Could British invention foil terror bombs?

- Published

The BBC's Frank Gardner has been to find out more about the bomb detection device

Europe has now suffered two major terrorist attacks in under six months. A total of 162 people were killed in the Paris and Brussels attacks in November and March respectively, not including the attackers.

Inspired and directed by so-called Islamic State (IS), they detonated a total of eight bombs, using powerful explosives, reported, but unconfirmed as TATP (triacetone triperoxide).

Since then, European governments have been looking hard at what, if anything, can be done to prevent a repeat of these attacks.

Specifically, is there a device on the market that could be installed, without exorbitant cost, to detect the presence of explosives in a crowded space such as an airport or station?

Scientists at Britain's Loughborough University, in the East Midlands, believe they have invented the answer: an explosive residue detector, external that uses cutting-edge laser technology.

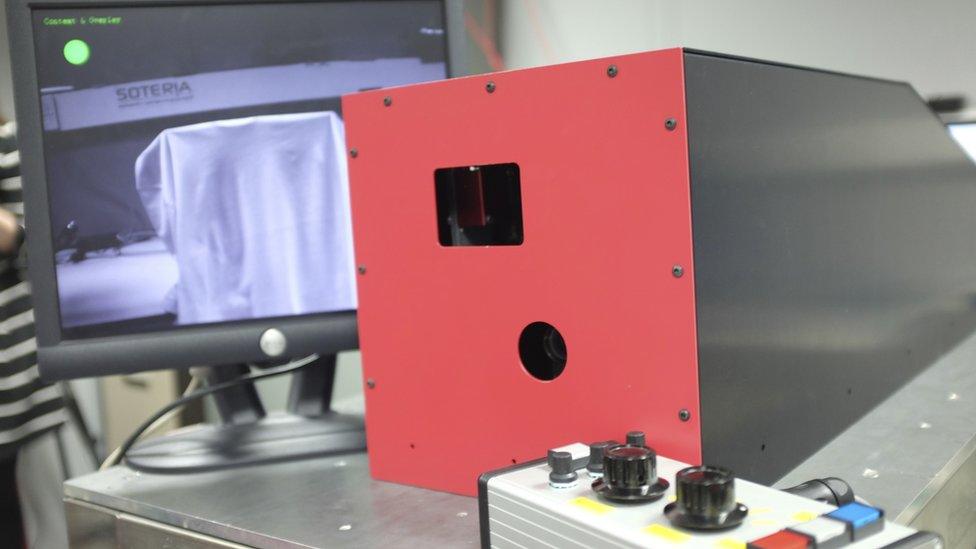

The equipment in question, dubbed the ExDetect, is neither discreet, quiet, nor blessed with any great aesthetic appeal - but, according to Prof John Tyrer, it is non-intrusive and could be just what is needed to save lives.

"I'm sorry to say, but the Brussels attack, this would have instantly sorted out the terrorists before they came into the terminal, and similarly the concert in Paris," he says.

"If it had been on the doors there, it would have stopped people getting in."

Inside a high-security laboratory in a corner of East Midlands Airport, Prof Tyrer's team shows me how it works.

First, a microscopic amount of Semtex 1A high explosive is dabbed onto a T-shirt.

To the naked eye, it is almost invisible - but from a large, red, metal box mounted on a portable steel trolley an ultra-violet laser beam flickers on to the white cotton surface of the garment.

The detector could potentially save many lives

Immediately, a warning flashes up on the display monitor.

The word "detected" appears in bold red letters, and a yellow circle highlights an illuminated red patch where the Semtex has touched the T-shirt.

In practice, says Prof Tyrer, if the device was deployed at, for example, an underground railway station, a silent alarm would alert an operator, prompting the ticket barriers to automatically close and bringing officials to carry out manual checks using a swab stick.

Sticky explosives

Judging by the pattern of recent events, most suicide bombers would probably then detonate their device, but Prof Tyrer points out that at least the bomber would have been prevented from boarding a crowded train.

"Explosives are sticky," says Prof Tyrer, "they leave fingerprints everywhere, even days later, and the ExDetect can find particles that weigh just millionths of a gram."

Prof Tyrer and his team, from the university's department of mechanical engineering, have spent 15 years developing this technology, at a cost of nearly £4m.

Would the Loughborough tech have stopped the Brussels airport bombing?

Each laser box, or "head" as it is called, costs about £250,000.

To effectively scan cargo from 360 degrees, he says, it needs two such devices aimed at an oblique angle.

The cost, he has suggested, could be offset by incorporating it into ticket prices.

Tellingly, the team's laboratory is less than a mile from the UPS parcel depot in East Midlands Airport where in 2010 a laser printer ink cartridge bomb was discovered in cargo sent by al-Qaeda in Yemen, bound for Chicago.

Initial searches by the Metropolitan Police's counter-terrorism detectives failed to find the bomb, which was removed only after the exact package number was passed on by a Saudi informant inside al-Qaeda.

Cargo is the Achilles heel of transport security, says Prof Tyrer, pointing out that cargo in the UK is subjected to six times more scanning than in France.

A bomb inside a soft drink can is thought to have brought down a Russian Metrojet plane last year

Fears over cargo safety have been raised recently, after so-called Islamic State claimed to have placed a bomb inside a soft drink can on a Russian Metrojet passenger plane, external in October 2015, bringing it down over the Sinai desert and killing all 224 people onboard.

So, I ask Prof Tyrer, if his team's invention is the answer to stopping bombs - or at least making it harder to smuggle them into crowded public places - then why has the government not bought this device in bulk and installed it?

"The problem we have with a lot of new technology like this, particularly in the security business, is that it's a distressed purchase, we have to wait until people need to buy it badly enough," he says.

The Department for Transport said: "We keep security under constant review, but for obvious reasons we do not comment in detail on specific measures."

- Published22 March 2016

- Published9 April 2016

- Published23 March 2016

- Published23 March 2016

- Published6 November 2015

- Published8 November 2015