Drone strikes: Do they actually work?

- Published

The United States is thought to have launched a secret drone campaign to kill Islamic State fighters in Syria.

Since taking office in 2008, President Barack Obama has made extensive use of drone warfare.

US drones over Yemen and Pakistan have targeted al-Qaeda relentlessly.

But while drones are capable of killing American enemies from a distance and without putting US military personnel in harm's way, critics question how far they bolster America's wider counter-terrorism strategy.

Defending the homeland

Brian Glyn Williams is a linguist who worked briefly for the CIA and the author of Predators: the CIA's drone war on Al-Qaeda.

"We had these attacks by al-Qaeda on our US embassies [in August 1998].

"So we knew al-Qaeda was a threat [and it] was based in these remote zones in southern Afghanistan under the control of the Taliban.

"We tried killing [Osama Bin Laden] on a couple of occasions with cruise missiles, fired out in the Indian Ocean, but they took too long to get to their target.

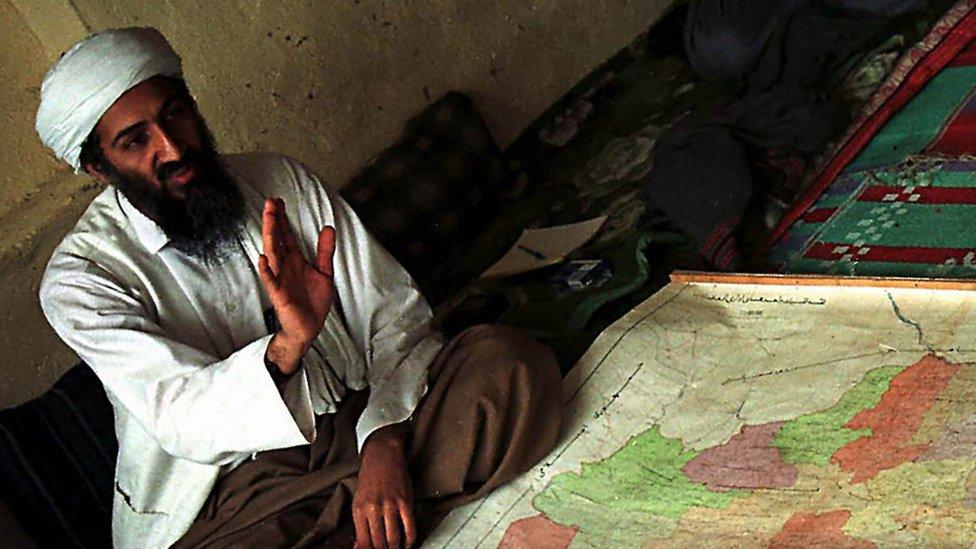

An unarmed US drone is said to have spotted Osama Bin Laden while he was in Afghanistan

"A drone flew over Bin Laden [not long before the 9/11 attacks] at a base in Kandahar in southern Afghanistan and actually saw him on the camera, but the drone was not yet armed at the time.

"So the dream was to have a "shooter", as they call it, that could hover over its target and kill them on the spot, directly when he was spotted.

"Drones are not robotic. They're flown by a pilot and before a drone strike takes place, you have to have spies on the ground that guide the drones to the Taliban and to al-Qaeda.

"Often times, they'll radio the co-ordinates of a Taliban meeting or a Taliban weapons depot or they'll plant a small homing beacon on a Taliban vehicle and these beacons then guide very small missiles directly to the targets.

"[Strikes that have killed al-Qaeda operatives who were planning attacks in the West translate to] no new mass casualty terror attacks since 9/11 in the US homeland. So I think that is a sign of success.

"What's the alternative? We saw the Pakistani army finally responded to these Taliban and al-Qaeda attacks on their country, and invaded the tribal zones just last year.

"During this operation, thousands of civilians were killed, with mass displacement, villages on fire, you know, it was like using a sledgehammer to get an ant."

Disrupt, degrade, dismantle, and defeat al-Qaeda

Shahank Joshi is a senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in London.

"The tendency to try and attack your enemies more and more remotely at bigger and bigger standoff ranges is a fundamental part of technological change. And drones are only the most recent part of that.

"Over 10 years of drone strikes haven't eliminated al-Qaeda as an organisation - but they have forced its operatives to be on the run, to communicate using extremely inefficient means that make it very difficult to conduct smooth plotting.

A Royal Air Force Reaper drone

"Al-Qaeda operatives understand that using cellular phones, email, satellite phones can allow intelligence agencies to give away their location, and so they have to rely on more old-fashioned ways of communicating.

"Osama Bin Laden's... couriers had to take messages physically out of the compound and deliver them from a long way away. It slows down communication.

"In some cases, like with al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, you have specific skills, like the ability to make undetectable bombs, that's held by particular individuals, so by killing the individual you've taken out a very key talent.

"But in most cases they've been able to replenish their leadership so it hasn't destroyed the organisation, all it's done is forced them to adapt, forced them to push new individuals through.

"In some cases, you have seen more radical, mid-level commanders replace what were more pragmatic, cautious commanders who were killed in strikes or raids at times, so it hasn't always had a positive effect.

"[In Yemen,] there have been some cases where very poor intelligence has led to the killing of senior tribesmen, and what that has done is suck new groups into al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, into al-Qaeda's Yemeni branch. So far from diminishing the threat, in places it has also worsened it.

"The mistake has been to think that you can engage in drone strikes without adequate intelligence. Where the intelligence is there, they have been reasonably effective. Where the intelligence hasn't been there, I think they have had more counter-productive effects."

Eliminate Safe havens

Prof Daniel Byman has advised the US government on counter-terrorism policy and served on the 9/11 Inquiry.

"You can have a safe haven like the Taliban's Afghanistan before the 9/11 attacks, where you have a supportive government that allows a terrorist group to organise [and] essentially build a mini-army with thousands of people being trained.

"There's an important difference when there's a safe haven in a warzone versus a safe haven in a country at relative peace.

"So in Pakistan, where the al-Qaeda figures in the tribal areas normally would be relatively safe, the drone campaign has put tremendous pressure on them.

"We have internal al-Qaeda documents that were captured where they're complaining that the training is miserable because people are afraid of being killed.

Image of a drone strike target

"In contrast, drone strikes on Islamic State leaders who are on the front lines in Syria or Iraq will have much less impact, these are people who are dodging death on a daily basis. So drones might make it slightly more dangerous, but they're not going to fundamentally transform the situation from a safe one to an unsafe one.

"The drone strikes first of all need to be a campaign, not just a one-off. You need to be convincing local militants that the strikes could happen all the time, anytime and thus affect their behaviour.

"Also, you need excellent intelligence, you need to convince the locals and the militants that the drones are hitting the right people and as a result the militants are afraid and the locals are less afraid.

"Drones are an important part of overall policy, but there should be a lot more and especially when you're going to have to deal with groups engaged in civil wars, you need to be doing a lot more.

"We should continue to do them in some places, but we should also be using other policy tools."

Counter al-Qaeda ideology

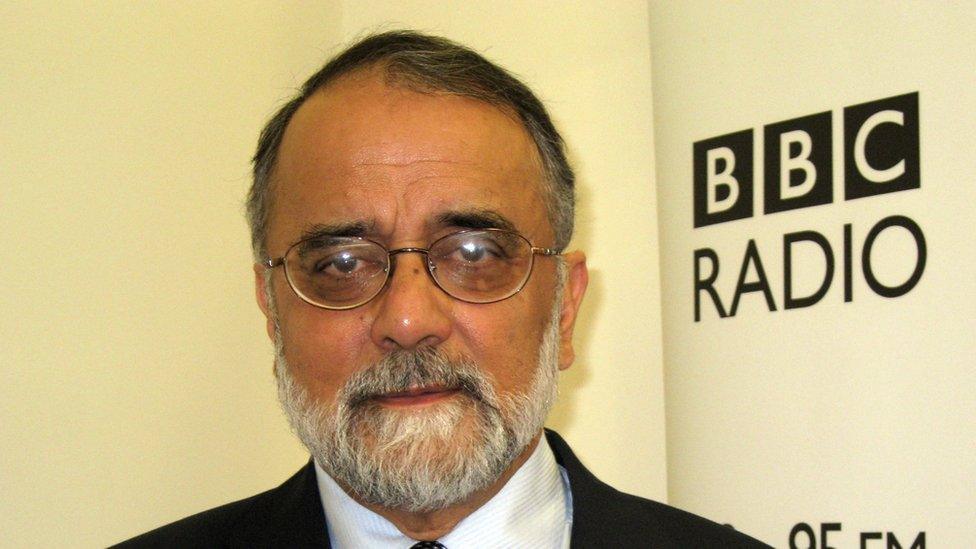

Ahmed Rashid is a Pakistani journalist and author and an expert on militant Islam.

"There's no doubt that drones, even if they just kill one civilian, are very easy to use as a propaganda tool to recruit young people, impressionable people.

"There was never any political strategy to win over the local population [in the so-called tribal areas in north-western Pakistan, from where al-Qaeda operated for years].

Ahmed Rashid believes that hearts and minds have yet to be won over about drone strikes

"This is a very rugged, mountainous region. There's very little arable land. There are very few prospects. Families are divided, and the issue of poverty is not resolved, because electricity, energy, gas, are all in short supply.

"A much more comprehensive strategy is needed [to win over hearts and minds] both by the Americans and the Pakistanis and the Afghans. And all that is completely missing.

"There is a very strong lobby of tribesmen who were in favour of drone strikes, because they hated the Taliban, and they hated al-Qaeda. Hearts and minds have not been won over.

"This war is still going on, many of these militants have moved into Afghanistan and now they've moved back into the tribal areas, this threat is not going to go away in a hurry."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 13:05. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published24 September 2015

- Published14 September 2015

- Published8 September 2015