Cedric Belfrage, the WW2 spy Britain was embarrassed to pursue

- Published

Britain failed to prosecute a member of the intelligence services who passed secrets to Russia in World War Two because it feared being embarrassed over what might come out in court, files in the National Archives have revealed.

MI5 also appeared to have failed to grasp the significance of former film critic Cedric Belfrage's activities.

The Briton worked for an arm of MI6 in New York after a career in Hollywood.

But his colleagues were unaware he had become increasingly left wing, probably after a trip to the Soviet Union.

Historians say his espionage could be ranked alongside that conducted by members of the Cambridge spy ring during the Cold War.

'Well known'

In November 1945, Elizabeth Bentley contacted the FBI and said she had been part of a Soviet spy ring operating in the US.

When the FBI approached those alleged to be involved, the only person to initially offer a partial confession was Belfrage.

Born in London in 1904, he studied at Cambridge University, but left before taking his finals. He was based in Hollywood in the 1920s, then became the film and theatre critic for the Daily and Sunday Express, before moving back to the US in the 1930s.

By 1941 Belfrage was working for British Security Co-ordination (BSC) in New York, which co-operated with the FBI and where he had access to secret information.

Other security service files released by the National Archives...

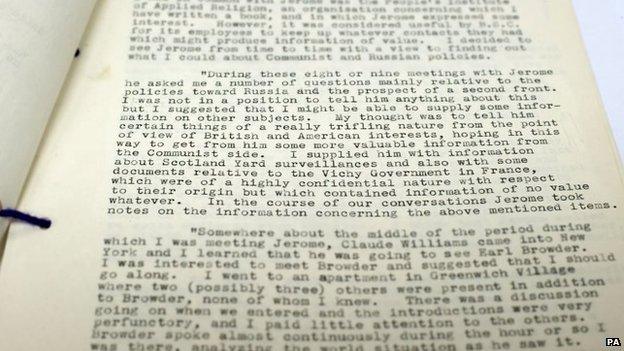

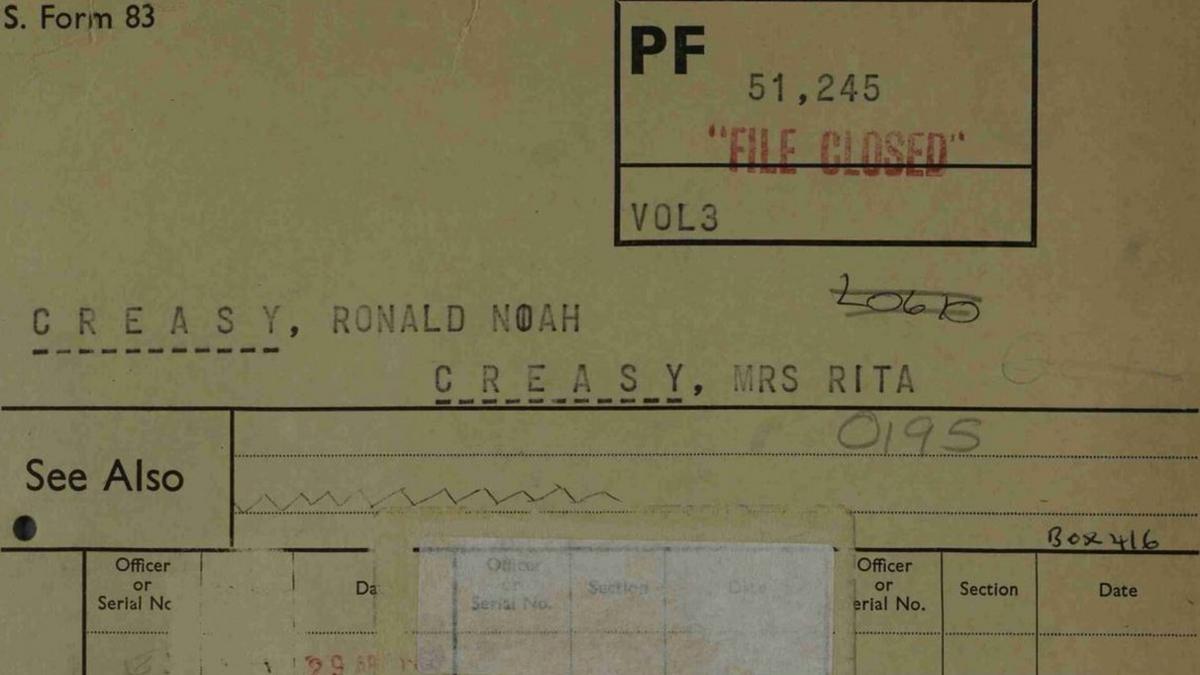

This file from the National Archives shows Cedric Belfrage admitting spying for the Russians in WWII

During his time at BSC he was introduced by American communists to top Russian spy Jacob Golos. And between 1941 and 1943, Belfrage - codenamed "Benjamin" by the Russians - passed on secret documents on subjects including British policy on Russia and the Middle East, reports on France and from British police.

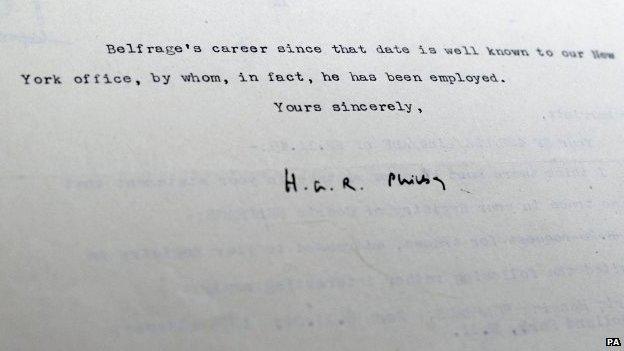

The revelation worked its way back to MI6. An officer wrote back to MI5 saying "Belfrage's career since that date is well known to our New York office, by whom, in fact, he has been employed".

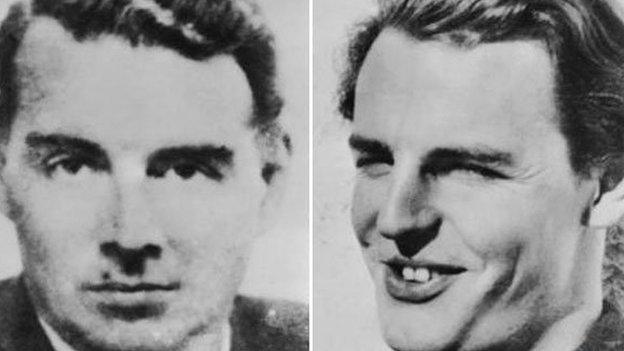

What is remarkable is the MI6 officer who wrote those lines was Kim Philby, himself a Soviet spy, and one of the Cambridge ring recruited at university in the 1930s.

It seems almost inevitable Philby would have told his Russian handlers of the US revelations including about Belfrage. This, in turn, may have allowed Belfrage to plan his response.

Anti-communist fervour

Belfrage had not broken any US laws because he had passed on British secrets.

But in 1953 he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee - part of the McCarthy hearings into communism in America. Belfrage refused to answer questions, prompting the committee to suggest he should be deported.

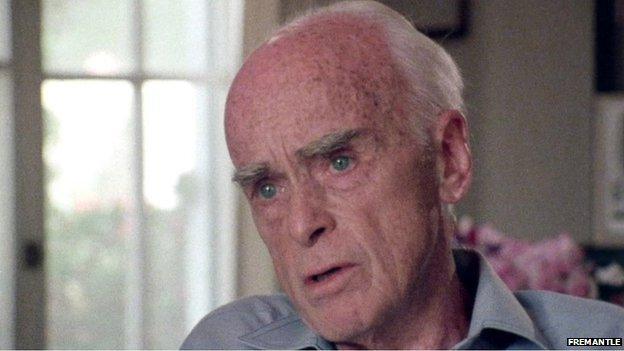

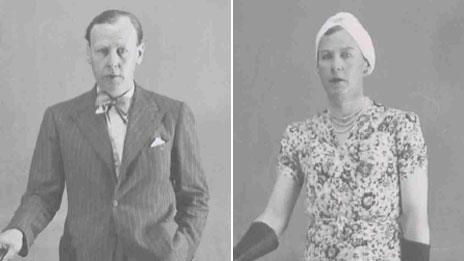

Professor Christopher Andrew: "Soviet intelligence in the middle of the second world war actually ranked (Belfrage) ahead of Philby"

He was detained in 1955 and deported. The grounds were not espionage but that he had been a member of the American Communist Party in the 1930s under a false name.

All this attracted considerable attention in the UK press and Parliament where some lauded Belfrage for standing up to the anti-communist fervour sweeping the US.

His return to the UK left MI5 with a headache. They had seen evidence he had been spying and some wanted him prosecuted.

Belfrage, however, had offered a defence in his secret partial confession to the FBI.

He had admitted passing files to Russian contacts during WW2 but claimed this was on the orders of his superiors in British intelligence in order to get material in return.

"My thought was to tell him certain things of a really trifling nature from the point of view of British and American interest, hoping in this way to get from him some more valuable information from the Communist side," said Belfrage, according to the files.

MI5 thought they could show the documents he handed over were of real value but knew they would need more evidence to rebut his defence in court.

This led to a request to MI6 to see if they could help - but it could not find any files or people who could disprove his defence. The files also make reference to the potential embarrassment of a prosecution in which Belfrage's role in British intelligence would come out in court.

And there was concern over public opinion which in some quarters supported him.

'Important spy'

Belfrage was not prosecuted but was put under extensive surveillance when he returned to the UK. A few years later he moved to Latin America, where he died in 1990.

There is a further element to the story. The declassified National Archives files reveal MI5 was not able to establish much about his activities and never interrogated him.

Yet historians say other evidence points to Belfrage having been an important spy for the Soviets.

This document on Belfrage's activities was signed by Kim Philby

Prof Christopher Andrew, who has acted as official historian for MI5 and examined secrets taken from the KGB archive, said: "Soviet intelligence in the middle of World War Two actually ranked him ahead of Philby - only for a year or two, but nonetheless, it was an important year or two."

He says this was partly because Philby was mistrusted as a double agent and as Belfrage held an important position at the junction between Britain and the US.

"I think he was one of the most important spies the Soviet Union ever had," agrees Svetlana Lokhova, an expert on Russian intelligence.

The Soviets would have been desperate for intelligence on British and US policies at a key moment in WW2, she said.

She highlights decrypted communications mentioning Belfrage and the fact he was run directly by Jacob Golos. The Russians made repeated attempts to reconnect with him after their spy died.

Ms Lokhova and Prof Andrew both say the fact the KGB has never revealed anything about Belfrage suggests he was important.

But concerns over embarrassment and the failure of MI6 to unearth evidence for a prosecution meant he appears to have been a spy who got away.

More on this story in The Hollywood Spy on The Report on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 BST on Thursday, 17 September.

- Published21 August 2015

- Published21 August 2015

- Published17 September 2014

- Published7 July 2014

- Published23 May 2013

- Published18 November 2013