Can an inquiry into secrets ever be public?

- Published

What's behind the mirrored windows?

Whatever you may read elsewhere, don't believe for a moment that police and spooks freely give away secrets. If they did, by definition, they wouldn't be secret.

That is the price an otherwise open society pays if it wants agencies involved in secret activity to protect the public.

And that's also the great big problem on the desk this morning of Lord Justice Pitchford, the chair of the forthcoming public inquiry into undercover policing.

Tuesday sees the start of two days of legal arguments over what M'Lud should disclose about the allegations that undercover police were involved in clandestine relationships, stealing the names of dead children and downright dodginess up to and including spying on Stephen Lawrence's family.

He says he wants it to be as open as possible. But can his inquiry ever tell the public the full truth? And if not, how much secrecy is too much secrecy?

The core participants to the inquiry, such as the women who unwittingly entered into relationships with undercover officers, say there must be transparency, external.

Undercover officers and their operations going back 40 years must be examined.

Names must be named. If the inquiry fails to do so, how can it discover the full extent of potential wrongdoing?

Secrecy, they predict, will be used to hide the truth, avoid embarrassment and escape public accountability.

Most of the UK's major news organisations, including the BBC, are also arguing for as much openness as possible.

Undercover inquiry: The key issues

How and why did officers have relationships with women? How many did so?

Why did they use the names of dead children as part of their cover?

How many miscarriages of justice have they been involved in?

Did they monitor a group of MPs and trade unionists?

Did they monitor campaigns, such as the fight by Stephen Lawrence's family?

The Metropolitan Police thinks differently.

The force wants the inquiry to hear most of the detail behind closed doors. Lord Justice Pitchford will see and hear the evidence - but the complainants and public would not.

"In the overwhelming majority of instances the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) will be submitting that considerations of fairness and the public interest come down in favour of not disclosing the fact of or details of an undercover police deployment including, but not limited to, the identity of undercover police officer," it says in its published arguments, external.

The force has already accepted the women in relationships suffered an abuse of police power which was "abusive, deceitful, manipulative and wrong".

So how can it now be asking for the "overwhelming majority" of what it has to say about undercover work to be heard in secret?

Police chiefs say that officers who go undercover don't expect their employer to later put their names in the public domain. They have a legal duty of care towards their officers. Exposing their true identities would also expose them to personal risk.

But Peter Francis, the former SDS officer turned whistleblower, says that if the Met wants anonymity for his former colleagues, then it needs to provide evidence of the risks they face.

He stresses in his submission, external that he was never promised "lifelong" confidentiality when he went undercover and does not seek it now.

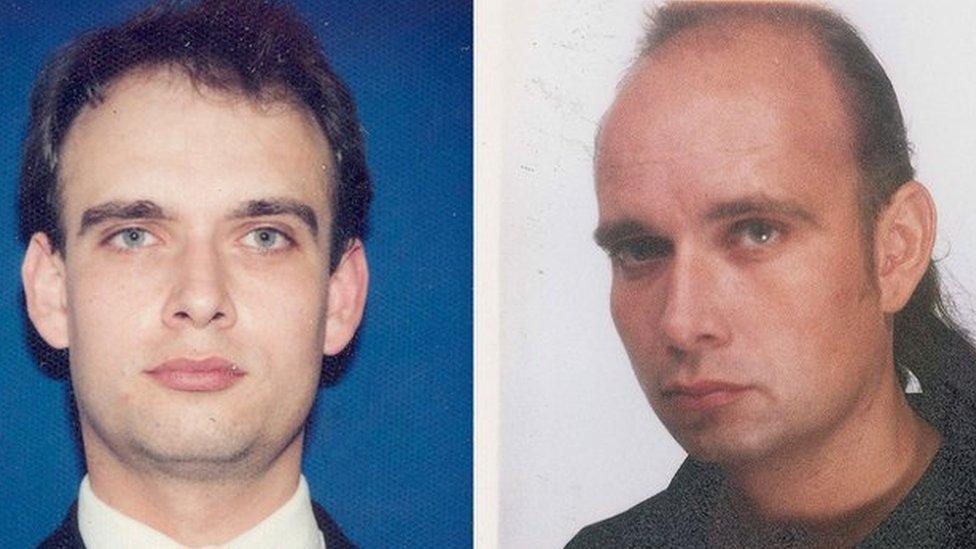

Peter Francis: Former undercover officer turned whistleblower

"He was unaware of the concept of NCND during the course of his employment," say his lawyers.

What's NCND? That's Neither Confirm Nor Deny. And this very spooky acronym is the real game afoot.

With apologies to scientists, NCND is to security operations what Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle is to physics. Both are about the inability to know for sure what exactly is going on.

When you look at a page of censored text, you have no idea what's underneath the thick black stripes. You may guess, but you have no idea at all.

Has MI5 infiltrated X or Y extremist cell? Not telling. Are undercover police hanging out with anarchists planning a violent demonstration Nope, still not telling.

Has some undercover operative broken the law... maybe by inciting otherwise law-abiding environmental protesters to cut their way into a power station. Not telling...

The Home Office, which ordered the inquiry, and the Cabinet Office argue the inquiry must protect NCND because its power lies not in denying the existence of operations - but consistently, absolutely consistently, refusing to give a hint one way or the other.

That uncertainty is its strength. If government and its agencies can avoid commenting, it makes it jolly difficult to establish anything at all about secret operations - thereby keeping those that do exist secure.

Critics of Neither Confirm Nor Deny say that it delivers neither truth nor justice - and there are precedents for eroding it.

Bob Lambert: Former officer who will be named in the inquiry

An important test case in the undercover affair, known as DIL, underlined existing law that there is a very strong public interest in protecting the anonymity of undercover officers.

It added there are exceptions, including naming an officer so as to prevent a miscarriage of justice or where it's irrational to claim their identity has not been already established.

The upshot was that the High Court confirmed the names of two SDS officers - Bob Lambert and Jim Sutton - but declined to name others.

And, quite separately, the inquests into the 7/7 bombings opened up NCND in a different way when MI5 revealed some of what it knew about the bombers before they struck.

Those disclosures were a very important acknowledgement by the state that transparency can trump NCND.

But there are also examples where attempts to force facts into the open have failed.

Five years ago, the government decided it would veto what could be published by a promised inquiry into allegations that British security agencies had got mixed up in rendition and torture following 9/11.

A host of participants - complainants, campaign groups and lawyers - walked out.

As legal rows grew and practical problems mounted, the inquiry looked as crippled as a racehorse that had fallen hard at the first fence. Eventually, the screens went up and the Detainee Inquiry was shot by the Whitehall vet.

As Lord Justice Pitchford's inquiry enters the starting gate for the 10.30 at the Royal Courts of Justice, that is the fate he will wish to avoid.

- Published28 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015