Extremism plan 'could backfire' warns watchdog

- Published

- comments

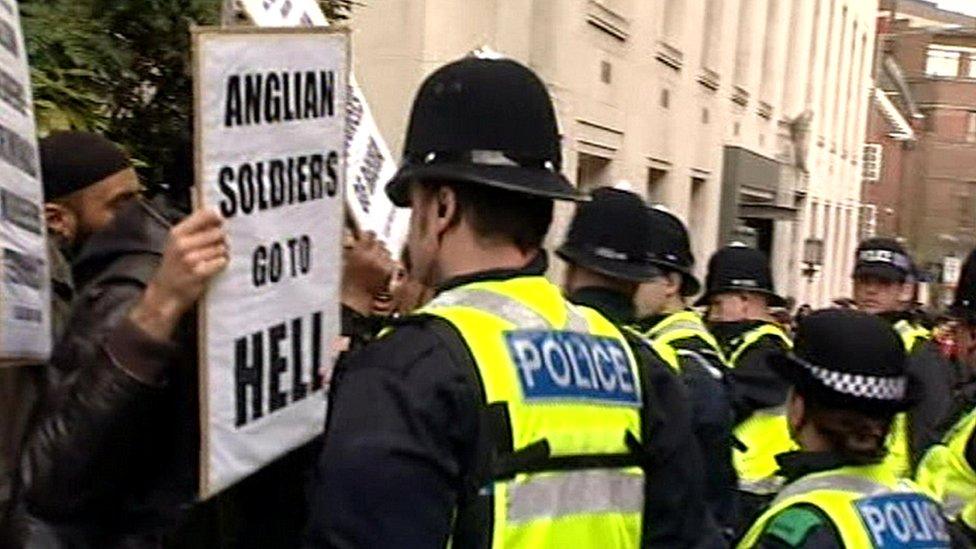

The new laws are expected to include powers to ban extremist organisations

Plans to ban extremism could spark a backlash in Muslim communities, the terrorism laws watchdog has warned.

Legislation reviewer David Anderson QC said poorly-drafted laws could play into the hands of terrorism recruiters.

Ministers are planning new powers to curb the activities of people whose actions fall short of terrorism.

They are likely to include banning extremist ideologues and preachers and those involved in radical groups linked to Islamist causes.

Mr Anderson's warning came shortly after the head of MI5 gave his first live interview to the BBC in which he set out the case for new powers to intercept internet communications.

The prime minister is also chairing a meeting of the government's extremism taskforce amid opposition from the National Union of Students to new duties upon universities to monitor extremism.

In his annual report on the workings of terrorism legislation, Mr Anderson, the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, said that while it was "right and proper" that the government should have a counter-extremism strategy, it could go wrong if forthcoming proposals were not carefully thought through.

Three of its key measures are expected to be:

Powers to ban extremist organisations

An Extremism Disruption Order to restrict the activities of specific individuals

Closure orders to shut down premises used as part of extremism

Mr Anderson said he had identified 15 issues that the government had to address in Parliament if the proposed legislation was going to work - including a clear and intelligible definition of extremism, define the causal link between extremism and terrorism and how the laws could affect the police's relationship with communities.

He said: "These issues matter because they concern the scope of UK discrimination, hate speech and public order laws, the limits that the state may place of some of our most basic freedoms, the proper limits of surveillance, and the acceptability of imposing suppressive measures without the protections of the criminal law.

"If the wrong decisions are taken, the new law risks provoking a backlash in affected communities, hardening perceptions of an illiberal or Islamophobic approach, alienating those whose integration into British society is already fragile and playing into the hands of those who, by peddling a grievance agenda, seek to drive people further towards extremism and terrorism."

Mr Anderson warned that while the plan's supporters would argue that the counter-extremism powers would only be aimed at specific targets, that did not address the dangers of "overbroad laws" to inadvertently affect others.

"If it becomes a function of the state to identify which individuals are engaged in, or exposed to, a broad range of "extremist activity", it will become legitimate for the state to scrutinise (and the citizen to inform upon) the exercise of core democratic freedoms by large numbers of law-abiding people," he said.

"The benefits claimed for the new law - assuming that they can be clearly identified - will have to be weighed with the utmost care against the potential consequences, in terms of both inhibiting those freedoms and alienating those people."