Thousands of police visits 'criminalise' children in care homes

- Published

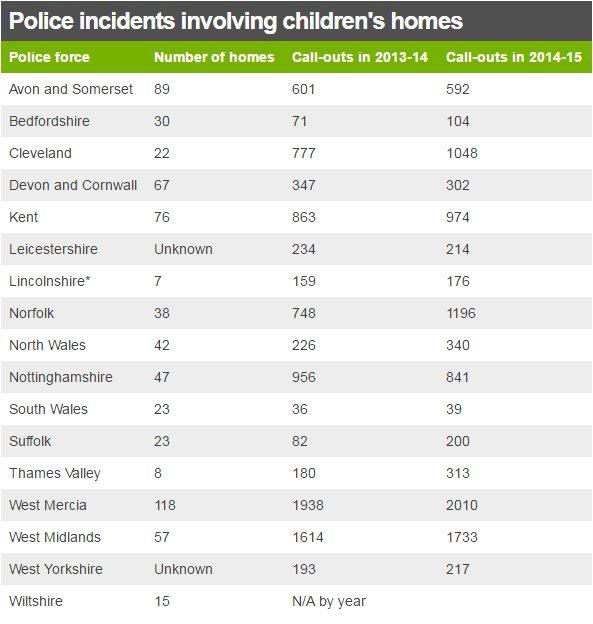

Police in England and Wales are being called to children's homes thousands of times a year, according to figures.

One force, West Mercia, saw the equivalent of more than five call-outs a day to homes in 2014-15, the Howard League for Penal Reform found., external

It said children were being wrongly "criminalised" because staff often called the police over minor incidents.

But the Independent Children's Homes Association, external said homes were "rigorously inspected" and staff well-trained.

The majority of children legally defined as "looked after" in England and Wales are placed in foster care, but in 2014, some 5,220 were living in residential care homes.

The Howard League's findings included:

Across 16 police forces in 2014-15, there were 10,299 call-outs or incidents - almost two for every child in a residential home

West Mercia, West Midlands, Norfolk and Cleveland all dealt with more than 1,000 cases that year - South Wales, with just 39, saw the fewest

In 12 of the 16 forces, the number of incidents rose, often significantly, between 2013-14 and 2014-15

The report also highlighted Department for Education figures which show a 13 to 15-year-old in a home is almost 20 times more likely to have contact with police than a child living with their family.

Taken together, the Howard League said it was clear children living in children's homes were "being criminalised at excessively high rates".

Staff are calling police too frequently, often over minor incidents that would never come to officers' attention if they happened in family homes, the charity said.

"There appears to be a 'tipping point' around the age of 13, at which time these children lose society's sympathy and, rather than being helped, they are pushed into the criminal justice system," the report added.

'Staff shortages'

Frances Crook, chief executive of the Howard League, said: "They are wonderful young people who have had a really bad start in life.

"Private companies, charities and local authorities that are paid a fortune by the taxpayer should give these children what they need and deserve."

The report also said:

government, police, councils and Ofsted are not doing enough to root out bad practice at the three-quarters of England's 1,760 children's homes that are run by private companies

police believe some homes use custody as respite to cover staff shortages and because staff are not trained to deal with children's behaviour

police lack confidence in the care given by some homes and believe vulnerable children would actually be better off in custody

Figures from different forces are not directly comparable because some include call-outs for missing or absent children, while others only relate to reports of criminal behaviour.

Children's homes are also not evenly distributed across the country, and West Mercia Police pointed out that its area contained more than any other force in England.

It said in a statement: "We work closely with partner agencies and each reported incident is carefully managed on a case-by-case basis. Police work with care homes and children exploring alternatives including restorative justice."

Restorative justice enables victims to meet or communicate with offenders to explain the real impact of the crime.

A West Midlands Police spokesman said: "Clearly there are times when an arrest is the most appropriate course of action when a serious offence has occurred and the suspect is a child; however for more minor incidents we utilise a variety of resolutions rather than an arrest."

'Build relationships'

Jonathan Stanley, from the Independent Children's Homes Association, said children's homes were "the most scrutinised and accountable service for young people".

"It seems that what is being reported here is history. Police and children's homes work closely together and meet regularly in local areas," he said.

"That's not to say there aren't some particular issues but this needs real life, detailed evidence in order for them to be understood."

Olivia Pinkney and Nick Ephgrave, from the National Police Chiefs' Council,, external said police "should not be called to minor incidents which would otherwise be dealt with in a family environment".

They said where intervention was necessary, officers should consider tools like restorative justice, and make every effort to avoid holding young people in cells overnight.

They added: "By engaging with 'looked after' children in non-crisis situations we can help build positive relationships and earn their trust.

"All of this will be impossible, however, without better data - which is currently lacking."

Children's Commissioner Anne Longfield said: "Ensuring that staff are able to work in partnership with the police to positively deal with difficult behaviour will be essential if we are to offer children with particularly challenging behaviour the guidance and support of a parent - in this instance a corporate parent."

- Published23 March 2016

- Published4 August 2015

- Published18 June 2012