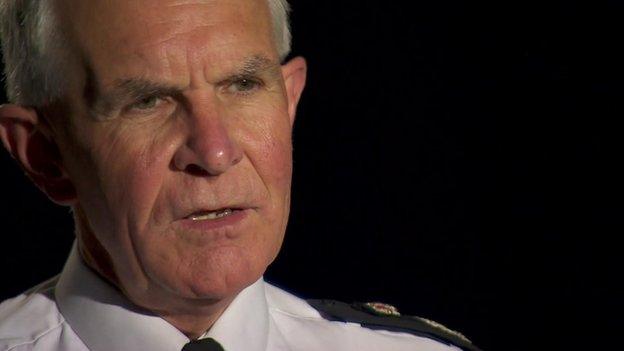

Sir Peter Fahy: Missing teen searches 'unsustainable'

- Published

Tracing missing teenagers is better dealt with by social workers, says Sir Peter Fahy

Time spent tracing missing teenagers is an "unsustainable" burden for police, one of the UK's most senior chief constables has warned.

Sir Peter Fahy, of Greater Manchester Police (GMP), said other police work was compromised by thousands of calls better dealt with by social workers.

He said it cost the force £30m a year.

English, Scottish and Welsh police dealt with 306,000 missing people in 2012/13, according to the latest UK Missing Persons Bureau figures.

And each missing person call costs an average of £1,325, said researchers at Portsmouth University.

Many cases involve young people who repeatedly run away from care homes. Some go missing, and are then found and returned by police officers, hundreds of times.

Most of the work done by Greater Manchester Police's Protecting Vulnerable People team involves tracing missing teenagers

It is vital work, not least because of the strong correlation between youngsters who go missing, and those who fall victim to child sexual exploitation.

Sir Peter stressed the priority must be to protect children, but he questioned whether police officers were the best professionals to be dealing with what was a complex problem.

'Different approach'

"The public and politicians have made it clear that they don't want to see young people being put at risk in these situations because of the concern about what happened in places like Rochdale and Rotherham," he said.

Sarah says she would be dead if she had not received help from the Children's Society

Sir Peter added: "We need a different approach."

GMP's response to the problem has been to set up a special team of detectives, dedicated to tracking down and returning missing people.

Protecting Vulnerable People

BBC News was given exclusive access to the Protecting Vulnerable People team.

During three days with them, we found that most of their time, both at HQ and on the ground, was spent trying to find "Repeat Missing" young people.

One girl, a 15-year-old, was missing for the 49th time this year. Several detectives spent many hours searching for her in city centre hotels, on the streets and at addresses across the city.

Eventually she returned to the care home where she lives of her own accord, oblivious to the fact that her case had cost the police here an estimated £70,000 since January.

The problem is not limited to Manchester; it is a challenge for police forces across the UK.

Sir Peter's comments on what he called an "unsustainable" situation feed into the debate started by the head of the new Police Chiefs Council, Sara Thornton, who said that the public should no longer expect to see a police officer following crimes such as burglary, and encouraging a "conversation with the public" over priorities.

'Cancelled appointments'

Referring to the workload placed on police as they tracked down missing people, Sir Peter said: "Every single day, sergeants and inspectors have to make hard decisions about what they are going to do, and missing children will always be top of the priority list.

"That means there will be other calls that we can't attend to, where we try to deal with them on the phone and where, perhaps appointments get cancelled, where crimes are put off to be investigated on another day."

But central to his point is the suggestion that young, vulnerable people may be better dealt with by social workers, rather than police officers.

"When you have somebody who constantly goes missing, it is not really for me a police issue. It is really, absolutely, a social work issue," he said.

Police chiefs argue other work is comprised by missing person investigations

He added: "There are other professionals who are really better trained to deal with this. And that is really part of the discussion we have to have with other agencies."

'Last line of defence'

Some of those other agencies agree that early intervention by other professionals may be more beneficial for the young people concerned, and more cost-effective too.

Paul Maher, of the Children's Society, said: "Crisis intervention by the police is more costly. The early prevention that we do raises awareness. We can engage with young people so they can, at an early age, understand the risk that they are putting themselves in when they go running away."

However, Andrew Christie from the Association of Directors of Children's Services says it's important agencies work together.

"Young people who go missing have usually entered care as teenagers and have very complex needs and behaviours which we are trying to change. It requires the help of all agencies, including the police, to change these behaviours, and to recover the young people who have gone missing, sometimes several times.

"While we do recognise the additional burdens facing the police service, they do share a legal safeguarding duty and in return it needs to be recognised that our members are facing similar pressures."

The Minister for Preventing Abuse and Exploitation, Karen Bradley, said they expect all agencies, including the police, to work together to identify and protect missing young people.

"We are working with other departments to reduce unnecessary demands on policing to ensure officers do not have to pick up the pieces when other public services fail to deliver."

For now, many police forces find themselves, at times, the last and only line of defence in protecting vulnerable young runaways.

And for those at the sharp end, like PC Helen Boyle of GMP's Protecting Vulnerable People unit, there is no doubting the importance of the work they do.

"If we take our eye off the ball, the bottom line is that these children could be killed. It is as simple as that. They could die because they end up putting themselves in positions that they can't get out of," she said.

- Published9 July 2015

- Published5 March 2013