Somme centenary: ‘Most powerful place on the Western Front’

- Published

A hundred years ago, thousands of soldiers left their trenches in what would become the bloodiest day in British army history.

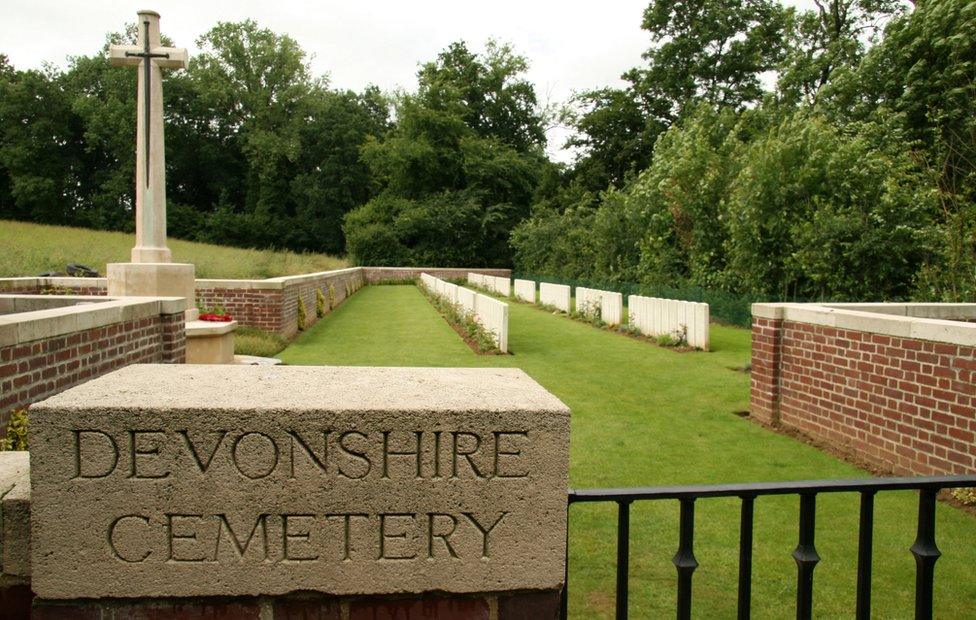

Among them were the Devonshire Regiment, many of whom were later buried in the trench where they began the day and still lie in the fields where they perished.

What was once a battle-scarred wasteland is now a neatly maintained, peaceful cemetery.

Surrounded by a cluster of trees called Mansel Copse, the site is separated from the village of Mametz by a shallow valley of French farmland.

Crossing that valley cost the lives of most of the men buried in the Devonshire Cemetery, as well as hundreds more.

'Danger spot'

One of the 163 men buried here is Capt Duncan Martin, external, an artist who made a plasticine model showing the threat facing his men.

Capt Martin was to lead a company of the 9th Battalion of the Devons to attack the German-held village.

He was "convinced" there was a German machine gun in the corner of Mametz's churchyard, and his model of the area pointed out the "danger spot", says historian and former soldier Tim Saunders.

Commanders saw the model, but Capt Martin's company was still sent into the fire of the machine gun.

"He was killed leading his men through the danger spot, as he predicted," Mr Saunders says.

Thousands of men left their trenches to attack the German lines on 1 July 1916

All but two of the men buried in the Devonshire Cemetery belonged to the 8th or 9th Devons, and all but three died on 1 July 1916 - the first day of the Battle of the Somme, during World War One.

But beyond these basic details, little is known about many of the soldiers in the Devonshire cemetery.

Most were in their 20s or 30s, though there were more than a dozen teenagers and three men in their early 40s.

In cases where a home town or next of kin's address is known, it is striking that many did not seem to come from Devon. They were from London, Birmingham, Lancashire and elsewhere in England and Wales.

A 'handsome chap'

Mr Saunders says the 8th and 9th Devons - both created after war was declared - were "fairly typical mid-war battalions" which by 1916 had "skin-deep" links to their county due to a continuing cycle of losses and replacements.

He says the 8th Battalion had been "very Devon" at the start of the war, while the 9th had always contained many soldiers from elsewhere.

One such solider was 2nd Lt Travers Adamson, a Dorset man who was 20 when he died.

Chris Copson, curator of the Keep Military Museum, external, calls Adamson the "epitome" of a World War One junior officer - a "handsome chap" smiling out of his photograph, part of a "generation brought up to lead".

He says such officers cared about their men, who cared in return.

In the Devonshire Cemetery - which he calls the "most powerful place on the Western Front" - as elsewhere, officers and men died and were buried together.

Lt William Noel Hodgson and Lt Travers Adamson

Another officer was 23-year-old Lt William Noel Hodgson, external, who had lived in Gloucestershire and studied at Durham School and Oxford.

Hodgson did not lack bravery - having won the Military Cross for holding a captured trench for 36 hours at the Battle of Loos in 1915 - but he is perhaps best known for a poem called Before Action, written in 1916, in which he appealed to God to give him the courage to die.

"By all the glories of the day / And the cool evening's benison / By that last sunset touch that lay / Upon the hills when day was done," it begins.

The poem was read by Prince Harry at a memorial event on Thursday, ahead of an all-night vigil at the Thiepval Memorial.

Like more than 19,000 British soldiers, Hodgson was killed on 1 July 1916. Many more were wounded, with the British forces suffering 57,470 casualties on a single day in total.

'Lacking experience'

The Army was obviously not made solely of poets and artists like Hodgson and Martin.

Using earthier language, 8th Devons soldier Pte Albert Conn - a former labourer at Millwall Docks who survived the war - described German soldiers of the Prussian Guards as "big ugly bastards" and called the Mametz attack a "balls-up".

Historian Mr Saunders agrees that the attack, which began at 07:27, could have gone better.

The 9th Devons were "lacking experience" and, suffering losses from the machine gun while other British battalions made better progress on either side, they "rather went to bits and were fighting all over the place" rather than as an organised unit, he says.

But he says support from the 8th Devons eventually got through and they reached their objective at 16:30.

Comparing the assault to other parts of the front line - where some units reached their objectives in the morning but others were "mowed down" - Mr Saunders says the Devons achieved a "modest success".

The 8th and 9th Devons - mostly volunteers who joined up early in the war - had gone into battle with more than 1,500 men between them, and by the end of the day more than 400 were wounded, 62 were missing and 236 were dead.

Among those buried in the Devonshire Cemetery - one of 450 now maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in the Somme region - are 10 unidentified soldiers, whose headstones say: "A soldier of the great War. Devonshire Regiment."

The Somme cemeteries, all carefully maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, range from fields of white gravestones to small plots with a handful of graves and single soldiers buried in civilian graveyards.

Together they contain 150,000 British and other Commonwealth servicemen, 50,000 of whom are unidentified.

The Reverend Ernest Crosse (left) with two Devonshire Regiment soldiers in the trenches

The Thiepval Memorial, external to the missing of the Somme, a few miles from Mametz, bears more than 72,000 names.

The fact that most in the Devonshire Cemetery are identified may owe something to the work of their chaplain, Rev Ernest Crosse, who organised a group of stretcher bearers to gather the bodies three days after the attack.

Crosse later said one of the first bodies he saw was that of Capt Martin - the officer who had made the model showing the danger posed by the German machine gun.

The dead Devons were returned to the trench from which they launched their assault.

On a wooden cross there - and now carved in stone - these words were written: "The Devonshires held this trench. The Devonshires hold it still."

The Battle of the Somme

Began on 1 July 1916 and was fought along a 15-mile front near the River Somme in northern France

19,240 British soldiers died on the first day - the bloodiest day in the history of the British army

The British, French and their allies hoped to drive back the German army

The British captured just three square miles of territory on the first day

In total, over a million were killed or wounded on all sides during the five-month battle

Find out more:

- Published23 June 2016