What Alexander Litvinenko report means for UK-Russia relations

- Published

There were suspicions in Whitehall that Litvinenko's death was a "political assassination"

When it comes to dealing with President Putin's Russia, the UK government has long been faced with a dilemma: How far should Russia be treated as a threat? And how far could it be an opportunity?

Ever since Alexander Litvinenko's murder a decade ago, relations have zig-zagged.

First, Gordon Brown's government acted tough, in 2007 expelling Russian diplomats, limiting visas for Russian officials and virtually ending co-operation between intelligence services.

Ostensibly this was to punish Russia for failing to co-operate over the Litvinenko murder investigation.

But the harshness of the measures seemed to reflect a belief, or at least suspicion, in Whitehall that the Russian state security services were probably involved in what amounted to a political assassination on the streets of Britain, using a dangerous radioactive substance.

But that open hostility changed after David Cameron took over in 2010.

Reeling from the cavernous debt served on Britain by the 2008 financial crisis, his coalition government placed a higher premium on looking for trade opportunities abroad to increase the nation's profits.

So he sought to repair relations with the Kremlin.

He even travelled to Russia to hold talks with President Putin, and made him his personal guest when the Russian leader came to London to watch his country's athletes competing in the 2012 London Olympics.

British diplomats indicated that while deep disagreements with Moscow over the Litvinenko affair still cast a shadow, the dispute had been "parked" in order not to interfere with other bilateral relations. A Russian-British year of culture was planned for 2014

But the warm-up did not last.

Ukraine tensions

In 2014 the Ukraine crisis erupted.

President Putin abruptly annexed the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea, declaring it was historically Russian territory.

Not only Britain but all Western powers reacted with alarm at what looked like a flagrant disregard for Ukraine's sovereignty and a challenge to European security.

That dismay deepened when President Putin followed up the annexation by declaring he reserved the right to intervene to protect Russians everywhere.

This included eastern Ukraine, which he said had "mistakenly" been made part of the fledgling Soviet Republic of Ukraine after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

David Cameron and Vladimir Putin shook hands at the G20 summit in Turkey in November in what looked like a display of collaboration

Before long, open warfare had broken out between Ukrainian troops and local rebels there, who were apparently armed and reinforced by Russian special forces. Moscow has always denied any direct military involvement.

In response David Cameron spoke up strongly. He was among the most vocal of European leaders calling for tough EU sanctions against Russia.

Soon a deep freeze in UK relations with Russia was back, this time reinforced by European-wide and US economic and financial sanctions.

The rhetoric hardened: British and other Western governments began to talk of Putin's Russia as a serious threat to their security.

And meanwhile Russia began to blame the US and its allies for seeking to fuel insurrection against Russia, both in neighbouring countries like Ukraine, and inside Russia itself through "fifth columnists", whose criticism of their own country, the Kremlin said, amounted to a betrayal of Russian national interests.

At this point, it became clear that the Litvinenko affair was no longer being "parked" by the UK government.

It was announced there would, after all, be a public inquiry into the circumstances of Alexander Litvinenko's death.

But even as the process of a public investigation into the Litvinenko murder unfolded, the diplomatic mood music changed again.

'Grudging recognition'

Once again, other events intervened, and the hostile rhetoric on both sides was tempered by a new pragmatism on the part of the West, and a new economic anxiety on the part of Russia.

As a result, over the last 12 months there has once again been a gradual shift in Western capitals away from seeing Vladimir Putin as only a menace towards a grudging recognition that, while he should not be trusted, he should not be entirely ostracised either, because Russia's role in global diplomacy seems to be too important.

There has been a "grudging recognition" of the Kremlin's role in global diplomacy among Western powers

The first consideration was with regard to Ukraine.

Early in 2015 the Russian president suddenly agreed to join a peace process to try to end the conflict in Eastern Ukraine - the so-called "Minsk process".

Since then, this has proceeded slowly.

Both Kiev and its Western backers remain highly suspicious of Russian intentions.

But the Minsk process in itself is an acknowledgement that in the end the Ukraine crisis will have to be solved politically, and that can only be done if Russia is at the table.

Syria and Iran

The second consideration was Russia's largely positive role when it came to the negotiations over Iran's nuclear activities.

Russia worked closely with the US and European powers to secure the deal.

Consistently Western diplomats insisted that Russia had played a helpful part, not least in providing a home for the bulk of Iran's enriched uranium, a vital element of the implementation deal which allowed most nuclear sanctions against Iran finally to be lifted.

And the third and most important consideration concerned the Syria conflict.

As migrants flooded into Europe, and as new horrific terrorist attacks hit Paris and other capitals, this became for the West an ever more urgent crisis in need of a solution.

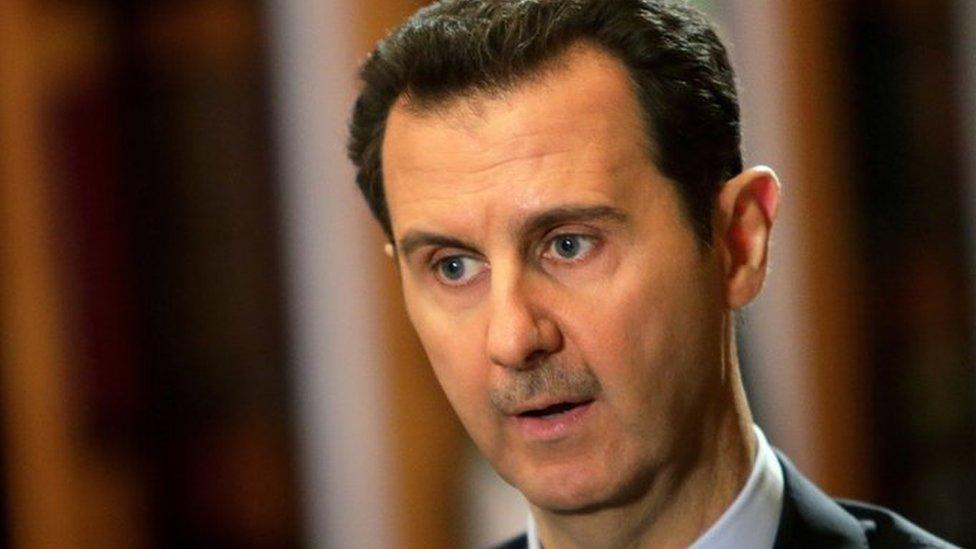

Western powers were taken aback when Russia supported Syrian president Bashar al-Assad's forces

When President Putin abruptly switched military tack last autumn away from Ukraine in order to enter the war in Syria to support President Assad's forces, Western powers were taken aback.

They remained wary of Russia, but also interested in seeing whether it could be persuaded to play a positive role over the Syrian diplomacy, to persuade the Assad regime to agree to a compromise which might in time end the fighting, and to stop attacking anti-government rebels and focus their firepower on the more important enemy - Islamic State jihadists.

In the wake of the publication of the Litvinenko report, both David Cameron and his home secretary made clear they were acutely aware of Russia's Janus-like status.

"We will continue to engage guardedly with Russia where needed to secure our national interest," said Theresa May.

"We totally disapprove of what they're doing in Syria, in terms of bombing the moderate opposition; that is making the situation worse, not better," said Mr Cameron, adding: " We have put sanctions in place, led the arguments in Europe for sanctions against Russia, because of their illegal action in the Ukraine.

"But do we, at some level, have to go on having some sort of relationship with them because we need a solution to the Syria crisis? Yes we do. But we do it with clear eyes and a very cold heart."

Decision for UK

Less than six months ago, the British prime minister and Russian president were shaking hands at the latest G20 summit in Turkey, an outward display of what looked like cordial collaboration.

In the wake of the report, there is now a new chilliness - the latest zig-zag. And it may get worse.

Britain has hinted it may be considering further measures. Moscow has already warned it would retaliate and this would further poison bilateral relations.

But what the British government now has to decide is how far to keep channels open to Mr Putin, while at the same time sending him a signal that he should not think he can get away with anything, especially when it appears to involve criminal acts on British soil.

- Published21 January 2016

- Published21 January 2016

- Published21 January 2016

- Published21 January 2016

- Published21 January 2016

- Published21 January 2016

- Published21 January 2016

- Published31 July 2015

- Published21 January 2016