Budget 2016: Disability benefits savings offset by rising costs

- Published

There are people getting disability benefits who don't deserve them.

And there are others who don't need as much money as they're getting.

That in essence has been the view of successive governments as they've tried to reduce the amount the state pays in disability benefits.

It assumes there is a large group of undeserving benefit recipients that can be flushed out with increasingly focused assessments. The evidence, however, suggests that's simply not true.

Following Wednesday's budget announcements, the immediate focus is on PIP, Personal Independence Payment, which is replacing Disability Living Allowance. The government plans to tighten the criteria for the benefit, saving £1.3bn by 2020, and affecting 640,000 people.

Claimants, including those currently on DLA, are assessed for their eligibility by the DWP. It's a two-step process. People complete a self-assessment form and supply medical evidence, before undergoing a test carried out by Atos or Capita on behalf of the government.

The aim of PIP is to ensure people get the right help - and to save money. But consistently, officials have had to increase the cost of the benefit.

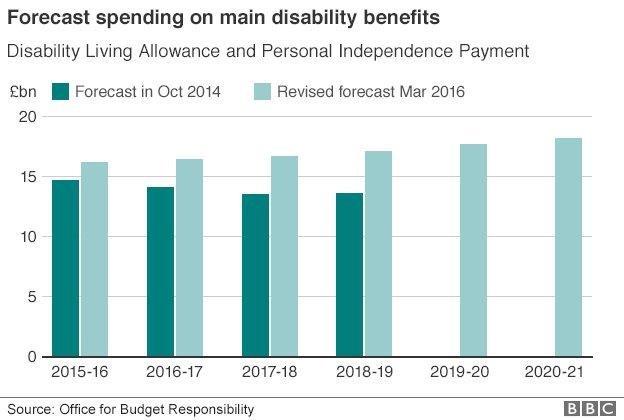

In October 2014, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast that spending on disability benefits between 2015 and 2019 would total £55.9bn. In its forecast on Wednesday, that figure had risen to £66.4bn - an increase of £10.5bn.

The OBR said the rising costs were because of higher-than-expected caseloads - and people getting more money than ministers had predicted. The average payout is now £100 a week, 14% higher than expected.

"The introduction of PIP is generating much smaller savings than the government was aiming for," it said.

Even if the government manages to push through its latest reforms, and some Tory MPs are said to be queasy at the prospect, costs will still increase according to the OBR - to £17.7bn in 2019-20 and £18.2bn in 2020-21.

What are Personal Independence Payments?

PIPs are benefit payments to help people aged 16-64 with "some of the extra costs caused by long-term ill-health or a disability", external.

They are available to employed and unemployed people and claimants can receive between £21.80 and £139.75 a week, depending on how their condition affects them.

This is determined by an assessment and claimants are regularly reassessed.

From April 2013, PIPs began replacing Disability Living Allowance.

This process is ongoing and the government says everyone who needs to switch to PIPs should have been contacted by late 2017.

Costs have also risen because claimants are being increasingly successful in appealing against officials' decisions, often helped by charities. The DWP hope to stop that - a little-noted item in the Budget gave the DWP £22m to hire more staff to attend to the appeals and put the department's case.

Budget 2016: 'Disability budget going up' - Osborne

The problems with PIP are mirrored by ESA, Employment and Support Allowance, the main sickness benefit.

When the Labour government announced the idea in 2006, they predicted that within a decade, a million fewer people would be claiming it than the payment it was replacing, incapacity benefit (IB).

A decade later, the number of ESA recipients is virtually the same as those who were getting IB in 2006. Internal DWP documents I saw in 2014 described ESA as "one of the largest fiscal risks currently facing the government". Costs since then have continued to rise.

With so many errant forecasts, it's little wonder the OBR said that the over-optimism about how much welfare changes will save is an ongoing problem.

But despite these challenges, the OBR also concluded that the government is on track by 2020-21 to spend the lowest amount on welfare, as a percentage of GDP, in 30 years.

- Published17 March 2016