Bereavement: How do you help a child cope?

- Published

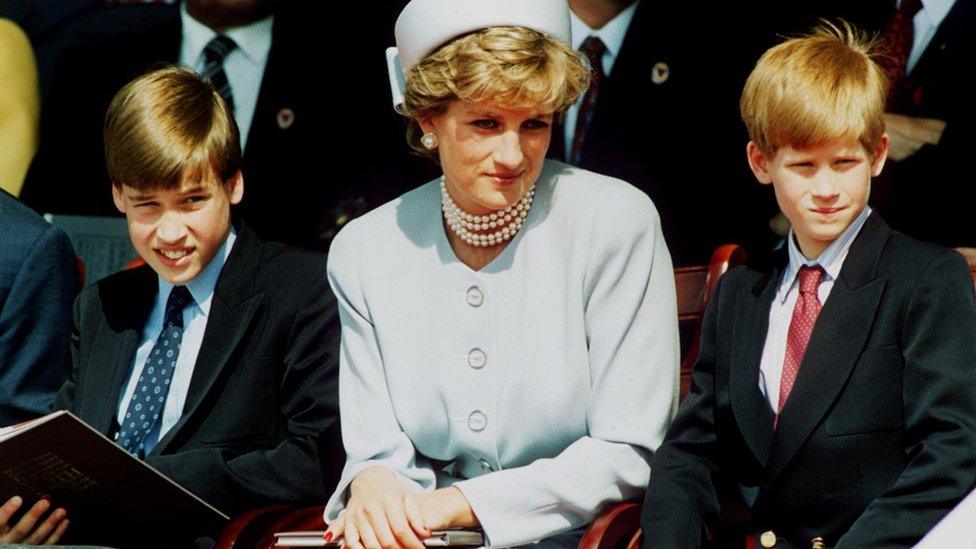

Prince Harry says he regrets not speaking for years about the impact on him of his mother's death in 1997, when he was aged just 12.

So how best can adults help and talk to children about bereavement? Some share their approach with BBC News.

Tracey Unstead, Kingsteignton, Devon

"I lost my husband, Bob, in Sept 2015. He had a terminal (lung) cancer - mesothelioma.

Our now 10-year-old son simply adored his dad, 'me, and mini-me', as they were affectionately known.

As a family we have encouraged Charlie to talk about all aspects of what happened. Using laughter, photos, music, listening, carrying on with his sport, general chit-chat about his dad and most importantly being totally honest, even when the questions being asked are difficult to answer (as emotions are heightened).

Primarily for me it's about being completely honest, about everything. About how everything has changed. You've gone from having two parents to one parent. I have to be mum and dad, guide and support. All singing, all dancing.

We have had to change; emotionally, financially, family dynamics and priorities. We have no choice. The choice is how you deal with it.

Be a realist

It's about listening because there are frustrations there for him that we're unable to do something about, or that I'm going to be finishing work late...

Parents of many bereaved children say 'give them space to talk'

It's about communication, explaining that none of us wanted this. That if a parent is taken away by a car crash or some sort of disease, no-one ever wants that to happen and we have to make the best of everything.

But you've got to be realistic and we were honest from day one.

We explained what cancer was, how it manifests in the body. What happened when his dad died. What a coroner was. Without being scary, to use those words.

He gave me a thank you card the day his dad died, saying 'thank you for helping me understand'.

Funerals as a celebration

Funerals are very dark but we made his dad's as if it was a birthday party - with his favourite biscuits, his favourite music. So that, when Charlie grows up, he will think 'this was the day my dad was buried, and actually, it was a sad day, but we had a party'.

I cry in front of him and I'm sad and we say we miss daddy. I acknowledge it. But he's a child. They're sometimes more resilient.

He's 10. He needs to laugh, have fun, get into mischief.

Harry, (right) with his mother and Prince William, didn't speak about the effect of her death until three years ago

Charlie has two grown-up sisters, so we have been able to do this as a family. His school has played a huge part, which I believe has helped Charlie enormously. A school that is empathetic and understanding to such difficult personal times in a child's life, for me, was a godsend.

Harry's silence

I was horrified to hear from Prince Harry that he didn't speak about the effect of his mum's death until three years ago. I can't imagine how that must have felt.

That goes on with every child who has lost a parent. There will be children today who will be sat down and told that awful news, and their lives will change forever.

If Charlie can grow up to be as funny and hard-working as his dad was, with the knowledge we rallied round him and supported him, that's a good job done.

He's a remarkable young man, his father would be extremely proud of him, as we are.

John, from Surrey

"Our children were 11 and 13 when their mother died in 1985 - a time when bereavement support was scant.

I was offered none and didn't even know that any was there. There wasn't the internet then. Now, there are so many more places to find help.

My one and only mission in life became bringing up our children. So, I thought I had to look forward and not back.

The result was that I erased many happy memories of my wife in order not to become maudlin, self-pitying and useless to my children.

This didn't make me a better father - in fact probably a worse one - as we spoke very little about their mother and still don't, more than 30 years on.

Kissed 'six times a year'

Talking and recalling wonderful memories are not weaknesses, they are strengths and, though I did what I did with the best of intentions, it was neither best for our children nor for me. I had to work out what to do alone: my mother was already dead, my father was in his 70s.

He was very old-fashioned, very stiff upper lip. He said to me one day, 'Your mother came from a kissy, feely family. But I came from a family where I got kissed six times a year, once on my way to school at the beginning of term and once on my way back home at the end of term'.

Close but silent

My wife's cancer started off as breast cancer but a secondary cancer set in and that was that.

Once I knew she was dying, I told our children. I will never know the extent to which that sank in.

It affected both of my children very differently. The elder one dived into studies and got a good degree. The younger one walked away from studies completely.

We're close but we still don't talk about it.

I would say to any parent whose child is bereaved to talk about it, ask for help, do anything you can but don't keep quiet.

'Isabel', from Grampian

"We lost my daughter's father to suicide when she was three. She's 18 now.

She understood what had happened very well because her dad was in hospital for some time. She was able to go in and see him, I was able to prepare her for what was happening.

She attended his funeral. We spoke whenever she wanted to about him.

She missed him and misses him at so many stages of her life and always will. There's lots of different points in childhood - even just for things like learning to ride your bike.

She has a more mature sense of understanding, but it's still a sense of loss now as it was then.

When she was 13 she felt as if nobody else had grown up without their father being alive. I wanted her to meet other kids who had gone through similar experiences. Through research, I came across a bereavement camp in America. It was a safe place for kids to come together, grieve, remember and have fun.

She left camp emotional but saying 'no offence mum, but they knew what I was talking about'. Music to my ears and I shall be forever grateful. Camp helped my daughter to feel like she was in the majority and not the minority.

I would say (to parents of bereaved children) to keep lines of communication open. Expect that they are going to bring it up at the most unexpected time. They may appear to be not thinking about it. But they are just processing it and trying to get on with their everyday lives."