The moped plot: From west London to Syria

- Published

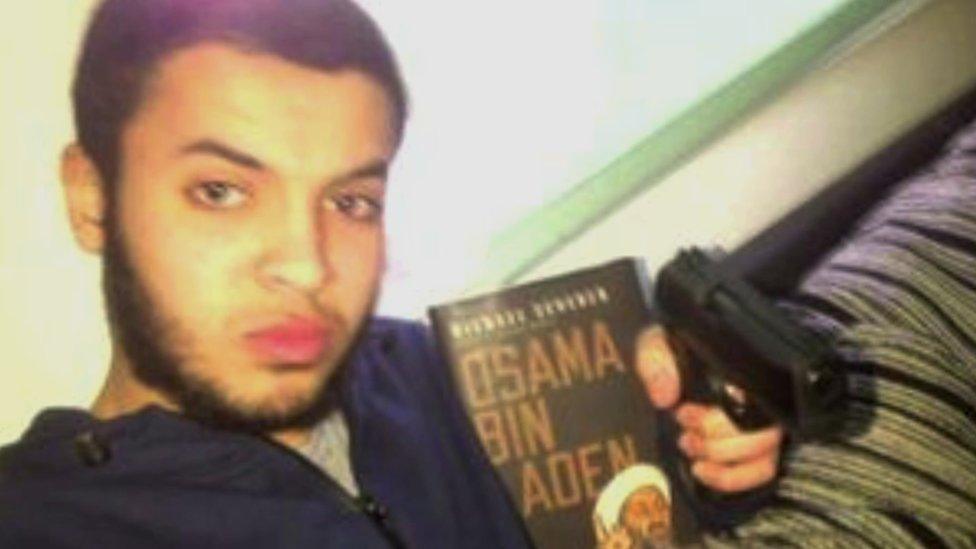

Tarik Hassane didn't hide his views

Two men are facing life sentences for being part of a plan to stage a drive-by shooting in west London in 2014. The plot was among the first major cases uncovered by police and MI5 linking plans to attack the UK with events in Syria.

Tarik Hassane, 22, had wanted to be a heart surgeon.

A happy, popular boy in west London, he grew up with a social conscience. He took part in an anti-knife crime video. He studied hard to learn the medicine that would help him save lives.

However, he later swore allegiance to the self-styled Islamic State and orchestrated a plan to carry out a drive-by murder close to his home.

Hassane hasn't given an account of his journey to extremism.

When he changed his plea to guilty halfway through the trial, he showed no emotion until after the judge and jury had left court.

Then, quietly, he began to weep. His co-defendant and school friend, Suhaib Majeed, hugged him. And then, wiping his eyes, Hassane left the dock for prison.

Majeed and Hassane were followed in London

In 2014 Hassane, the son of a Saudi Arabian ambassador, was studying medicine in Sudan.

He was sharing vile and violent material online. And he was planning to kill police or soldiers in London in order to spread fear and panic across Britain.

Hassane didn't hide his beliefs. When he was still at school, he had been reported for calling for attacks against Israel during Friday prayers.

And in early 2014, he told Majeed, 21, he had pledged allegiance to Islamic State and urged others to do the same.

'Turnup Terror Squad'

He was a prolific user of social media and one of his chat groups was called the Turnup Terror Squad.

On Twitter, he fancied himself as a young Islamic scholar, capable of telling others whether they were good or bad Muslims.

But away from the theorising, he was looking for a practical way to demonstrate his allegiance to IS - and his solution was simple: First, get a gun. Second, a moped. Third, somewhere to hide it.

Then identify a target, kill them, and, finally, escape convinced he had shaken Britain to its core.

Majeed threw this gun away as police came to arrest him

Court eight of the Old Bailey heard how the focus of all this planning was the sprawling warren of streets either side of the Westway, the enormous flyover that carries traffic from central London to the suburbs.

In the shadows of this concrete and tarmac behemoth, London's wealth and poverty sit cheek-by-jowl.

There are gentrified neighbourhoods where a five-bedroom home will set you back millions of pounds.

And there are far poorer streets where a gang sub-culture causes misery. And among some of these young men, a jihadist ideology has long been developing and strengthening.

Pistol and bullets

Suhaib Majeed, described in court as obsessed with the "warped ideology" of IS jihadist violence, grew up alongside Hassane in these streets.

And it was in one dark corner of the Brunel housing estate that Suhaib Majeed met up one evening with Nyall Hamlett, 25, to receive the gun at the heart of Hassane's plan.

Majeed, like Hassane, was academic. The British-Iraqi was reading physics at King's College London and apparently aiming to study for a master's degree.

Hamlett had got to know Majeed and Hassane at the major al-Manaar Mosque in Acklam Road, where he had been working as a chef in the cafe after his release from prison.

Unbeknown to the men, surveillance officers were watching and saw Hamlett hand over a bag containing a semi-automatic Russian Baikal pistol, silencer and bullets.

Nathan Cuffy supplied the firearm to Hamlett, who passed it in a bag to Majeed

Hamlett's criminal past

Jailed in 2010 for four years for trying to smuggle a quarter of a kilo of cocaine from Jamaica through Gatwick Airport

Returned to prison for possession of heroin

Says he converted to Islam while in prison

Adopted the name Omar

Hamlett had received the weapon from his old school friend Nathan Cuffy, 26. The pair had been altar boys while at St Mary of the Angels Primary School, just around the corner from where the gun transfer took place.

Cuffy, who suffers from sickle cell anaemia, had been a drug user since he was 13 and also had a string of related convictions.

Both he and Hamlett admitted their role in sourcing and handing over the gun - but both denied knowing what Hassane wanted it for. They denied being part of any terrorist plot - and an Old Bailey jury cleared them of involvement and conspiracy to murder.

West London youth worker Manni Abdul Karim Ibrahim says it is no surprise that firearms could be passed from criminal gangs onto aspiring terrorists.

"There is an issue with criminal gangs, violent criminal gangs, having access to firearms. So if you are a young person who has grown up in an estate where there are gangs who are involved in serious violence, then it doesn't take much to get a firearm off them even if you are not a member of the criminal gang itself. You can approach them and say, 'look, I need a firearm', and that's it."

West London fighters: (L-R) Choukri Ellekhlifi, Mohammed el-Araj and Mohammed Nasser

Westway to the Caliphate: The west-London IS connection

There is no official figure for the number of men or women from west London who have gone to fight alongside IS or supported it in other ways

The BBC's unique public database has identified more than two dozen individuals

At least 11 west Londoners have been killed - and three of them were friends of Hassane and Majeed

Two of those three men were at the same school as the hostage killer Mohammed Emwazi, known as Jihadi John

As the summer of 2014 progressed, the security service and counter-terrorism detectives were taking an increasingly urgent interest in a pool of suspected IS supporters across west London.

As autumn approached, Hassane and Majeed had become a priority and Scotland Yard placed their network under surveillance.

Officers followed them around, photographing them in the street, establishing their patterns and connections.

At one point, they saw Majeed sitting under a tree in Regent's Park, using his laptop for a highly encrypted online chat with a jihadist overseas.

Police have never discovered what was said but they suspect the contact may have been in Syria.

Majeed was watched and monitored

When those officers observed Majeed taking a gun from Hamlett, they moved in to arrest him and others - even though Hassane himself, the leader of the plan, was out of the country.

When police came for Majeed, he threw the gun out of the window.

On 4 September, Hassane had gone back to university in Khartoum and, despite knowing Majeed and others had been arrested, he returned weeks later.

The trial heard that on 1 October, Hassane had used his iPad to carry out Google Streetview searches of Shepherd's Bush police station and the nearby Territorial Army barracks.

This amounted to "hostile reconnaissance", said prosecutor Brian Altman QC, proof that Hassane was determined to press on with a "lone wolf" attack.

Hamlett and Cuffy denied being part of the terror plot, but pleaded guilty to firearms offences

On 6 October, Hassane went to an internet cafe - rather than using his iPad.

A surveillance team saw him using Skype and another chat app, speaking in a low voice and, eventually, becoming agitated.

He got up, muttering and tutting, the court heard. He threw down the headphones he had been wearing and stormed out.

Moments later, he returned and tried to log back in. He then left again, apparently relieved that the record of his activity had been wiped from the computer.

The following day he was arrested.

Directed or inspired?

Hassane and Majeed now face life imprisonment - the mandatory term for conspiracy to murder.

So was his plot organised and orchestrated by IS leaders in Raqqa or a sophisticated case of DIY terrorism? Whitehall security chiefs were so concerned by the intelligence from this investigation and other operations during the summer of 2014, they decided to raise the official threat level to "severe", external - meaning an attack was, in their view, "highly likely".

It was part of what they regarded as evidence of "blowback" - the threat of violence on the streets of Britain because of the involvement, directly or indirectly, of Britons in Syria's conflict.

When last year the prime minister told MPs that the police and security services had disrupted seven plots, external that were "either linked to ISIL or inspired by ISIL's propaganda", Hassane's plan was one of those in his mind.

Hassane was, at the very least, in the inspired category. But there are hints and suspicions that IS figures could have been more deeply involved - from Majeed's encrypted communications in the park through to Hassane's peculiar behaviour in an internet cafe.

Security chiefs aren't saying what more they know. One thing is for sure: Hassane thought he was doing what was expected of a loyal servant of the self-styled Islamic State.