to this end. This was a strategic weakness of Kids Company, and one that the trustees should have considered; it made bidding for public money, in particular, unnecessarily difficult.

Third, Kids Company was run with an unusually threadbare financial safety net, which made it more vulnerable to financial shocks than it ought to have been. The finances of the institution have long looked precarious - especially for a charity whose clients are so reliant upon it. That was evident from its last accounts, which are from 2013, external.

Demonstration to save Kids Company last week at Downing Street

Keeping money in reserve

A normal rule of thumb, used across the voluntary sector, is that charities should hold three months of spending in unrestricted reserves. The average quantity of reserve cash held by charities in the same sector as Kids Company is a bit more than five months of spending, external. For a charity spending £23m a year, as Kids Company did in 2013, three months of reserves would be roughly £6m for emergencies.

That benchmark number might be unfairly high. It might be fairer to use the "core" costs of the charity for this spending benchmark. On that basis, it spent £15m per annum keeping its staff paid and the premises open. Using that figure, which is the cost of keeping things ticking over, would imply that the charity would need to have a rainy day fund of about £4m in reserves.

According to the charity's last annual report, its unrestricted reserves were just £434,282 in 2013. It had a further £1.3m in restricted reserves and designated funds - money which could only be used to particular ends. That category might have helped it cover elements of the charity's operations, were it to have run into trouble. But even so, the charity looked poorly provisioned.

Building an unrestricted reserve of £6m would mean keeping 7p in reserve for every pound that the charity spent over the five financial years from 2009 to 2013 - a period when the charity was growing fast. Had it done that - which would have required slower growth in service provision rather than cuts - the charity would have been better placed to survive.

It seems unlikely, even then, that the charity would have continued in anything like its prior form. The collapse in private donations has been both rapid and extreme this year.

Former funders have told us that they pulled out because of concerns about management, but it is fanciful to suggest that a lack of reserves was the only reason for their scepticism.

Alan Yentob, chair of Kids Company trustees

Calling it a day

A decent reserve, however, would have left the charity able to downsize, restructure or move to a new model. Were it still impossible for Kids Company to survive, it would have allowed the trustees to wind down the charity in an orderly fashion. Staff would have been paid in full and there could have been a careful, slow triage and handover process for vulnerable clients.

In addition to long-term financial questions, though, any investigation - and the charity's taxpayer income means there surely will be one - is likely to look into the trustees' judgments in the past few months about the charity's solvency.

It is very striking that, at the moment of their collapse, Kids Company seems to have had a very serious problem with cashflow, at the least. In the week that began on Monday 27 July, the trustees were seeking £6m in donations - including £3m from the government - to enable it to lay off large numbers of its staff and shrink to a much-reduced version of its former self. Were it not for the arrival of that £3m state grant on Thursday 30 July, staff may not have got paid for the last month.

During that week, the trustees may have made a judgment that they had a problem with cashflow, but given enough time, they could pay all their bills - so were still solvent. According to Mr Yentob's account of events, news of the police investigation - which emerged on the Thursday of that critical week - changed the trustees' view about the solvency of the charity and so they decided to turn away a major donor and give up the fight.

Given the long-term fall in their private fundraising though, the basis for their judgement about the solvency of the charity prior to that event ought to be paid close attention - not least given the disruption to the lives of staff and clients caused by Kids Company's very sudden stop.

- Published5 August 2015

- Published7 August 2015