Joint enterprise ruling: A moment of genuine legal history

- Published

Moments of genuine legal history are rare - and rarely clear to the public when they happen.

The Supreme Court's ruling on the controversial "joint enterprise" law is one of them - and in the years to come it will have a profound effect on the lives of victims, defendants, the nature of police investigations and prosecutions up and down the land.

If you think I'm exaggerating, just watch the video of the judgement: there is an audible gasp at about 7.40 when Lord Neuberger says decades of law has been wrong, external.

For years there has been a legal battle over joint enterprise and how it is used to convict secondary parties to a crime.

That legal war came to a head in the Supreme Court in the case of Ameen Jogee, jailed for murdering former police officer Paul Fyfe in Leicester.

While Jogee's co-defendant wielded the knife, he himself was prosecuted under the long-established principle of joint enterprise: the pair went out to commit a crime and Jogee could have foreseen the potentially fatal consequences of his partner's actions. And that, in the law, meant he was as guilty as the other man.

At the trial, the judge directed the jury that Jogee had to be guilty of murder if he had this foresight.

Ameen Jogee (left) and Mohammed Hirsi were both jailed for murdering Paul Fyfe under a joint enterprise conviction

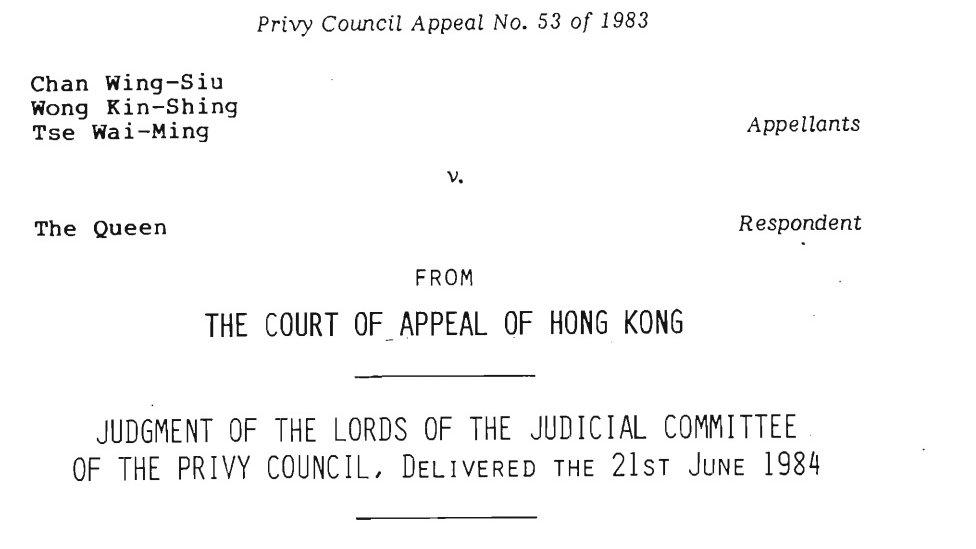

It's a legal doctrine largely dating back to a grim 1980 murder in Hong Kong that resulted in death sentences for the gang - who then battled for their lives all the way up to the Privy Council in London, then the territory's final court of appeal.

And that ruling, known as Chan Wing-Siu, external, has been part of the foundations for many similar prosecutions and convictions, most obviously in gang murders when one individual commits the deed and others are said to have egged him on.

The Supreme Court has now said, external that the legal test is wrong because, put simply, prosecutors must prove that they not only had foresight - but intended the deed to happen.

'Automatic authorisation'

Let's take the obvious example of gang criminality. A group goes out to rob teenagers of their iPhones. They have all agreed to that crime and to split the proceeds.

A victim resists and one of the assailants produces a knife and inflicts a fatal blow.

Are all of the gang guilty of that murder or just the member with blood on their hands?

The ruling will change the way complex gang-related crimes are prosecuted

For years, juries were told that to convict the other gang members, they simply had to be sure that they foresaw the possibility that the killing might occur.

If the other gang members did foresee such an eventuality, that wasn't just evidence of assistance but "automatic authorisation" of the crime.

This case law has proven to be very useful to prosecutors because it has helped them to haul entire gangs into the dock, even if individual members claim they had no intention to be involved in murder.

But critics of joint enterprise - and there are many - say this is "lazy law" because it leads to guilt and imprisonment without producing evidence of intent.

And the Supreme Court has largely agreed with that analysis.

What does the joint enterprise ruling mean in practice?

The correct test for juries, say the justices, is that they must be sure that the other gang members definitely assisted or encouraged the attacker to do the deed. A murder conviction cannot follow from just being physically present, they had to be mentally signed up too.

"The error was to treat foresight... as automatic authorisation [of the crime]... whereas the correct rule is that foresight is simply evidence of intent to assist or encourage," says the Supreme Court in its highly readable legal summary, external.

"It is a question for the jury in every case whether the intention to assist or encourage is shown."

Appeals to follow

So does this mean that everyone convicted, partly or otherwise, under this long-established principle is guilty of a miscarriage of justice?

There are sure to be many, many appeals - but the Supreme Court clearly takes the view that many convictions are safe.

The case that began it all: Hong Kong Murder led to Supreme Court ruling 30 years on

The ruling says anyone who joins a crime knowing someone could come to harm can still expect to be convicted of manslaughter if a death then occurs.

Secondly, the court says it has not undermined the basic principle that anyone assisting and encouraging wrongdoing is as guilty as the person who physically carries out the act.

Finally, the justices metaphorically underline in red ink, juries are still free to infer that someone was involved in a joint enterprise if the evidence clearly shows it, such as "weight of numbers in a combined attack".

So if the prison gates are not going to be swinging open, why is this such an important ruling? Quite simply, because it's about justice and how it has to be applied to all.

Felicity Gerry QC, the lead barrister for Ameen Jogee, says that the challenge to joint enterprise was about a fundamental question of fairness.

"It's not about gangs, it's not about people who intend to participate in serious crime," she said after the victory. "It's about those who are accused of assisting or encouraging or are on the periphery and that we make sure that we deal with trials in a fair and balanced way, not just scoop everybody up."

So what of Jogee himself? For now, he remains in prison ahead of more legal argument on whether he should face a murder retrial or see his conviction changed to manslaughter.

- Published18 February 2016

- Published18 February 2016