Bishop David Jenkins obituary: A controversial cleric

- Published

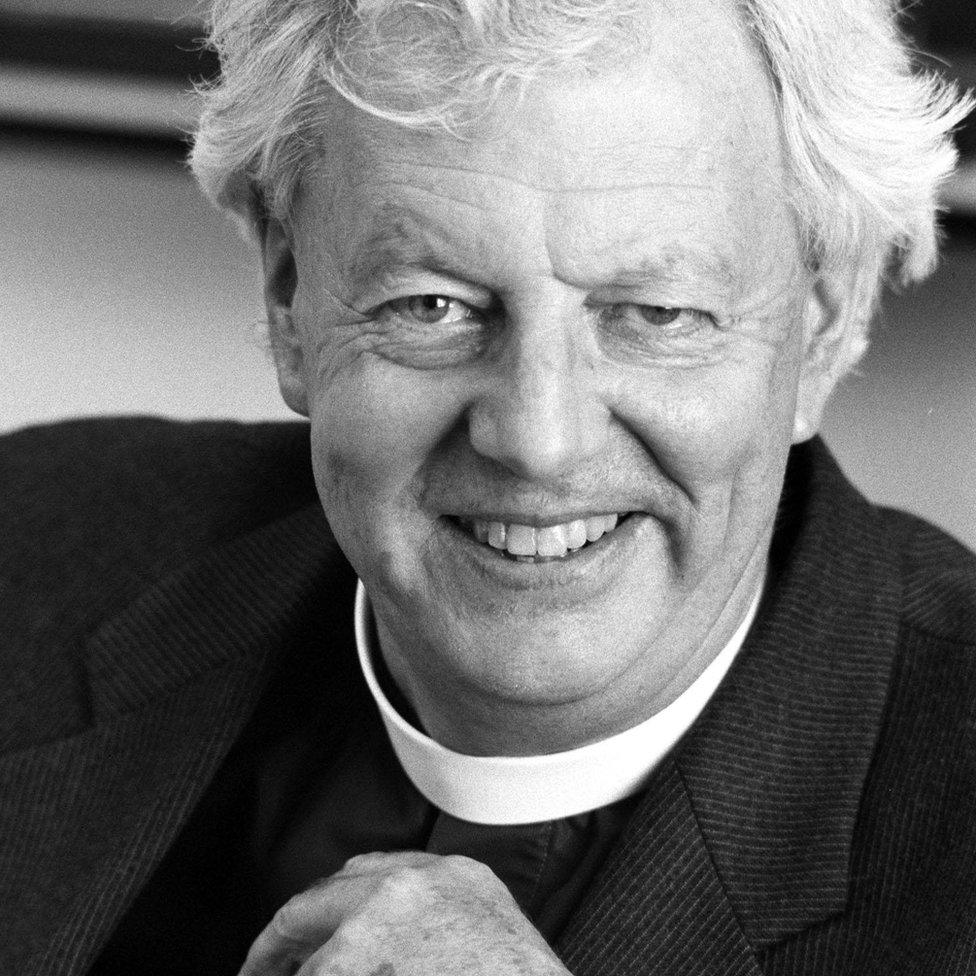

David Jenkins was an Anglican bishop who questioned some of the fundamental beliefs of Christianity.

His views on the virgin birth and the resurrection caused a storm of protest and considerable opposition to his appointment as Bishop of Durham.

His forays into the field of politics saw attacks on both Conservative and Labour administrations for what he saw was their over-reliance on market forces.

An academic theologian, rather than a parish priest, he became for many, the symbol of modernisation and liberal ideas in the established church.

David Edward Jenkins was born on 26 January 1925 in Bromley, Kent, and brought up in a Methodist family.

Confirmed into the Church of England as a teenager, his education was disrupted by World War Two. He was commissioned in the Royal Artillery and ended the war in India.

On his return to civilian life, he took up a scholarship to Queen's College Oxford, graduating in 1954. He studied at Lincoln Theological College before his ordination by the Bishop of Birmingham, and served for a brief period as a curate in Birmingham Cathedral.

He was never to become a parish priest, something his future opponents took delight in pointing out. Instead, he took on a series of academic and administrative posts including a spell with the World Council of Churches in Geneva before returning to his old Oxford college where he served as chaplain and lectured in theology.

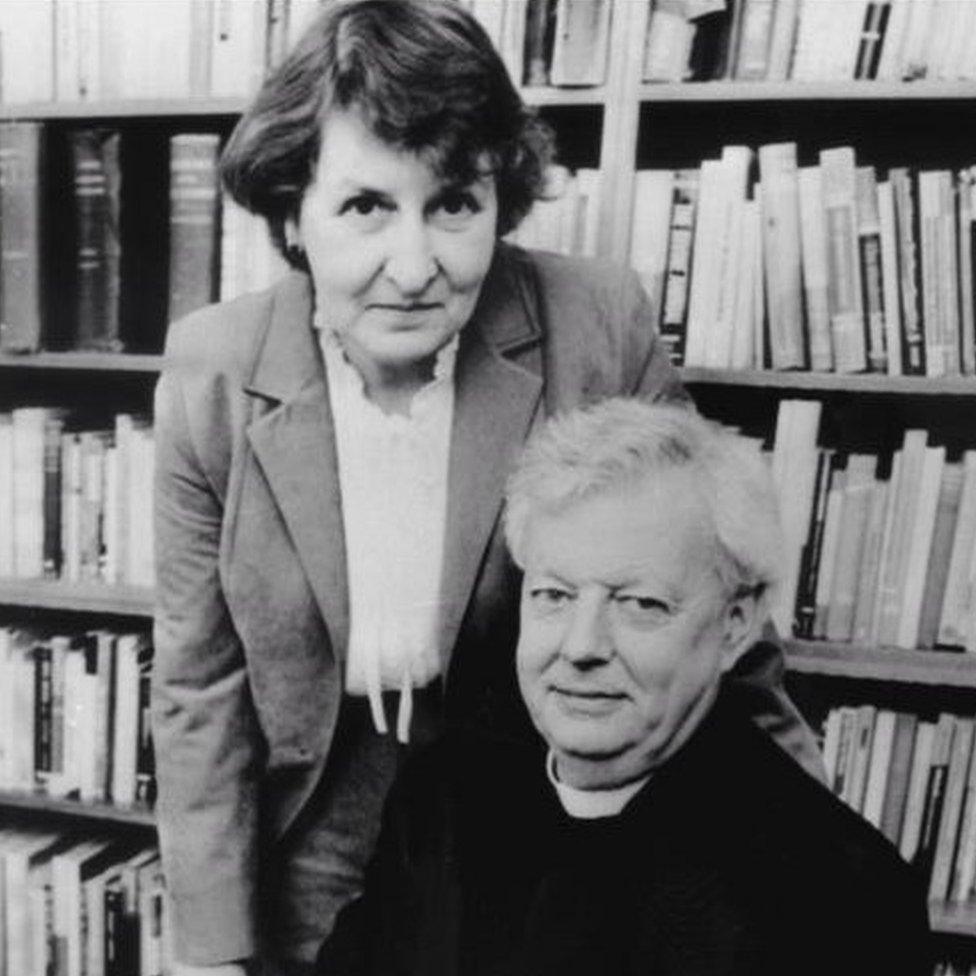

His wife Molly was a constant source of support until her death in 2008

He was professor of theology at Leeds University when Mrs Thatcher recommended his appointment as Bishop of Durham in succession to Dr John Habgood, who had become Archbishop of York.

In April 1984, shortly after his appointment, David Jenkins said on ITV's Credo programme that the story of the virgin birth had been added later by early Christians to express their faith in Jesus as the Messiah.

"I wouldn't put it past God to arrange a virgin birth if he wanted, but I very much doubt he would," he said.

He also said that the resurrection was not a single event, but a series of experiences that gradually convinced people that Jesus's life, power, purpose and personality were actually continuing.

Intellectual limitations

He caused more outrage a month later when he said there was absolutely no certainty in the New Testament about anything of importance. Widespread doubts were expressed about the wisdom of making him a bishop, and a petition with more than 12,000 signatures was delivered to the Archbishop of York. Neither he nor the Archbishop of Canterbury apparently doubted Jenkins's suitability.

The consecration in York Minster was interrupted twice by protesters. Two days after the service, the Minster was struck by lightning and badly damaged by fire - an event some Christians believed to be a warning from God.

He later joked that the Almighty had missed the target. "God was probably aiming at the General Synod, but he missed even that."

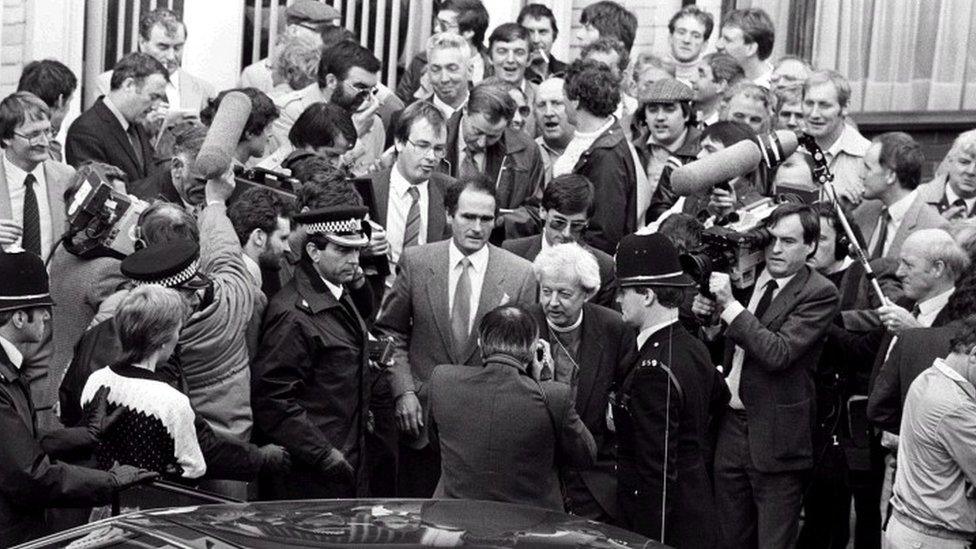

At his enthronement in Durham Cathedral in September, when the miners' strike was some months old, Dr Jenkins called for the replacement of coal boss Ian MacGregor - "an imported elderly American" - and the scaling down of NUM leader Arthur Scargill's demands. Later, he was to advise the miners that they had lost and should go back to work.

He took an active role in trying to mediate in the 1984 miners' strike

He made no secret of his loathing for the Conservative government and regularly urged ministers to intervene in the decline of industry in his diocese in North-East England.

The then party chairman, John Selwyn Gummer, who was also a member of the Church of England Synod, was one of his strongest critics, and Lord Hailsham, in a bitter attack after the 1987 election, referred to Dr Jenkins's intellectual limitations.

Margaret Thatcher seemed to take a more sanguine view, once remarking after Dr Jenkins and another bishop had criticised the government, that it wouldn't be spring without the voice of the occasional cuckoo.

Jenkins's term as bishop coincided with the split between the liberal and traditionalist wings of the Church. He said of his unorthodox approach to some questions of theology that he hadn't been the only cleric to express such concerns - but that he'd expected more support from the higher ranks of the Church.

Disaster

He faced his critics at the General Synod in York, and won an ovation. Nevertheless, his beliefs continued to cause distress and concern to many in the Church.

He remains one of the few bishops ever to be immortalised on the satirical puppet show, Spitting Image. In one episode, his caricature appears with that of Dr Robert Runcie, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, and persuades God to become an atheist.

Tony Blair, just days before he was elected Labour leader in 1994, addressed the congregation at Dr Jenkins' retirement service in Durham Cathedral - praising the bishop's "honesty, humanity and integrity".

Those who hoped he would disappear into quiet retirement were disappointed. In a 2003 BBC interview, he opined that the Church of England had suffered for being the established Church.

Few doubted his sincerity

"To have an (Anglican) established church, it's necessary for Islam to be an Islamic state, to have Judaism ruled by ultra-orthodox rather than more secularised sharing people. It's a disaster."

Two years later, Jenkins became one of the first churchmen to bless a civil ceremony between two gay men, one of whom was a Church of England priest.

It is doubtful whether the majority of lay people fully understood what David Jenkins's beliefs actually were, but very few could doubt the sincerity and passion with which he delivered them.

He was a cleric who believed the church had to break free of dogma if it was to retain a place in the modern world.