Inside the secret world of explosives forensics

- Published

Blink and you miss the turning. There are no signs to announce its whereabouts, just a leafy lane in rural Kent that ends with a chain-link fence, a gate guarded by police and a visitors' reception.

The UK government's Forensic Explosive Laboratories (FEL) at Fort Halstead is clearly not a place that likes to advertise.

Yet here, in this sprawling collection of red-brick MOD buildings, pristine laboratories and curious ventilation chimneys, close to 2,000 pieces of evidence are brought in for forensic examination every year.

When the Pan Am jumbo was brought down over Lockerbie in 1988, parts of the shattered fuselage were transported here to Fort Halstead for analysis.

So too were fragments of the 7/7 London bombs in 2005 and the failed devices that fizzled but did not explode two weeks later.

Debris ranging from the IRA bombings to the Bali blasts of 2002, to an improvised homemade firework ends up on the examination tables, frequently resulting in the scientists' conclusions being used in court.

If they had a mantra, it might well be "from fireworks to fuselages".

Every single criminal or terrorism case that involves explosives, either in Great Britain or involving British nationals overseas, pulls in the expertise of Fort Halstead's white-coated scientists and investigators.

Parts of the Pan Am jumbo's shattered fuselage were transported to FEL

Funded by the Home Office but employed by the MOD's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL), they primarily serve two customers: the Office of Security and Counter Terrorism (OSCT) in Whitehall and as an impartial laboratory for the criminal justice system.

"We process around 200 cases a year," says Richard Biers, one of the DSTL scientists. "In many ways, what we do here is unique. We are the only forensic lab dedicated to explosives in Great Britain. There is nowhere else in the world with quite the same level of specialisation on explosives for as long as FEL." (It has existed since the 1870s).

So what do the 30 scientists and case officers and the dozen or so support staff actually do at Fort Halstead?

There are three basic scenarios, they explain, which all call for their expertise; an explosion has gone off, a device has been made safe or potential bomb-making materials have been found.

Within 60 minutes of any of the above taking place, either the on-call team will need to be ready to receive samples or a police car will rush them straight to the scene.

The police have a list of on-call numbers while duty case officers at Fort Halstead keep their mobiles switched on day and night.

Typically, the on-call team will be one senior officer with at least four years experience who may have to give his or her expert opinion in court, accompanied by one junior officer.

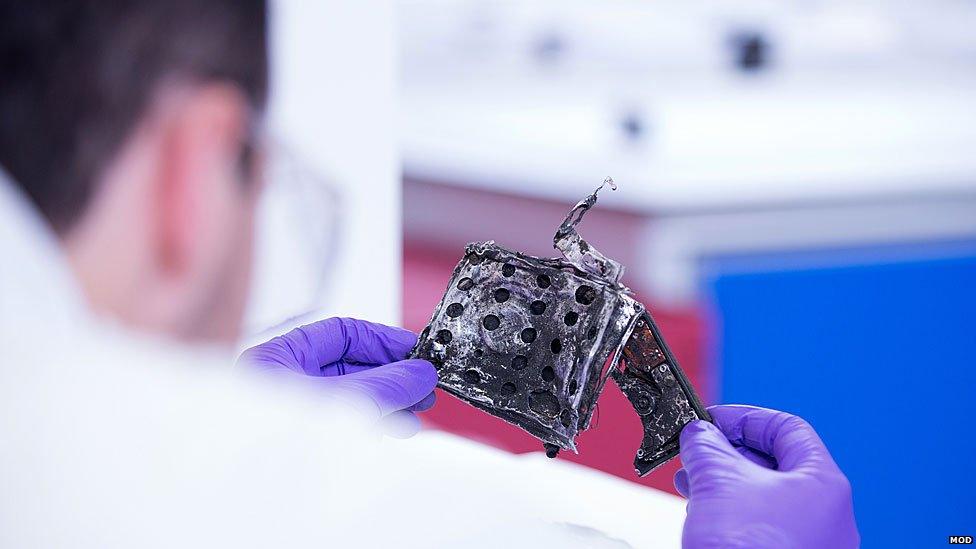

Painstaking examinations and detailed notes are made so that evidence can be used in court

FEL also provide forensic kits to the police who are the first to arrive on the scene. Known as a Terk - a Trace Explosives Recovery Kit - it contains a swabbing kit with enough cotton wool and solvent to send up to six samples back to Fort Halstead for analysis.

"The first thing after the police photographers have done their work is the trace work," explains the Principal Forensic Investigator, (who asks not to be named), referring to the microscopic particles invisible to the naked eye.

Incredibly, these can be as small as one billionth of a gram - the laboratories can detect levels 100,000 times less than a single grain of sugar.

Inevitably, this brings its own set of challenges. If there were even the minutest risk of evidence being contaminated by traces of explosives already in the lab then their work would be invalid.

To ensure this can't happen the labs use filters, scrubbed surfaces and a system known as "positive pressure" that pumps air out and prevents particles drifting in.

"Our job," says Biers, "is to determine if explosive material was involved. If it was, then what was it and could it cause harm? Is it linked to any previous incidents or does it contain new technology we need to be aware of?'

So what kind of person works here, I ask, in this place that most people don't even know exists?

"Chemists, mostly," says the Principal Forensic Investigator. "Also graduates with degrees in electronics, forensics and science masters. We then take two years to train them here at Fort Halstead and a further two years as a forensic analyst, going to crime scenes as a junior officer and learning how to come across effectively in court."

There can be a great impetus to find the evidence, she says, when there is a live investigation going on. "But then there are months afterwards of painstaking examinations and detailed notes so that evidence can be used in court."

FEL scientists examined evidence following the assassination of Benazir Bhutto

As we leave the aseptic world of the labs at Fort Halstead, with their white coats, purple gloves and faint whiff of chemicals, I notice photographs up on the corridor wall depicting some of the recent terrorism cases on which the team has worked.

Not all of them are in Britain. Beneath the heading "Operation Memini" is one of the last photographs of the assassinated Pakistani politician Benazir Bhutto.

The text reads: "FEL assistance to SO15 (Counter Terrorism Command) into cause of death of Benazir Bhutto, Rawalpindi, 2007".

The photo shows a smiling Ms Bhutto standing up through the roof escape hatch of her car, greeting her supporters, moments before she was killed.

After the Pakistani Government asked for the UK's help, the Fort Halstead investigators travelled to Rawalpindi as part of the team led by the Met Police Counter Terrorism Command.

The FEL scientists pored over the evidence and their analysis was included in the report which found that she was killed by an explosion that caused her to have a fatal impact with the roof escape hatch.

Isn't there a risk, I suggest, that you will be asked to provide evidence that supports a prosecution's case, whether it's here or overseas?

"Emphatically not," replies Biers. "The thing we guard most dearly is our total impartiality. We're here to serve the needs of justice and to go where the evidence takes us."

You can hear Frank Gardner's report on the UK government's Forensic Explosive Laboratories on the PM Programme on Thursday 11 August and afterwards on BBC iPlayer.