What next for Julian Assange?

- Published

A UN panel has concluded that Wikileaks founder Julian Assange has been "arbitrarily detained" by UK and Swedish authorities since his arrest in 2010. What does it mean for him and how did it come about?

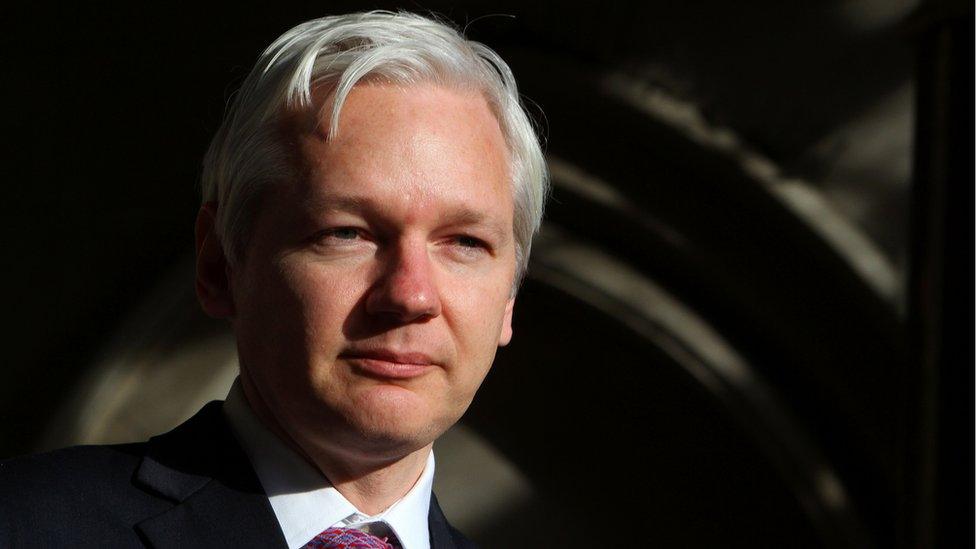

Who is he?

Julian Assange, a 44-year-old Australian with an exceptional ability to crack computer codes, set up Wikileaks - which publishes confidential documents and images - in 2006.

He first made headlines around the world in April 2010 when the website released footage showing US soldiers shooting dead 18 civilians from a helicopter in Iraq. His supporters see him as a valiant campaigner for truth, but to his critics, he is a publicity seeker who has endangered lives by putting a mass of sensitive information into the public domain.

What's happened so far?

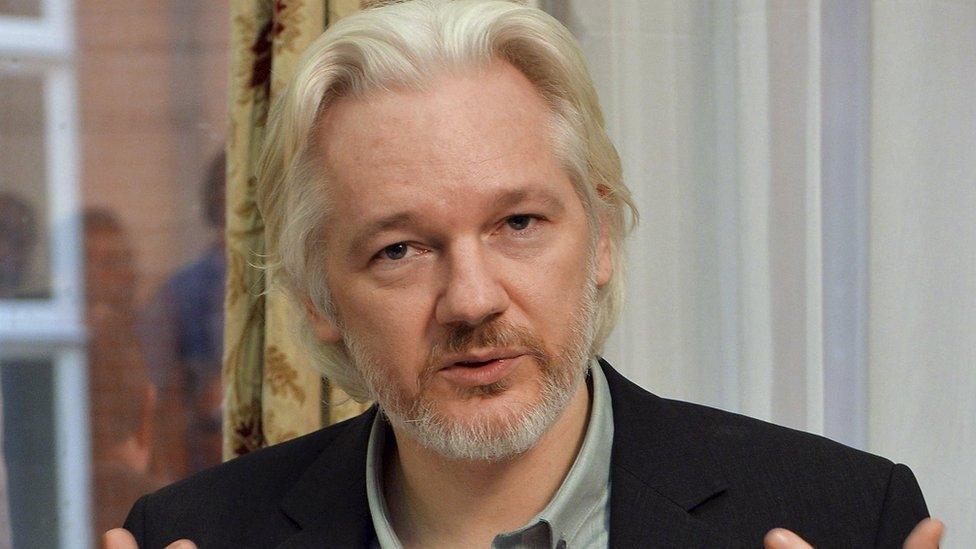

In 2012, Mr Assange took refuge in London's Ecuadorean embassy to avoid extradition to Sweden over sexual assault claims, which he denies. He claimed asylum there after the UK Supreme Court ruled the extradition against him could go ahead - and has been there ever since.

Why is he in the embassy?

If he steps out of the embassy, he will likely be arrested. A warrant for his arrest is still in place in the UK. Mr Assange fears that if he goes to Sweden, he will be sent to the US to answer charges of espionage relating to Wikileaks' publication of secret US documents.

Why did the UN panel get involved?

In 2014, Mr Assange complained to the panel, saying he was being "arbitrarily detained" as he could not leave without being arrested. He argued that living in 30 square metres of the embassy with no sunlight or fresh air had taken a "significant toll" on his mental health.

Who is on the panel?

The UN's Working Group on Arbitrary Detention - to give it its full title - is made up of five legal experts from around the world. Established in 1991, it has made hundreds of rulings on whether imprisonment or detention is lawful, which have helped to influence governments to release people.

High profile complainants include Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian, who was released in Iran last month, former pro-democracy President Mohamed Nasheed, released in the Maldives last year, and Myanmar party leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

Previous rulings by the panel have gone against countries with some of the world's worst human rights records, including Saudi Arabia, Myanmar and Egypt. The decision against Sweden and Britain in favour of Mr Assange is likely to be controversial.

What has it ruled?

The panel, which investigates whether states are in compliance with human-rights obligations, has ruled that Mr Assange's case amounts to "arbitrary detention".

He was subjected to different forms of deprivation of liberty - initial detention in Wandsworth Prison in London, followed by house arrest and confinement at the Ecuadorian embassy - it said.

It also found "a lack of diligence" by the Swedish Prosecutor's Office's investigations resulted in his lengthy loss of liberty.

The detention violated his human, civil and political rights, the panel said. It called for Mr Assange's detention to be brought to an end, and for him to be given compensation.

What are its powers?

The panel does not have any formal influence over the British or Swedish authorities. The UK Foreign Office said Mr Assange had voluntarily avoided lawful detention and it still had an obligation to extradite him.

Before the ruling, Mr Assange said he would expect the immediate return of his passport and the termination of further attempts to arrest him if the panel decided in his favour.

Is the UK government likely to budge?

No. A government spokesman said the ruling "changes nothing", and maintained that Mr Assange had never been arbitrarily detained by the UK, and the Foreign Office would be formally contesting the UN panel's decision.

"An allegation of rape is still outstanding and a European arrest warrant in place, so the UK continues to have a legal obligation to extradite Mr Assange to Sweden," he said.

UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond branded the UN's ruling "ridiculous" and Mr Assange a "fugitive from justice", adding that he can come out "any time he chooses" but will still have to face justice in Sweden.

What's going to happen next?

Following the ruling, Mr Assange read a statement via a video link from the Ecuadorean embassy. He said the opinion of the panel was "vindication", adding: "The lawfulness of my detention is now a matter of settled law."

"It is the end of the road for legal arguments by the UK and Sweden. Those arguments lost and the time for an appeal is over," he said. "It is now the task of the states of the UK and Sweden to implement the verdict. They cannot pretend to look tough."

The Metropolitan Police has said it will still arrest Mr Assange if he leaves the embassy. With no indication from the UK and Swedish governments that they will change their position, the embassy is where, for now, he remains.

- Published4 February 2016

- Published4 February 2016

- Published25 June 2024

- Published26 June 2024