The man who is being deradicalised

- Published

A controversial and secretive government deradicalisation programme called Channel targets people considered at risk of being drawn into violent extremism. For the first time one man agreed to tell us what actually happens on the programme.

Perched on the edge of a boxing ring at a youth centre in East London, Hanif Qadir jokes with Adam - not his real name - and scolds him for being a pain as a father might a naughty son. But this relationship is more complex.

Adam, 28, a Polish Muslim convert, says he had been preparing to train as a jihadi fighter in Tunisia and hoped to end up in Syria. There are currently an estimated 700 UK citizens who have travelled to Syria or Iraq to support or fight for jihadist organisations.

"I was thinking I've got nothing to lose and I have a lot to win. If I die, if they shoot me or anything, I'm not going to lose anything except my life," he explains to the Victoria Derbyshire programme.

He has been spending the past nine months with Mr Qadir, a youth worker who is trying to steer him away from radical thinking.

'Re-education'

Adam is on the government's secretive Channel programme, part of the Prevent agenda, which is aimed at stopping people being drawn into violent extremism. Prevent has been a controversial part of the UK's counter-terrorism work since its launch following the attacks on the London transport network on 7 July 2005.

Because of its sensitive nature, details of people who are on the programme are a tightly-guarded secret and what actually happens to them is barely known to anyone outside those involved.

Watch Catrin Nye's film in full here, external

Mr Qadir knows what it's like - in 2002 he travelled to Afghanistan to fight for al-Qaeda, but quickly returned. He admits he was also radicalised and manipulated, but now works with the government to stop others taking a similar path.

Adam's been going through a sustained a period of "re-education" and what Mr Qadir described as "making him vulnerable to our mentoring".

He explains: "It wasn't about changing his mind. It was about allowing him to critically analyse what he thought and what the reality is. So I would take him through the teachings of Islam and show him this is what the Prophet, peace upon him, has said about extremism."

Hanif Qadir says Adam was "easily manipulated"

Mr Qadir admits it has not been an easy process and "frustrating at times", with Adam arguing back to much of his tutoring.

Adam was sleeping rough when he was found by a youth outreach team, after coming to the UK to look for a job. He was taken to the Active Change Foundation in Walthamstow - a brightly-coloured youth centre full of pool tables and video games.

The centre was set up for local youths by Mr Qadir when he got back from Afghanistan. Anyone can use it but it also receives government funding and describes itself as a place "where messages of hatred and violence can be challenged".

Problem case

Adam was quickly identified as potentially "on the edge" after alarming some people at the centre with his support for Islamist violence.

When he went on to strongly support the gunmen responsible for the murders at the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris, group leader Hanif Qadir said he knew he had a problem case.

They discovered Adam had a complex background. He had become estranged from his family and ended up in France, where he says he was told about the war in Syria by a group of Muslims with extreme views. They showed him live headcam footage from other fighters there. They convinced him that no-one in the world was helping the Syrians, and he should.

"I was watching what is going in with the world and I see all the people, they like - they do nothing about it, do you understand?" he says.

More from the BBC on tackling extremism

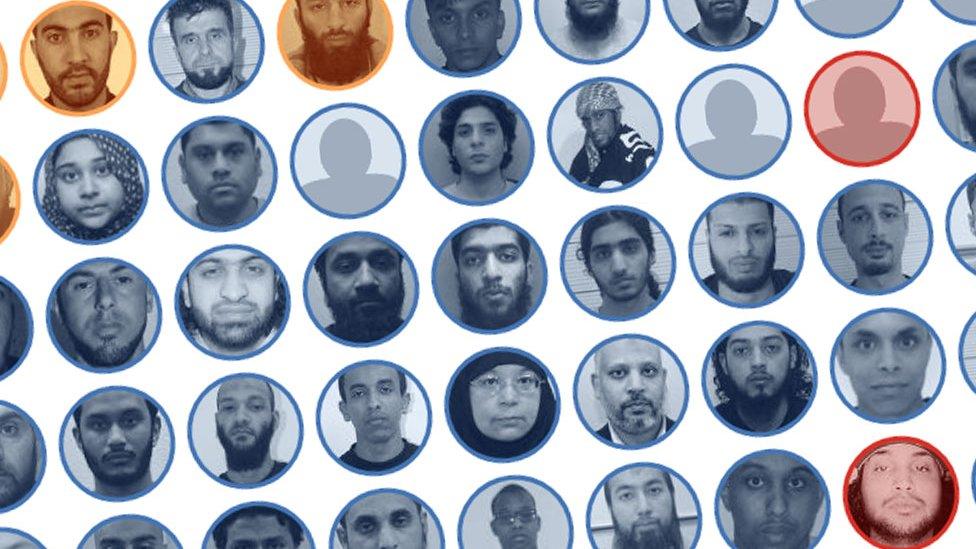

Who are Britain's jihadis? The BBC's database with the stories of more than 100 people who have died, been convicted of offences relating to the conflict in Syria or Iraq or are still in the region.

Is the government's Prevent strategy failing? Analysis from BBC security correspondent Frank Gardner.

BBC home affairs correspondent Dominic Casciani on why the Prevent strategy is so controversial.

Mr Qadir says he believes these people were linked to the Charlie Hebdo killers and "to some networks within Syria and Iraq".

"Intentionally he's not a terrorist," he explains. But "he was prepared to do something nasty. I've realised how easy it was for somebody to manipulate him".

After finding Adam, Mr Qadir approached the local authority and explained he felt Adam would benefit from being part of the programme. A panel meeting was organised which included the police and other statutory service providers like the local mental health trust and education services. A bespoke intervention was then designed to fit his needs.

Adam explains that he had converted to Islam in 2010 and before meeting Mr Qadir he had been "learning" about Islam.

"But the books which I received, I didn't know they were extremist, you know? They were not saying directly kill the people or things like that because the book is very nice writing you know - in beautiful language. But it's just the way the book makes you feel after you read."

The people who end up on the Channel programme have been identified as potentially on a path to violent extremism. In all, more than 4,000 people have been referred since it started in 2006.

But those figures obscure its recent growth - in 2006-07 only five people were referred, by 2009-10 this had increased to 467. In 2013-14, this had more than doubled to 1,281, figures from the National Police Chiefs' Council show.

Of the total number of those referred, 20% were assessed as needing support through the Channel process.

Threat

Mr Qadir says he also knows many people, Muslims in particular, do not approve of his work. Because Prevent requires schools and universities to look out for signs of extremism it is seen by some as a spying programme.

Mr Qadir disagrees. "Don't get me wrong, we've had parents who are very suspicious of why are their children looked upon by the police or by the local authorities as suspicious? Is it because they're Muslim?

"But then the child's been taken through the process and admitted to the parents that they could have been in Syria. These parents don't understand the reality of the threat to their children and to our communities."

It is notoriously difficult to measure success in this kind of terrorism prevention work. And although Channel has been internally evaluated the results have never been made public.

I asked Adam if he felt he had been "deradicalised".

"I am in the process. Sometimes the information I was studying in the books, they come in back to my head. I'm fighting with this and it's going in a good direction," he says.

Mr Qadir is more emphatic. He thinks without his intervention "he'd have probably gone abroad and either been killed or killed others".

This interview was part of a series of reports by Catrin Nye about radicals and what British authorities do with those considered to hold these views. You can watch the reports on Victoria Derbyshire on weekdays from 09:15-11:00 BST on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel.

- Published12 October 2017

- Published6 March 2015

- Published26 August 2014