Shaker Aamer: What happens now?

- Published

As the jet carrying Shaker Aamer landed at Biggin Hill airport, the questions over his future were only just beginning.

Whatever your perspective or personal views of what Mr Aamer is, was, or represents, his return to the UK was greeted with a collective sigh of relief across Whitehall.

The 5,017 days of detention were not only a real point of tension in the critical transatlantic relationship; they also soured and compromised attempts by the government to reach out to some of the hardest-to-reach Muslim communities.

In the short term, he will begin to receive expert medical help, including a psychiatric assessment. He will finally get to meet the son who was born on the day he arrived at Guantanamo Bay.

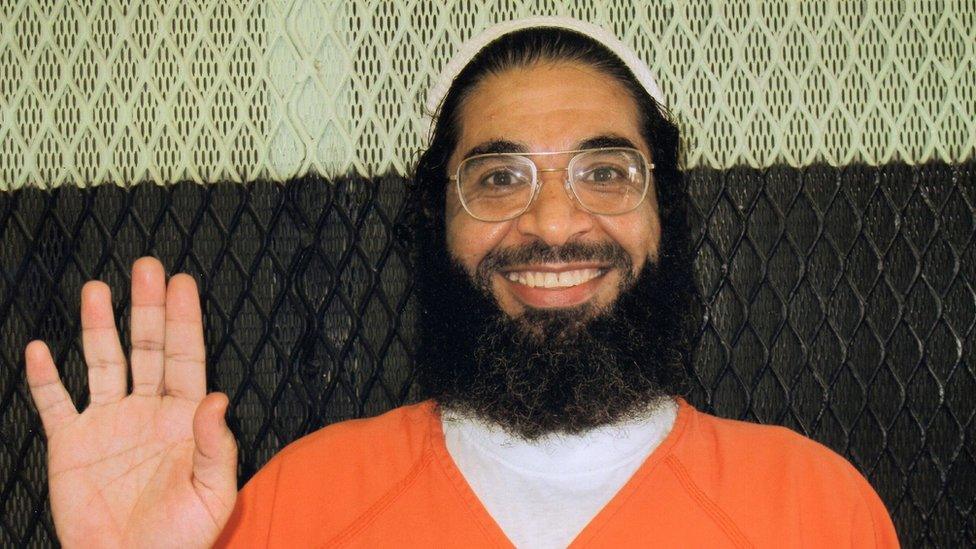

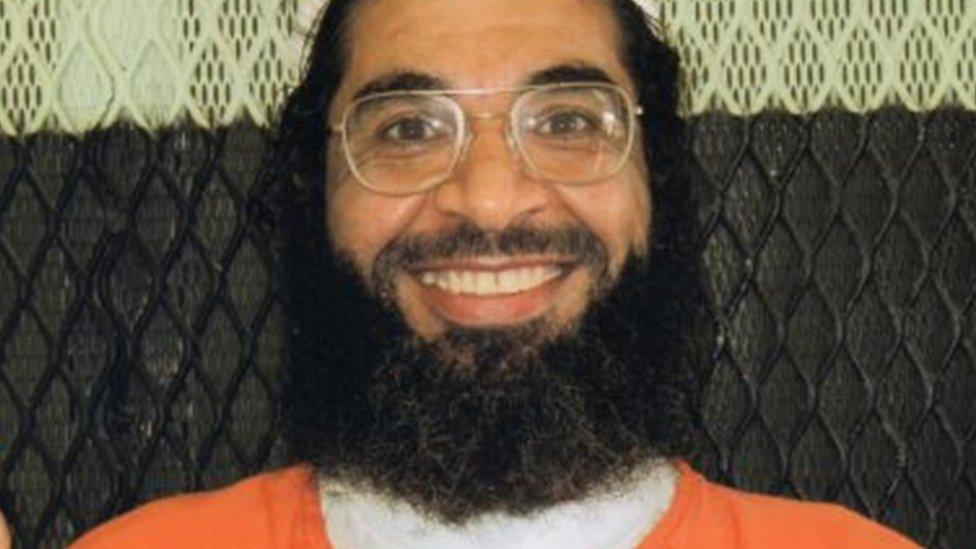

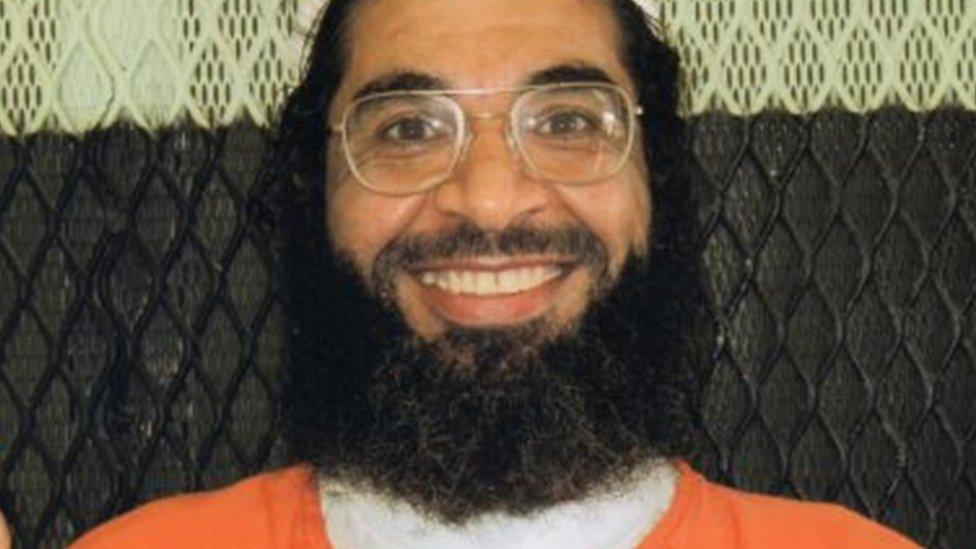

Mr Aamer was detained at Guantanamo for 13 years

But for some, Mr Aamer's return represents a risk. Davis Lewin, of the Henry Jackson Society, a security and foreign relations think tank, has urged the UK to think very carefully about how it manages and monitors him now he is back.

Mr Aamer's legal team have said he will submit to whatever monitoring is required - although they also argue it is unnecessary because the case against him comes from unreliable allegations extracted during torture.

If MI5 decides to monitor him, he may never know for sure that it is happening - such is the nature of that kind of work.

Moral compass

There are bigger questions for the UK, questions of legacy and lessons to be learnt.

Critics argue that in the wake of 9/11 the US was not the only country to lose its legal map and moral compass.

London didn't seem to want to tell Washington that Guantanamo was a bad idea - and it didn't insist that any British men detained in Afghanistan be brought back to the UK.

That, say critics, was a dereliction of long-standing British principles of justice.

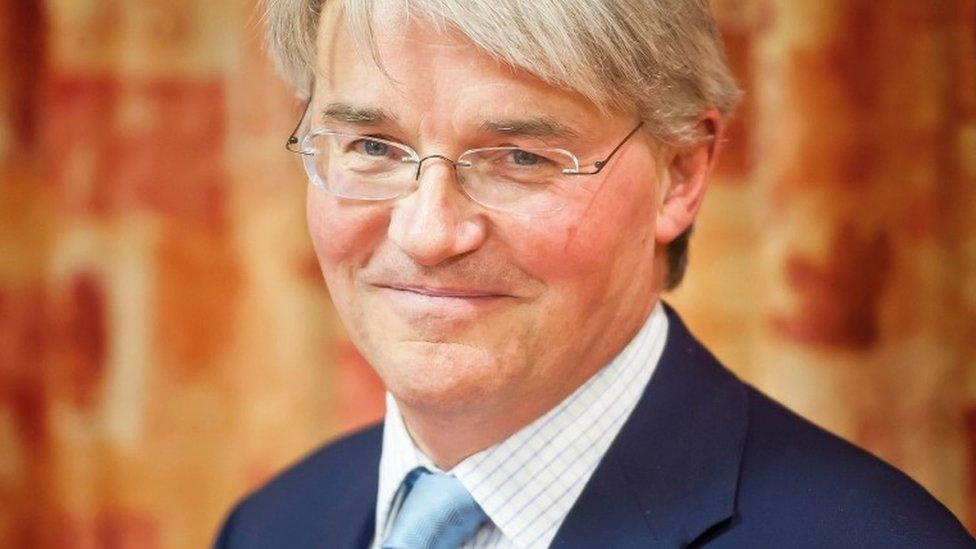

Former cabinet minister Andrew Mitchell is one of the critics of Mr Aamer's detention

"Human rights and justice and the rule of law are for everybody," says former Conservative cabinet minister Andrew Mitchell, a member of the cross-party group that lobbied Washington to release Mr Aamer.

"He has been denied that. Not only is that terrible for him, but we have to be better than that if we're going to defeat the scourge of terror and terrorism.

"We're going to have to rise above these things and stick to the rule of law, and accept that human rights belong to everyone."

Some American interrogations involved intelligence material provided by Britain - and that could amount to complicity in torture.

And so, many MPs are now pushing for real answers to questions about Britain's role in the weeks and months after 9/11.

"One of the things that it is absolutely essential that happens in due course is that [Shaker Aamer] looks the camera in the eye in Britain and says what happened to him," says Mr Mitchell.

"If as is alleged he was tortured, and if there was any UK involvement in that, we need to get to the bottom of that not only because it's utterly wrong if it was done in our name, but also because we need to ensure that these sort of circumstances don't happen to anyone else."

Complicated road

But why haven't those answers come out yet?

The government fought a mammoth legal battle to prevent courts disclosing the full extent of what ministers and officials knew about the transfer of men to Guantanamo.

But the claimants ultimately accepted a multi-million pound settlement - meaning the government never had to disclose what happened.

Parliament then passed the Justice and Security Act which allows ministers to apply to hear cases in secret - closing that door for good.

Campaigners still hoped the facts would emerge in a full judge-led inquiry into complicity in rendition.

The promised inquiry was shelved because there is still the possibility of criminal charges in relation to alleged rendition to Libya.

So it is now down to the Intelligence and Security Committee to investigate.

Earlier this week, the committee's new chair, Dominic Grieve QC, said he wanted to get started.

The last detainee with a UK connection now has a long and complicated road ahead of him. He has to learn how to stop being Detainee 239 of Guantanamo Bay and become Shaker Aamer, father of four, of south-west London.

His legal team say he does not want to persecute those who abused him - and in a recent letter to the BBC he talked about the "contract" he believes he must honour with the British people for their support.

- Published30 October 2015

- Published25 September 2015

- Published30 October 2015