Huw Edwards: On a high-stakes chat with Barack Obama

- Published

President Obama: "I implore you to reject those calls to pull back"

It all started with an unexpected phone call last week.

Two officials were on the line from the US Embassy in London and from the White House.

They wanted to talk about the president's forthcoming visit, and they were dealing with countless options for media interviews.

They had decided there would be one broadcast interview during the visit, and they were "wondering" whether I'd be interested in taking it on.

They did not have to wonder for very long. A fraction of a second is all it took for me to summon my calmest voice and say "certainly, of course, you bet, absolutely" and any other number of ways of saying yes.

Interviewing the most powerful man in the world is not an opportunity granted to many journalists.

It was already clear before he arrived in the UK that the president would have some controversial things to say about Britain's future in the EU.

What no-one had expected was the force of that intervention and the bluntness of the language: "back of the queue" is not only un-American in style (as many have pointed out) but also notably stark in tone.

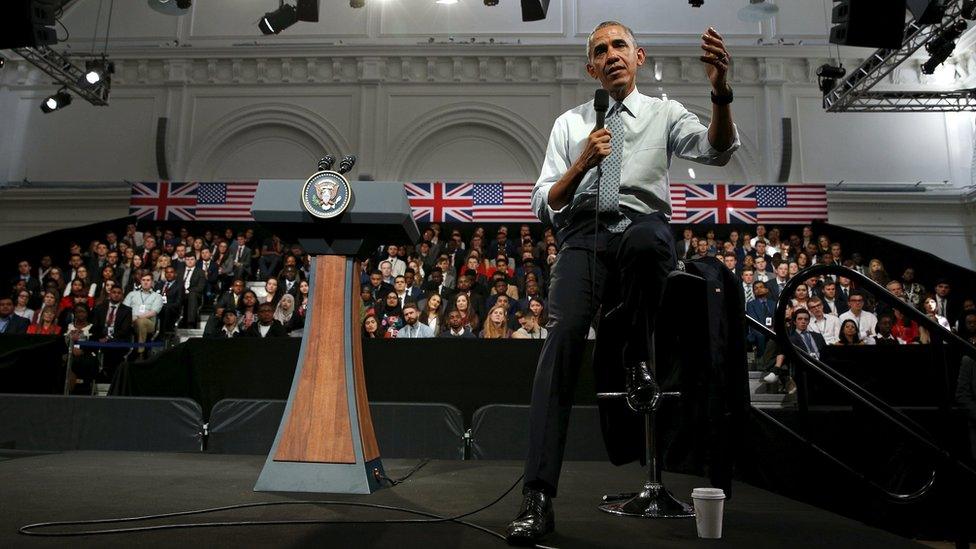

The president spent the morning at a so-called town hall event involving hundreds of young people at a venue in Westminster.

He is clearly at home with this format: he was relaxed, humorous (in a cool, self-deprecating way), informed, engaging, and happy to admit that he didn't have answers to some of the questions.

President Obama answered questions during a town-hall event in London

I watched some of the exchanges and then left to prepare for the interview in an adjoining room.

The crew had set up cameras, lights and sound the previous day and were ready to go. All we needed was the president.

Anyone who reckons that interviewing a serving US president is a breeze needs to pause and think.

The potential global audience is huge, the matters to be discussed are extremely important, and there is no room for error. There is no hiding place.

'Searching questions'

The stakes for the president are always sky-high, in everything he does, but it is also true that the stakes for a journalist in this position are not insignificant.

We were given a one-minute warning for the president's arrival. Suddenly the door opened and there he was, smiling broadly, shaking hands firmly, greeting everyone warmly.

I had been given plenty of advice about reading the presidential body language during the interview.

The challenge for the interviewer is clear: to ask as many searching questions as possible within the allocated time. That time can be fixed or less fixed. It often depends on how the interview is progressing.

After his interview with Huw Edwards, Barack Obama and David Cameron played golf together

The president fielded the questions with his brand of polite firmness, even when repeatedly challenged about the meaning of "back of the queue", the offence and anxiety this had caused in some quarters, and the potential impact on the wider special relationship (intelligence-sharing, for example) of a British departure from the EU.

At another point he rejected suggestions that Europe's migration crisis has been caused in part by America's reluctance to take assertive action in Syria.

He did allow himself a smile when talking about his wife's importance to his presidency ("I am labour, she's management"), and about the experience of being driven around Windsor by the 94 year-old Duke of Edinburgh (a "smooth ride").

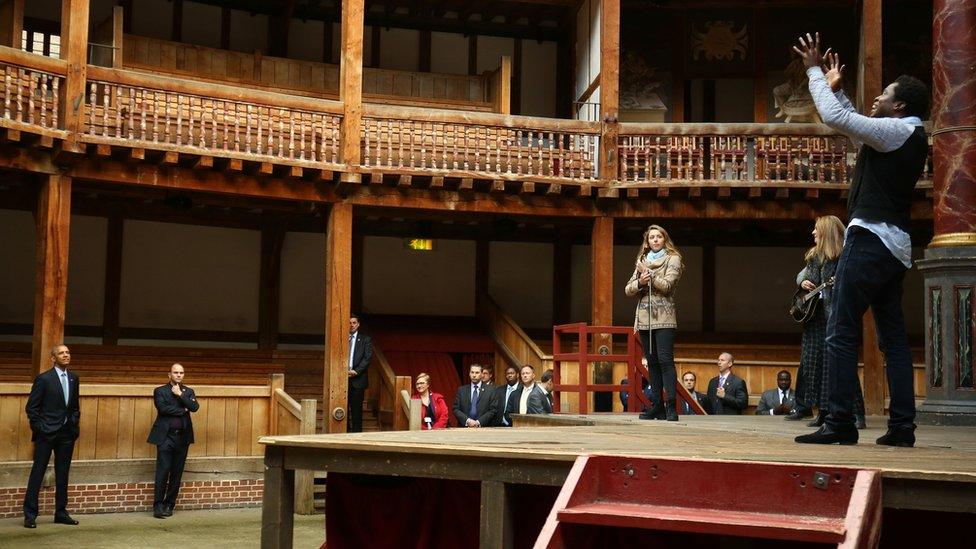

Obama watched scenes from Hamlet during a visit to The Globe

But this was above all a serious exchange about some of the biggest challenges of the day.

He thanked every member of the broadcast team before leaving the room, and chatted with a few of us about his love of Shakespeare (his favourites are Hamlet and Lear). He then left for a meeting with Labour's Jeremy Corbyn.

And a final thought: a president in his final year who can still enthuse a big crowd of young people - of all backgrounds - is an exceptional politician.

Whatever your views on his politics, that judgement is very difficult to deny.

- Published24 April 2016

- Published23 April 2016

- Published23 April 2016

- Published22 April 2016