Are UK bombs making a difference in Syria?

- Published

RAF Tornados bombed the Omar oil fields on the night of the Commons vote

It is now a month since MPs voted in support of UK military action against the group known as Islamic State (IS) in Syria.

On the same night that parliament gave its approval RAF Tornados launched their first air strikes on the Omar oil fields.

Newly despatched Typhoon jets joined in the attacks two nights later, followed by a third set of strikes on the same oil fields on 6 December.

And then? It appears hardly anything. There has only been one other British air strike in Syria - an unmanned Reaper drone firing a Hellfire missile at an IS checkpoint near Raqqa on Christmas Day.

Despite the vote, the focus of British military action has continued to be on Iraq. The RAF's much lauded brimstone missile has not yet even been fired over Syria.

The prime minister's claim that the RAF would make a "meaningful difference", external there has yet to be borne out.

So far more than 90% of the air strikes inside Syria have been conducted by the US.

It is of course still early days. But given the limited number of UK air strikes it begs the questions: why was the government so keen to expand the air strikes to Syria, and why the agonising over a vote that appears to have changed relatively little?

UK air strikes have targeted the Omar oil fields in eastern Syria

It is worth recalling that David Cameron argued for Britain to join the Syria air strikes.

He said it was to deny IS, also known as Isil, a safe haven, external. "It is in Syria, in Raqqa, that Isil has its headquarters, and it is from Raqqa that some of the main threats against this country are planned and orchestrated," he said.

He argued that by authorising British air strikes over Syria, the RAF would be able to take out the "snake's head" - the leadership of IS.

Iraq priority

So why hasn't that happened? The first reason is that Syria has not been the military priority.

In Iraq air strikes are making a difference, largely because there is an army to work with on the ground.

Ramadi has been the target of both US and UK air strikes

The recapture of most of Ramadi, external has been achieved with the help of the RAF. On 18 December it carried out its most sustained bombing campaign over Ramadi and near Mosul, external - with 22 air strikes over a 24-hour period.

And there are more reasons as to why Iraq, not Syria, will continue to be the focus of the bombing campaign.

Iraq's prime minister has now said his forces will be turning their attention to Mosul.

Even though the tide appears to be turning in Iraq, the country will still be heavily reliant on Western air power for months, possibly years to come.

The fight against IS in Iraq will be hard. But in Syria it will be even tougher.

There is still no ground force around which the US-led coalition can rally.

Before the parliamentary vote, David Cameron admitted the situation on the ground in Syria was "complex".

But his assertion that there were about 70,000 Syrian opposition fighters, who did not belong to extremists groups, still seems fanciful.

Day-by-day the so-called "moderate rebels" are being targeted by Russian aircraft determined to bolster President Assad's position.

Surveillance key

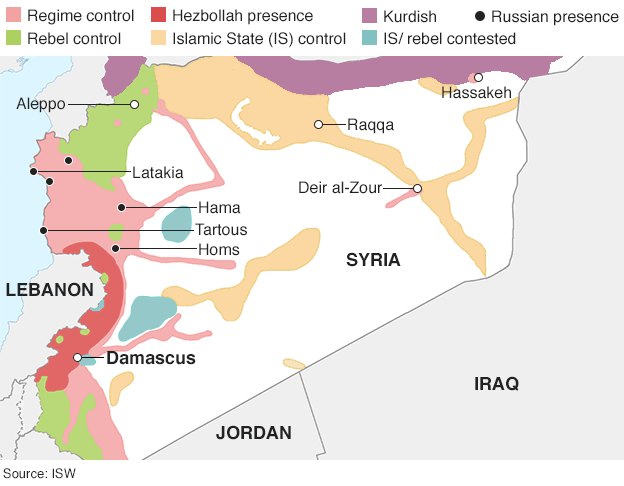

The battle lines in Syria are blurred and constantly shifting. And it is much harder to conduct an air campaign without eyes on the ground.

However, it would be wrong to give the impression that Syria is being completely ignored.

Six Typhoons were deployed to RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus after the UK approved air strikes in Syria

On 19 December the US-led coalition carried out its largest ever pre-planned attack on oil installations near Raqqa, dropping 140 bombs and missiles in a single day (in the coalition daily update this was listed as just one air strike as it involved one target).

The US has also been going after senior figures: 10 so-called "high-value targets" have been killed over the past month alone.

The coalition spokesman, US Colonel Steve Warren, said: "We are striking at the head of this snake, but we haven't severed it yet, and it's still got fangs.", external

The US has been flying combat missions over Syria for more than a year now.

It has had more than 100 aircraft gathering intelligence and finding targets (it is costing the US $11m - £7.4m - a day to fight this war).

This might, in part, explain why the RAF has carried out relatively few air strikes against the "head of the snake" in Syria. It often requires weeks, even months, of surveillance.

But Britain's very limited involvement in Syria, along with its limited number of aircraft, still raises questions and doubts.

Is the UK really making a "meaningful difference"? Or was the vote on 2 December as much to do with politics as military effect?

What is going on in Syria?

Who’s fighting whom in Syria? Explained in 90 seconds

Syria has been embroiled in a bloody armed conflict for nearly five years. More than 250,000 Syrians have been killed, and 11 million made homeless.

What started as pro-democracy Arab Spring protests in 2011 spiralled into a civil war between President Bashar al-Assad's government forces and opposition supporters.

In the chaos, jihadist group IS moved in over the border from Iraq and claimed territory. The US, Russia, France and other world powers have entered the fray, adding to an already complex web.