Migrant crisis: What awaits refugees coming to the UK?

- Published

- comments

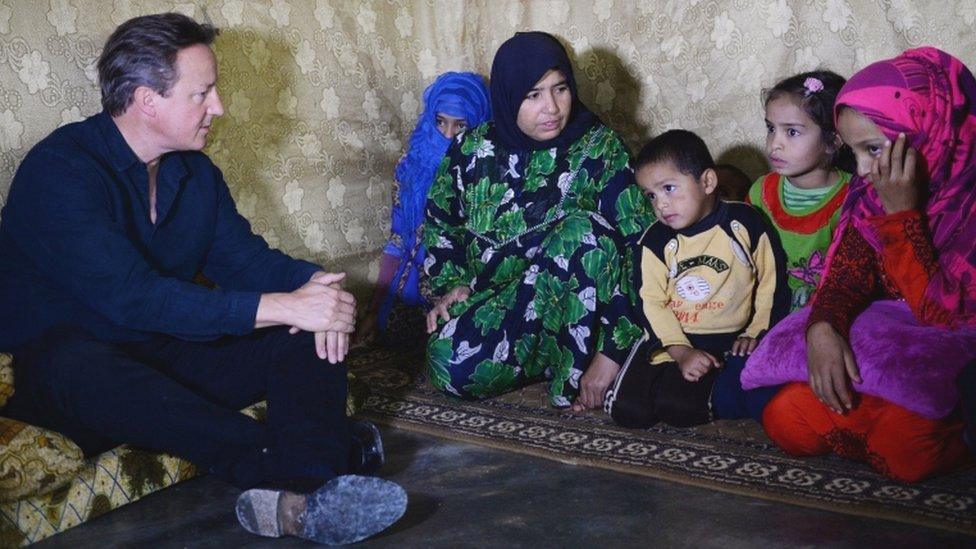

The UK will take 20,000 Syrian refuges from camps by 2020

The first Syrian refugees to be resettled in the UK since the government announced it was expanding its protection scheme have arrived - but how does their adopted country help them integrate successfully?

We don't know who they are or where they have been settled - and it's not even clear if they were already due to arrive prior to the prime minister's announcement that the UK would take 20,000 by 2020.

Since 2014, more than 200 Syrians have come to the UK under the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement (VPR) scheme., external More than 2,200 more have arrived by their own accord in the last year, claiming asylum at ports.

The VPR is modelled on the decade-old Gateway Protection Programme which the government uses to settle about 750 refugees a year from all around the world. And its core principle is need, rather than numbers.

Every step

The UK asks the UN's refugee agency (UNHCR) to identify people whom it wants to resettle away from camps because of one or more of the following factors:

They need specialist medical care that they cannot get locally.

They are women and children at risk of further harm if they are not moved.

They are survivors of violence and torture who need specialist support to rebuild their lives.

The process of moving to the UK can take months.

UN officials draw up lists of candidates - quite literally biographical spreadsheets that detail their lives, injuries and complex needs - and a Home Office team sits around the table with their counterparts from other agencies to work out which ones the UK can help.

Once someone has been identified and approved, they have full legal rights to settle in the UK for five years - and for the first months, they will be accompanied every step of the way into their new life. They are not given refugee status - which would mean automatic and permanent right to settle.

When they arrive in the UK, they are met at the airport by a welcome team who take them to their new home. And the next morning, their personalised integration plan begins.

Just like anyone else, they can work and claim benefits. Everything about life in the UK is explained to them in briefings and classes.

Syrian refugees in the UK

20,000

more refugees will be resettled in the UK by 2020

4,980

Syrian asylum seekers have been allowed to stay since 2011

-

25,771 people applied for asylum in the UK in the year to end June 2015

-

2,204 were from Syria

-

87% of Syrian requests for asylum were granted

-

145 Syrian asylum seekers have been removed from the UK since 2011

School places are ready for their children, there is a GP already set up to take them on and, where necessary, specialists to work on their long-term health problems.

There are trips to the job centre and colleges for those ready to go back to work or study.

Maurice Wren, chief executive of the Refugee Council, says that, at its best, the Gateway scheme has turned around lives because incoming people have been able to get the support they need to start again.

"They have stability from the first week," he says. "Life is made as easy as possible for them so they can rebuild.

"Gateway has had an amazing effect in sensitising agencies to what they need to do to resettle refugees. And people take advantage of the golden opportunity that is given to them."

Who pays?

An incredible success story? Well partly - but there are real challenges behind the scenes.

The UN wants the UK to take Syrians from the camps who have very complex health problems caused by the war.

The BBC has learned basic details about the lives of some of those who have made it onto the provisional UN list for future settlement in the UK.

Housing associations are organising crash courses on life in the UK for some new arrivals

It includes individuals who have been paralysed by appalling injuries, rape victims, people who have survived gas attacks and shrapnel blasts.

These aren't people who can be put up in someone's spare room. In many cases they will need adapted homes and potentially full-time nursing care.

And this is where care and resettlement clashes with the brutal reality: who pays?

The Home Office is only funding the first year of settlement - meaning that local authorities and other agencies could be left with bills for years to come at a time when they are going to be under immense pressure to cut their budgets.

The Vulnerable Persons Relocation Scheme

All of the "paperwork" is done before the refugees arrive. From day one they get housing, have access to medical care and education and they can work

Refugees are granted five years' humanitarian protection, external which includes access to public funds, the labour market and the possibility of family reunion, external, if a person was split up from their partner or child when leaving their country

After those five years they can apply to settle in the UK, external

The scheme will be funded for the first 12 months by the government

David Simmonds, who chairs the Local Government Association's migrants task force, said: "There needs to be a proper plan. What happens after the first year? What happens at the end of five years?"

He says that if the arrivals are badly-handled over the next four years - particularly as councils make major cuts in spending elsewhere - there could be tensions in some communities.

"If someone has been on a housing waiting list for years, and then they see someone else getting in first - it won't feel fair and people will kick back against that.

"But the more we are able to plan - and the more people can see what has been planned - the easier it can be."

Treated differently

The challenges don't end there.

Many local authorities already complain to central government that they are struggling to handle existing asylum seekers and those given refugee status.

And that's because those who apply in the country, rather than through one of the UN schemes, are treated differently.

Abdul Aziz and Suha say they feel welcome in the UK

Councils say that they're often picking up some of the costs relating to the asylum system, particularly around children, even if the housing is paid for directly by the Home Office.

At the same time, new refugees who are not part of Gateway or VPR don't get any help with integration because the government scrapped a special advice programme for them in 2011.

Over the four years it operated, more than 12,000 former asylum seekers were helped to move on after becoming legally-recognised refugees.

Today, critics say, many are ending up homeless because nobody is helping them to restart their life once they have legal status.

In other words, while two groups of refugees are getting comprehensive resettlement support because they came in under the UN banner, another group is getting very little at all.

- Published22 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015

- Published6 September 2015