'IS fighter' guilty after trial held partly in secret

- Published

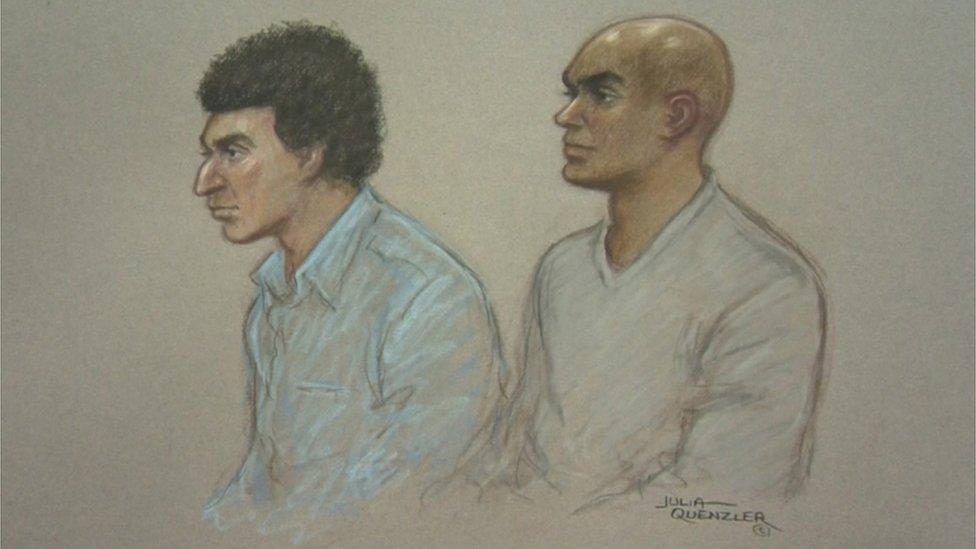

From Left: Gabriel Rasmus, who pleaded guilty, and Anas Abdalla planned to head to Syria

A would-be Syria fighter has been convicted of trying to smuggle himself to the war zone after a semi-secret trial with claims of MI5 harassment.

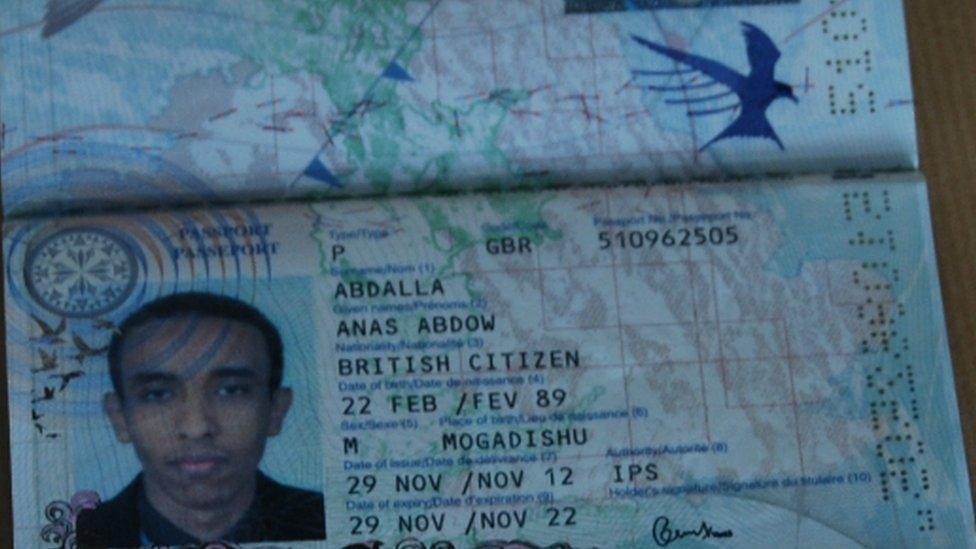

Anas Abdalla had denied preparing for acts of terrorism by hiding in a lorry at Dover with another extremist.

The Birmingham man claimed he was fleeing unwarranted security services intrusion in his life.

At one point, two police officers were instructed by the CPS not to answer questions about MI5 in open court.

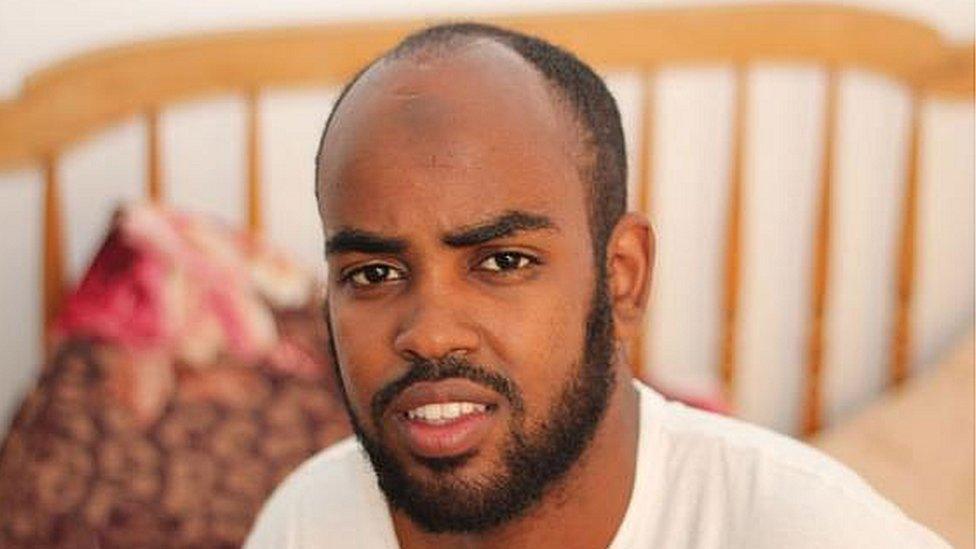

Abdalla was convicted by a majority of 11 to one and will be sentenced at a later date.

As he was taken down to the cells, he threw a plastic cup at a counter-terrorism officer and said: "One day we will be standing in a bigger court than this."

The prosecution, originally scheduled to be a three-week case at the Old Bailey, has taken 18 months to complete with four trials and highly unusual legal arguments over whether or not prosecutors should respond to the allegations levelled against the Security Service.

The men were discovered in a lorry at Dover

Undercover operation

In April 2015 Abdalla, 27 and from the Acocks Green area of Birmingham, was arrested alongside two other men in the back of a lorry in Dover. The prosecution was initially expected to focus on public evidence from an undercover officer that the men had been planning to reach Syria to fight.

Named only as "Mohammed", the officer spent months infiltrating supporters of the self-styled Islamic State group in the West Midlands, including Abdalla and his friend Gabriel Rasmus. Mohammed described both men in court as committed supporters of the self-styled Islamic State, with the means to join it to fight.

Rasmus pleaded guilty to preparing for acts of terrorism while Abdalla and the third man in the lorry, Mahamuud Diini, denied the offence.

But the case became bogged down over whether or not prosecutors would respond to Abdalla's claims that he only wanted to leave the UK because MI5 had made his life a misery.

MI5 meeting

In February 2013, the Somali-born British citizen said detectives "tricked" him into a meeting at a police station with an MI5 officer called "Phil" who allegedly warned that if he did not become an informant his "life will be very difficult".

Over three months of legal clashes during the first two attempts to hold the trial, the defence and prosecution argued over what should be disclosed to the defence and jury about the purported meeting.

Eventually when two West Midlands Police counter-terrorism officers, Detective Constable Brett Bambury and Detective Sergeant Ryan Chambers, appeared in the witness box, both of them said they could "neither confirm nor deny" anything about the alleged meeting, an instruction given to them by the CPS.

What is Neither Confirm Nor Deny (NCND)?

"NCND" is a long-standing government strategy deployed to avoid giving away anything about an agency's operations that, in turn, could lead to guessing games about what else it does.

The stance is adhered to whether or not a claim against intelligence and security agencies is true or not.

Security chiefs believe giving anything away about how MI5 and police recruit informants - or indeed what they don't do - would compromise their sources.

At worst, they fear that revealing a detail about one operation, but not another, would indirectly provide clues about informants to crime and terror networks, endangering lives.

The NCND stance is not unique to the UK. US intelligence chiefs invented the phrase and variations of it are deployed around the world.

Abdalla claimed MI5 harassment had compelled him to try to leave the UK

That triggered further rows with Judge Christopher Moss QC complaining about the "unsatisfactory stance of the Security Services". He gave an undisclosable ruling against the prosecution - who then threatened to pull the entire case unless the Court of Appeal overturned it.

While they won that challenge against the judge, he had to halt the case days later amid more behind-the-scenes arguments.

At the third attempt to hold the trial in April, the same two police officers were instructed to give the same "neither confirm nor deny" answers.

This time, the new trial judge Richard Marks QC told jurors that they must accept the defendant's account as "accurate and reliable" in the absence of any contradictory prosecution evidence.

That jury failed to reach a verdict in the case against Abdalla - but cleared Mahamuud Diini who had said he was trying to go abroad to find his missing brother.

Ahmed Diini, also a close friend of Abdalla, had been banned from the UK in 2011 as a suspected extremist. He had disappeared in Turkey after jumping from the window of an immigration detention centre.

Anas Abdalla told the trial that part of the reason he was scared of the Security Services was that Ahmed Diini had told him that a British intelligence officer had been complicit in his earlier torture in an Egyptian prison.

Ahmed Diini: Last seen in Turkey

As the fourth and final trial approached in August, prosecutors sought permission for "in camera" evidence from an unnamed witness who would specifically respond to Abdalla's police station allegation and his claims of ongoing harassment. The application did not state that there would be a response to the Egypt claims.

Secrecy in trials: What the law says

PII applications: Public Interest Immunity is a legal process through which a minister signs a certificate saying that sensitive material relating to national security cannot feature in a trial. Once approved by a judge, the sensitive information is withdrawn from the case and cannot be used by either the defence or prosecution.

In camera hearings: These are private sessions of a trial where the public and media are banned. The jury hears the evidence but must keep it secret. In camera hearings are very rare.

The Erol Incedal trial: In 2013 journalists were allowed to sit in a closed court to hear some of the secret evidence in the trial of suspected terrorist Erol Incedal. Those journalists are still banned from revealing what they heard.

When this final trial got to the point where the detectives had been asked in the earlier trials what had happened at the police station, the proceedings went behind closed doors.

BBC News cannot report what the jury heard as the media and public were barred. But during Abdalla's later appearance in the witness box, he didn't repeat the allegation that he had been threatened at the police station.

Instead, he said he had left the meeting with MI5 with "a handshake and a smile" - although still refusing to help them.

'Altered stance'

In his ruling explaining why secret evidence would be allowed, Judge Marks said prosecutors had "significantly altered their stance" now that there was only one defendant involved.

While not specifying who the prosecution was calling as a witness, he said the new evidence was "extremely limited" and "highly relevant". He dismissed suggestions from the defence that this "late ambush" amounted to an unfair trial.

"It is eminently preferable and in the interests of justice [if the law allows] for the jury to hear the evidence so that they may be in the best possible informed position so as to be able to reach a conclusion that is fair to both the prosecution and the defence in so far as this critical aspect of the case is concerned," he said in the open ruling.

The judge said that he had been persuaded to allow the secret hearing because of the risk that whatever was said would indirectly compromise the trust that current and future informants place in the Security Services.

"There is a world of difference between, on the one hand, a would-be informant reading/hearing publicly what a defendant has said in open court and, on the other hand, reading/hearing the evidence of any state agent," said the judge.

"The knowledge that having co-operated with a state agency, a witness from that agency had given chapter and verse in open court about the dealings they had had, would in my judgment be highly likely to act as a serious disincentive to others who might otherwise be contemplating rendering assistance."

- Published7 January 2016