Drone killings: Legal case 'needs clarifying'

- Published

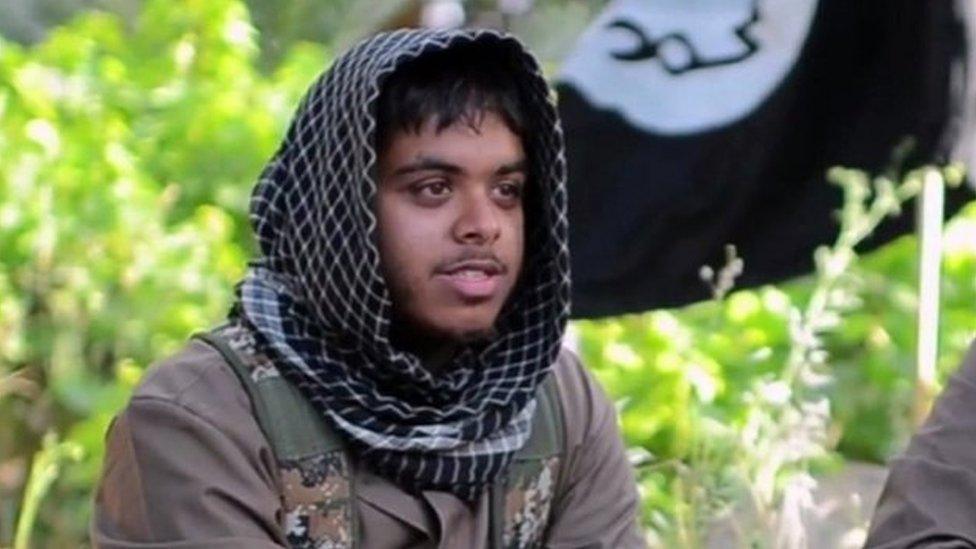

Cardiff-born Reyaad Khan was killed in a precision airstrike by an RAF remotely operated aircraft near Raqqa in Syria

The legal case for using drone strikes outside of armed conflict needs "urgent clarification" from ministers, a cross-party parliamentary committee has said.

The government insisted it did not have a "targeted killing" policy, but was clearly willing to use lethal force overseas for counter-terrorism, the Joint Committee on Human Rights said, external.

Two UK citizens were killed in Syria last year by an RAF drone.

The government says it takes "lawful action" over direct threats to the UK.

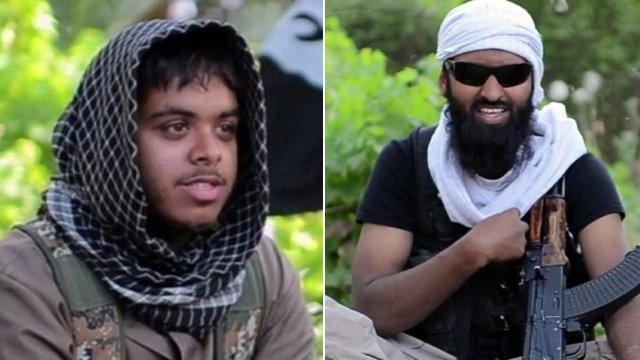

Reyaad Khan, a British member of the so-called Islamic State (IS) group, was targeted and killed by an RAF drone in Syria last August. Ruhul Amin, 26, from Aberdeen, also died in the strike.

'Self-defence'

Informing Parliament of the death, Prime Minister David Cameron said Mr Khan, 21, from Cardiff, had been plotting "barbaric" attacks on UK soil.

The British military was not authorised by Parliament to engage in military action inside Syria at that stage - but the strike was justified as an "act of self-defence", Mr Cameron said.

But that position is not justified under international law, and later statements justified the killing in the context of the armed conflict in Iraq.

The committee said it accepted that the drone strike had been part of the armed conflict against IS in Iraq and Syria, and therefore covered by the Law of War.

The RAF has been using remotely-controlled Reaper drones to bomb IS targets in Syria and Iraq

But there were contradictions and inconsistencies in the government's explanation of its policy on drone strikes, the committee added.

It said the government's policy on using lethal force abroad outside of armed conflict, and the legal basis for that, must be clarified.

The MPs and peers said international law permitting self-defence did not extend to using force "pre-emptively against a threat which is more remote, such as plans which have been merely discussed but which lack the necessary intent or capability to make them imminent".

'Take international lead'

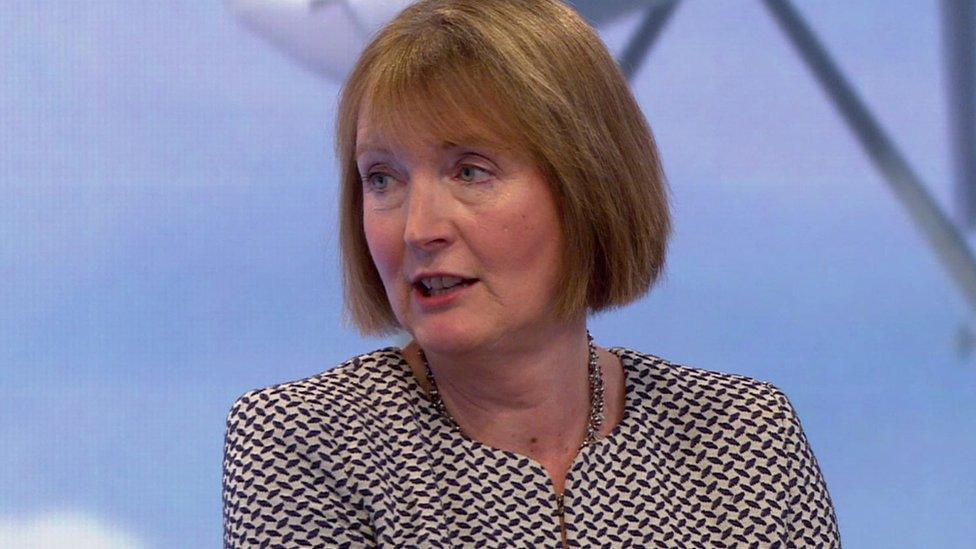

Committee chairman and Labour MP Harriet Harman said the legal justification for the drone strike on Khan was "confused and confusing".

She called for the UK government to lead the way internationally by defining a clear legal basis for action, and to make sure that those who made decisions were held accountable.

Harriet Harman says the law needs to be clear

"As the world faces the grey area between terrorism and war, there needs to be a new international consensus on when it is acceptable for a state to take a life outside of armed conflict," she said.

"Our government has said they're going to be targeting people in other parts of the world, but there's no independent scrutiny afterwards," she told BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

New technology and the rise of a force like IS had changed the traditional models of war, she added.

Clarification on drones was needed because the UK should abide by the rule of law, said Ms Harman, adding that those who killed people in strikes could later be open to a murder charge.

That risk and the opaque legal basis for drone strikes was an increasing cause of concern for military staff, especially as there were a number of investigations under way into soldiers' actions, external, said Col Richard Kemp, a former commander of British forces in Afghanistan.

"Many British troops feel they don't necessarily have the protection," he told the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

Clarity on the law and scrutiny of drone strikes were "important", he said, but added that the information used to scrutinise operations might be incomplete due to intelligence restrictions.

UK drone pilot, who operated in Afghanistan

I was hitting different targets - vehicles, compounds or individuals, such as the Taliban.

You can pull in any number of intelligence feeds to build up a target picture. There are experts who assess that piece of intelligence for their reliability - image analysts or linguists - and then you build the target in your mind.

When it comes to striking, you abide by the rules of engagement. [They] change depending on where you are and the type of threat you face.

Everything is dictated by the enemy on the ground and what that enemy does. If it presents a threat, then the situation will change.

The whole process is checked at every stage and it goes through lawyers. It's a robust process and always leans against carrying out a strike for the fear of collateral damage.

You're not thinking about taking a life, you're thinking about getting the sums right, getting your commands right, focusing on the target, what you think the weapon will do to the target.

During your first couple of times you do think about killing someone. But after that you just want to get it right, so you don't think about that.

No [I don't feel uncomfortable about what I did]. Ultimately it's my conscience, and my name on the bomb. I would never engage a target unless I was 100%.

Everything possible [is done to avoid civilian casualties]. We try and avoid any compound damage whatsoever.

No, never, never [do I think about what I did and the lives I took].

Listen to his account in full on BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

Strikes also fuelled resentment in the targeted country, said Jennifer Gibson, a human rights lawyer from Reprieve who represents families of drone strike victims.

She said: "If the UK is going to go down this road of engaging in targeted strikes, much like the US, there has to from the outset be a clear policy that sets out the legal framework within which these strikes are going to be taken and proper accountability mechanisms."

US actions

The committee also wants the government to set out its legal basis for assisting other nations, such as the US, in strikes against IS.

The US says it is in a global armed conflict with IS, so the Law of War applies and lethal force can be used anywhere in the world.

On Monday, a US strike in Iraq killed Abu Wahib, a senior Islamic State leader in Anbar province, and three other IS jihadists.

A UK government spokesman said: "Where we identify a direct and imminent threat to the UK we will take lawful action to address it and report to Parliament after we have done so.

"Such actions are only to be carried out as a last resort when all other options have been exhausted, and we would always do so in accordance with international humanitarian law."

- Published29 October 2015

- Published30 September 2015

- Published24 September 2015

- Published8 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015