Defence review to identify new threats and spending priorities

- Published

The number of regular troops is being cut from 102,000 in 2010 to 82,000 in 2020

Military chiefs, civil servants and politicians are not always ready or equipped to fight the battles in front of them, let alone the wars of the future.

Think of Iraq and Afghanistan - their crystal ball is often as muddy as yours or mine.

While the 2010 Strategic Defence & Security Review (SDSR) did identify terrorism and international military crises as high level (tier 1) threats, there was no specific mention of Russia and so-called Islamic State (IS) did not exist in anything like its present form.

The 2015 SDSR will identify both IS and Russia as tier 1 threats, but they may not be the same threat five years hence.

They say that armies train to fight the last war they fought and military plans don't survive the first contact with the enemy.

"In 2010 it was rather assumed the armed forces would get out of Afghanistan and take a bit of a breather," says Michael Clarke, director of the defence think tank Rusi.

Instead "the world has shown us the armed forces won't be getting a holiday," he says.

Genuinely strategic?

First, the government should be commended on its commitment to carry out a defence review every five years. Before, defence reviews were done ad hoc.

But ministers will still have to overcome a high degree of scepticism as to whether this latest SDSR is genuinely "strategic" or if it matches Britain's global ambitions with the resources needed.

SDSR 2010 may have been strategic in name but it'll be remembered for the savage cuts that followed.

It wasn't just the scrapping of iconic names, it left gaping holes in Britain's defences - with no aircraft carriers for the Royal Navy and no maritime patrol aircraft to hunt down Russian submarines.

Strategic Defence & Security Review: What happened last time

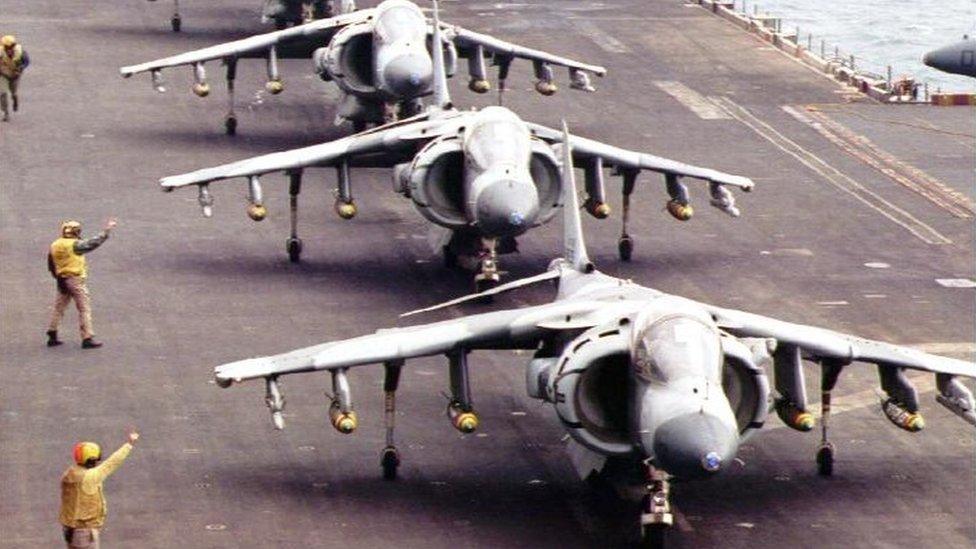

Harrier jump jets were a casualty of the 2010 review

David Cameron announced that Harrier jump jets, the Navy's flagship HMS Ark Royal and planned Nimrod spy planes were to be axed

42,000 MoD and armed forces jobs were to go by 2015

The RAF and Navy were to lose 5,000 jobs each, the Army 7,000 and the MoD 25,000 civilian staff

Overall, defence spending was to fall by 8% over four years

Mr Cameron denied it was a cost-cutting exercise and said the UK had to be "more thoughtful, more strategic and more co-ordinated in the way we advance our interests and protect our national security"

The Royal Navy also lost thousands of personnel and is now having to recruit marine engineers from foreign navies.

In order to man its two new aircraft carriers it'll need another 2,000 sailors but they'll have to manage with fewer, which could mean mothballing other warships.

The armed forces are still licking the wounds inflicted by the 2010 review.

Defence Secretary Michael Fallon admits it involved "painful" decisions. But this week he told me: "We're now able to expand the defence budget again... to enhance the capabilities of our armed forces to deal with the increased threats we face."

Key to this, he says, has been the commitment to meet the Nato target of spending 2% of the nation's wealth (GDP) on defence.

It means there'll be a modest increase in the defence budget over the next five years.

Submarine hunting

Mr Clarke says while the armed forces might be in a better place this time round "it'll still find it difficult to meet all the commitments the government wants it to meet".

New maritime patrol aircraft will be top of the shopping list. Over the past five years Britain has had to call on the help of the US, Canada and France to hunt for suspected Russian submarines near UK waters.

RAF crews have already been training on the US Boeing P8 Poseidon - but it's expensive. Other defence contractors are offering cheaper alternatives. Britain needs new aircraft now, but it has to work out what it can afford.

The RAF will also be looking for more frontline fast-jet squadrons. It now has seven squadrons but would like more than a dozen.

In the fight against IS it's still having to rely on the ageing Tornado.

The life of some of the early Typhoons is likely to be extended to add a few more squadrons, but still probably fewer than the RAF would like.

Defence spending will meet Nato's target of being 2% of GDP, the government says.

One key decision will be how many of the new F-35s Britain will buy. The aircraft, also known as the Joint Strike Fighter, is already the most expensive defence project ever undertaken by the Pentagon.

The UK had originally planned to buy 138, but each jet will cost about £100m.

The decision on F-35s is also important for the Royal Navy and its two new aircraft carriers from which they will fly, as are new anti-submarine frigates needed to protect the carriers.

The Navy wants 13 of the new Type 26 frigate. If it has to settle for less that would have a knock-on effect on shipbuilding jobs on the Clyde.

The government will also signal its push to renew the fleet of Vanguard submarines which carry the Trident nuclear systems. The cost of building four new submarines will be updated from around £20bn to more than £30bn.

The Army will be looking at how many new armoured "scout" vehicles they'll be getting and new Apache attack helicopters. Although the Army has become less likely to engage in any large-scale conflict on its own, it still needs a range of capabilities to deploy alongside its key ally - the US.

The Army also hopes this SDSR will help change public perceptions - that it's not just there to deploy en masse. The Army now sends small teams to trouble spots all over the world to help train and assist fragile states with conflict prevention.

The British Army's 2020 plan

Some regiments will be merged; others face "salami-slicing"

The number of regular troops is shrinking, from 163,000 in 1978 to 102,000 in 2010 and 82,000 in 2020

The government has said it does not want whole regiments to be scrapped; some will be merged, others face "salami slicing".

The Army will become more reliant on part-time soldiers; the number of reservists will double from 15,000 to 30,000 by 2020

The government says Britain will have an effective, well-equipped fighting force, integrating regulars and reserves

Analysts say the Army will have resources for only one major operation at a time and there will be swingeing cuts to support units such as logistics and engineers

In fact, this SDSR will signal a significant break with the past. Mr Clarke says: "What we are seeing is a shift of resources away from fighting major wars towards using the forces in more intelligence-led, cyber-led, Special Forces-led ways for specific operations."

The armed forces still want and need their big ticket items like warplanes and warships, but recent events have underlined the shift.

In the wake of the Paris attacks, ministers have said the security services will get another 1,900 personnel while there'll be an extra £1.9bn for cybersecurity and another £2bn for Special Forces.

The RAF will see the size of its drone fleet double to 20.

It's a sign the military will be involved in more intelligence-led counter-terrorism operations and an indication that, post-Iraq and Afghanistan, politicians are increasingly reluctant to put "boots on the ground".

After the brutal cuts of the last SDSR, ministers hope this one will be a positive story. While the Ministry of Defence is still having to make efficiency savings, it's not being asked to make cuts right across the board like many other government departments.

But more important than how the review is regarded by the public, or the armed forces themselves, is how it's interpreted by Britain's allies and enemies.

- Published1 October 2015

- Published19 October 2010

- Published18 October 2010