From Syria to Bradford: A refugee family's tale

- Published

The Al Ahmed family have settled in Bradford after being forced from their home in Syria to live in Lebanon

Last week it was revealed that almost half the Syrian refugees who have resettled in the UK have been housed in one area of Bradford.

Of the 216 refugees given sanctuary so far under the government's Vulnerable Persons Relocation Scheme 106 have been resettled by one organisation - the Horton Housing Association, based in Little Horton.

BBC Look North communities reporter Sabbiyah Pervez was born and raised in Little Horton as the daughter of Pakistani immigrants and has been back to her childhood home to meet one Syrian family who represent the newest incomers to the area.

She visited the Al Ahmed family - Walid Al Ahmed, his wife Esaf and their daughters, four-year-old Hala, eight-year-old Rashal and 14-year-old Rasha.

Mr Ahmed tells me he is from Idlib in north western Syria, he had a chicken farm back home but when the war started four years ago he began commuting from Idlib to Lebanon until he eventually moved his family there.

During this time he was diagnosed with cancer. Treatment in Lebanon was too expensive so his only option was to travel back to Syria for his medical appointments.

"I was between two deaths, if the cancer didn't kill me then I expected to die travelling for my treatment," he said.

"I would say my goodbye to my family, in case I didn't return."

Mr Al Ahmed said the devastation and intensity of the war was worse each time he visited. "I would see dead bodies on either side of the road, just lying there. It put my own life into perspective, my cancer was nothing to what these people had endured."

Despite surgery, he was told his cancer had spread, so he travelled back to Syria for check-ups, only to find the hospital had disappeared. It had been bulldozed to the ground.

As his condition deteriorated, he applied for help from the United Nations and after six months arrived in the UK through the Vulnerable Persons Relocation Scheme, external on medical grounds.

The Al Ahmed family left Idlib in north west Syria four years ago as the fighting intensified

He has received treatment for his cancer in Britain and is grateful and relieved to be here, happy that his children have a chance to grow up without the fear of bombs and gunfire. But he also feels guilty about those he left behind.

"Syria used to have a very high education rate, but what now for the young children and orphans who have grown up with war? I wish I could help those children also."

Mrs Al Ahmed tells me many Syrian children are orphans, their parents having been killed by "death barrels" - barrel bombs used by President Assad's regime, dropped from aircraft.

Mr Assad denies Syrian government forces have been using barrel bombs.

Mrs Al Ahmed tells me the story of her relatives whose house was destroyed. The parents were killed but their two children survived. She says the eldest is still suffering from trauma, he asks constantly "Where is my mother?" She looks away, tears stream down her face.

From what they tell me nobody is safe. Even those who do not engage in political dissent are detained, depending on the mood of the checkpoint guards you are either allowed to cross through the province or you are arrested and tortured.

I ask them if they have any happy memories of Syria. Mrs Al Ahmed begins by telling me about her childhood - her father grew olive trees and had a vineyard at the front of the house.

After his death they would eat the olives and grapes in his memory. She stops, the tears return. "They bulldozed our house, destroyed the trees and destroyed the graveyard, we have no memories left."

I ask the daughters how they feel to be here in Bradford. The eldest, Rasha, says she is happy, but when I ask her what she remembers of Syria, she starts to cry. She cannot speak through her tears.

She was 10 when they first left Syria, the house she grew up in has been destroyed, the field she played in with her friends is gone.

Eight-year-old Rashal interrupts; she tells me she was sad, but is now very happy to be here. She loves her new school and her friends.

Now she attends the same primary school I did as a little girl. She is a confident bright girl who appears to have adapted well to the move.

Mr Al Ahmed tells me he doesn't watch the news in front of the children, it is too upsetting for them. He says that when they first moved from Syria to Lebanon, Rasha could only remember the tanks and gunfire.

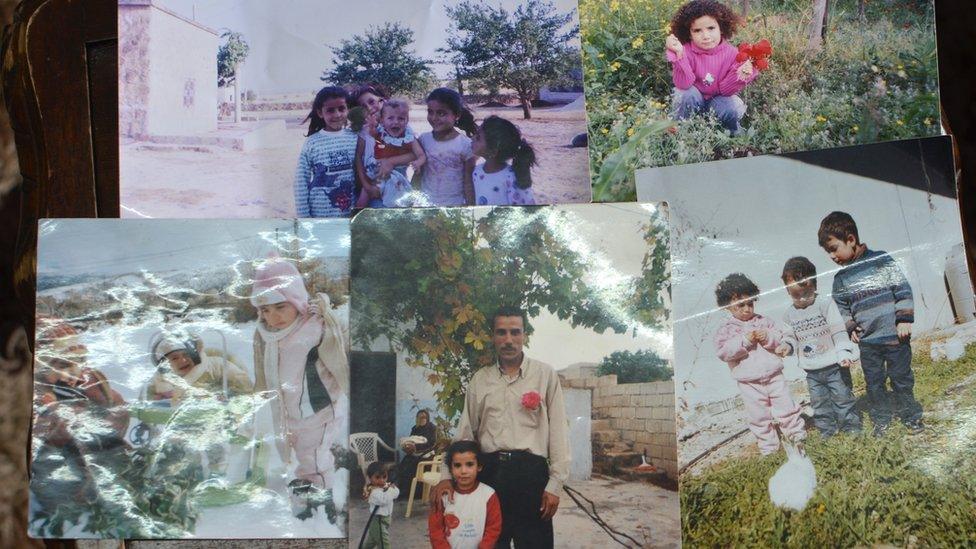

Family photographs are a poignant reminder of their past life in Syria before the war

Before I leave, I ask one final question. If there is one thing you want the public to know what would you tell them?

Mr Al Ahmed pauses for a moment, then begins: "The Syrian people are incredibly entrepreneurial, we are used to building out of nothing, we have learnt to depend on ourselves.

"We are hardworking and resilient, when Syrians come here they will not come to sponge off the benefits, they will want to work and contribute to a society that has given them a home."

He then refers to the stories in the media suggesting there are radicals among the refugees. "We are a people fleeing war, we have seen war and devastation, all we want is peace, Syrians will not flee war to create war," he says.

"If people do not want refugees in their countries then we need an end to the war. If there is peace there would be no need for people to flee."

As I leave they thank me for telling their story. I get back into my car and drive to Horton Park, a nearby public garden I would visit frequently as a young girl.

As I look around it strikes me that this park and the streets surrounding it are dear to me, each corner holds a memory. I remember when I left Bradford for a few years to study and start my family, each time I returned it was a sweet homecoming, I would slot back into place even if I had been absent for months. But it was the people and the places that made it so.

Would it be the same if there was nothing or nobody to return to? Would it be the same if I couldn't point out my primary school to my daughter, or show her the house I was brought up in, or the place where we would always play hide and seek?

- Published14 September 2015

- Published9 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015

- Published4 September 2015