Tackling extremism is no easy task

- Published

Blair and May have both made fighting extremism a priority

"Let no-one be in any doubt, the rules of the game are changing."

"The game is up."

Two politicians from different parties, 10 years apart, delivering a similar message to extremists.

The first statement was from Tony Blair, the second from Theresa May.

Mr Blair's remarks in August 2005 came in response to two sets of terrorist attacks in London in a fortnight: the suicide bomb blasts of 7 July, external, which killed 52 people, and the failed copycat bombings of 21 July, external.

Amid concerns about foreign-born terrorists in Britain, the then Labour prime minister said he was signalling a "new approach" to deportation in which people who fostered hatred, advocated violence to further a person's beliefs, or justified such violence, would be liable to exclusion or removal.

It was all part of Mr Blair's 12-point plan, external to tackle the "fanatical fringe" of extremists that was at risk of tarnishing the "good reputation of the mainstream Muslim community".

New approach

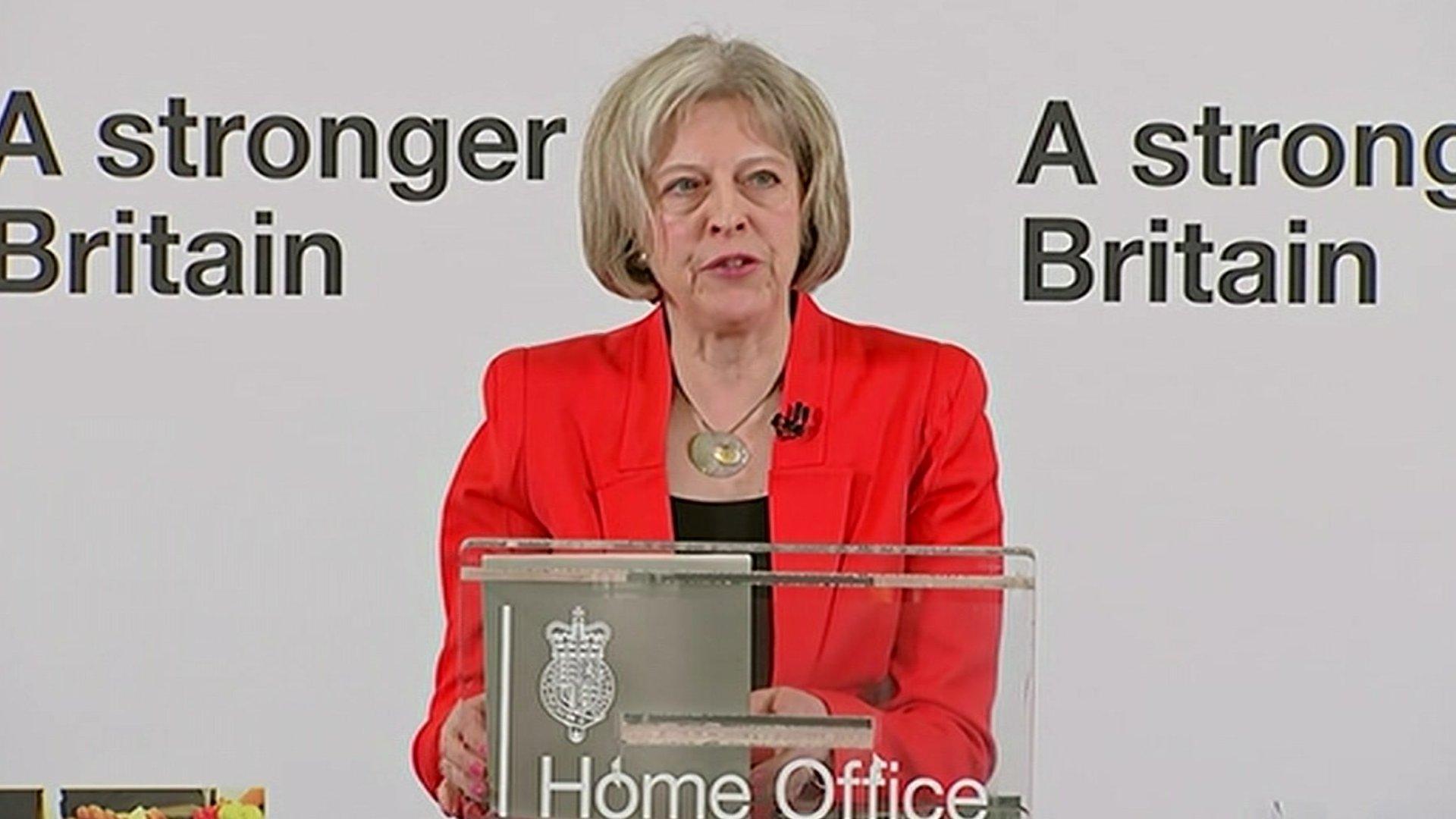

In March 2015, Theresa May, the Conservative home secretary who was then in coalition, presaged another "new approach" to extremism, external.

In this case it had been sparked by a series of attacks by so-called Islamic State in Europe and elsewhere, the departure from the UK of 700 people to fight or support jihadists in Syria, and the continuing "severe" threat from terrorism in Britain.

Theresa May: "Islamist extremism is the most serious and widespread form of extremism"

Mrs May called for a "partnership" of people to empower those who wanted to "celebrate" British values and "defeat ignorance".

"This partnership will reclaim the debate from extremists," she said, warning them: "We will no longer tolerate your behaviour."

One of Mrs May's suggestions, "closure orders", external, giving police and councils powers to shut premises used to support extremism, is remarkably similar to Mr Blair's proposal (subsequently abandoned) to close places of worship, including mosques, used as a "centre for fomenting extremism".

The former PM advocated wider grounds for the "proscription", or banning, of extremist organisations - again, not too dissimilar to the current home secretary's call for "banning orders" for such groups.

And both Tony Blair in 2005 and Theresa May in 2015 emphasised the importance of the "values" that sustain the British way of life, "tolerance" in particular.

But whereas those values weren't spelled out by Mr Blair, forming only the background to his radical proposals (which included longer pre-charge detention), they are absolutely central to Mrs May's plans, which are being developed into a Counter-extremism Bill.

Battle of ideas

The home secretary, together with David Cameron, is fighting a battle of ideas in which anyone who actively opposes democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths is considered to be an extremist.

There are fears a heavy-handed approach could be counter-productive

Writing earlier this year, my colleague Dominic Casciani set out the difficulties of such a definition.

Since then, David Anderson, the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, has cautioned that the approach could be counter-productive.

In his annual report, external, published in September, Mr Anderson said there were "dangers" in creating laws that were too broad.

"If it becomes a function of the state to identify which individuals are engaged in, or exposed to, a broad range of 'extremist activity', it will become legitimate for the state to scrutinise (and the citizen to inform upon) the exercise of core democratic freedoms by large numbers of law-abiding people," he wrote.

"If the wrong decisions are taken, the new law risks provoking a backlash in affected communities, hardening perceptions of an illiberal or Islamophobic approach, alienating those whose integration into British society is already fragile and playing into the hands of those who, by peddling a grievance agenda, seek to drive people further towards extremism and terrorism."

Broadcast vetting

Another measure expected in the bill is a commitment to strengthen the role of Ofcom, the broadcasting regulator.

In May, the Guardian said ministers had considered giving Ofcom the power to vet programmes, external before transmission to prevent extremist material being broadcast.

Sajid Javid expressed concerns that Ofcom was being turned into a censor

The newspaper published a letter, written two months earlier, from Sajid Javid, Culture Secretary at the time, in which he expressed concerns, external that allowing Ofcom to take "pre-emptive" action would turn the organisation into a "censor".

It's unclear what's become of that exact proposal after it got short shrift from Mr Javid, but bolstering Ofcom's powers remains on the agenda.

The Queen's Speech briefing document, external spoke of "tough measures" against channels that air extremist content and David Cameron has said, external he wants to target "foreign channels that broadcast hate preachers".

Main elements of the Counter-extremism Bill:

Banning orders: a new power for the home secretary to ban extremist groups.

Extremism disruption orders: a new power for law enforcement to stop individuals engaging in extremist behaviour.

Closure orders: a new power for law enforcement and local authorities to close down premises used to support extremism.

Broadcasting: strengthening Ofcom's roles so that tough measures can be taken against channels that broadcast extremist content.

Employment checks: enabling employers to check whether an individual is an extremist and bar them from working with children.

Source: Queen's Speech briefing document.

IRA ban

The prospect of such restrictions on the media has evoked memories of the ban on broadcasting the voices of members of organisations in Northern Ireland, external believed to support terrorism.

The ban, in force between 1988 and 1994, affected 11 loyalist and republican groups, though Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA, was the main target.

Sinn Fein's Martin McGuinness was affected by the broadcast ban

"This law feels like Margaret Thatcher's attempt to starve the IRA of the oxygen of publicity in the '80s," says Chris Phillips, a security consultant and former detective who headed the National Counter Terrorism Security Office.

Having spent most of his lifetime in law enforcement, Mr Phillips is no shrinking violet - he supports the principles underlying the Bill and believes most people will too - but he's worried about how it will work in practice with police facing further budget cuts.

"It could prove difficult to police with dwindling resources," he says.

"Every case is likely to get media coverage and be expensive to prosecute.

"The key will be how they define 'extreme' and at what level they set the prosecution bar".

As ministers put the finishing touches to the Counter-extremism Bill, they'll be well aware about the importance of definitions and guidance for prosecutors in making the measures work.

But they might also want to consult the history books.

Television and radio programmes found ways to get round the broadcasting ban; if anything, they felt under even more pressure to reflect all shades of opinion in Northern Ireland.

As for Tony Blair's 12-point plan to counter extremism and terrorism, some proposals were brought in but the group Hizb Ut-Tahrir has never been banned, despite his pledge to do so.

Control orders, whose use Mr Blair promised to expand, have since been scrapped, while 90-day detention without charge for terrorism suspects never made it on to the statute books but instead ignited a furious row over civil liberties that smouldered for five years.

The government can ill afford that.

- Published11 June 2015

- Published11 June 2015

- Published23 March 2015