Can ministers define extremism?

- Published

- comments

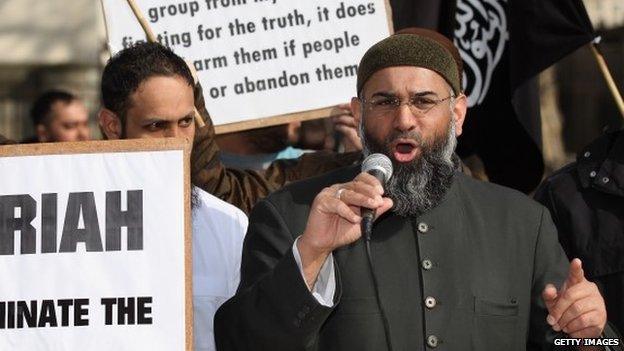

Will Islamist political activist Anjem Choudary soon lose his microphone?

In 1964, Justice Potter Stewart of the US Supreme Court famously gave up looking for a legal definition of pornography and declared, "I know it when I see it."

Will the British government's plan to define extremism face the same problem?

That's just one of the unanswered questions from the prime minister and home secretary's plan to make a counter-extremism bill a central piece of the new government's programme.

The proposed policies were first floated last year - but didn't make it into law because the coalition partners couldn't agree on them.

Top of the list are banning orders for extremist organisations that seek to undermine British democracy, but fall short of the legal test to be outlawed under terrorism legislation.

Second, ministers want to create extremism disruption orders, which would be used to restrict the activities of people they believe are grooming and radicalising young people.

We've no idea yet how they will work in practice, but they might operate a bit like anti-social behaviour orders which have to pass various tests before a court.

Hate crimes

The government also wants powers to close premises used by extremists - that's something that has been floated time and again since Tony Blair was prime minister.

And finally, there will be a raft of powers designed to stop extremists entering the UK, abusing charitable status or the airwaves.

Hate crimes and terrorism are easy to define in clear terms because they both involve the intention to cause some kind of harm to another. But can you define extremism?

Home Secretary Theresa May says her definition of extremism is "limited and practical"

The home secretary gave her definition earlier this year.

"Some say we cannot base a counter-extremism strategy on British values because it is too difficult to define them," she said. "But we are not calling for a flag to be flown from every building, or demanding that everyone drinks Yorkshire Tea and watches Coronation Street.

"Our definition of extremism is 'the vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs'.

"And we regard calls for the death of members of our armed forces as extremist behaviour. This is a limited, practical and inclusive definition - and I challenge anybody to say it is unreasonable."

On the other hand, critics say that's a totally subjective test, which will simply attack free and open debate.

Definitions are going to be really important because if Parliament does not give the courts a clear explanation of what is and what is not extremism, the various banning orders could result in an endless loop of legal challenges relating to human rights and freedom of speech.

If you want the home secretary's answer on where the line lies, listen to her BBC Radio Four interview this morning - it's not yet clear.

Legal issues aside, this package is part of a shift in focus.

The UK has a massive toolkit of counter-terrorism laws already in place, including recently created orders to temporarily ban some British suspects from returning home.

The proposed new tools are part of an extended strategy to "disrupt" extremists enough to create opportunities to bring vulnerable people back from the edge of becoming a danger to society.

Policing thought?

But there are also practical questions.

First, could such bans work without tying up the resources of the security services or leading to accusations of a "police state"?

Greater Manchester police chief Sir Peter Fahy has expressed concern about "policing thought"

MI5, for instance, already has triage-like systems to prioritise watching the most dangerous people - it can't monitor everyone with dangerous views.

What's already clear is that some chief constables don't want to be in the game of policing thought, external.

Undercover police have long monitored domestic extremism, but the allegations of historical wrongdoing by Scotland Yard, including watching some MPs, has led the home secretary to order an inquiry.

Second, could bans be enforced?

Margaret Thatcher's broadcasting ban against Sinn Fein didn't work. And today, as fast as social media companies take down accounts run by supporters of the self-styled Islamic State, they pop up again in a different guise, as my BBC World Service documentary series explains.

So in the internet age, can any government really hope to silence the extremists unless it's got a plan to defeat their ideas?

- Published13 May 2015

- Published30 September 2014