Naloxone: 'Heroin antidote saved my life'

- Published

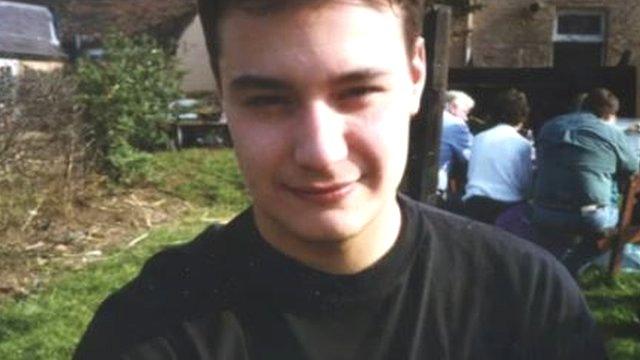

Karl Price has been saved from dying of an overdose by naloxone on three occasions

It has been a year since a change in UK law made it legal for a heroin antidote to be given by anyone who might encounter someone dying of an overdose.

The antidote, naloxone, can be given by friends and family members of addicts - and even their children. It has reportedly saved hundreds of lives.

But does the opioid blocker make heroin addicts feel it is safer to use heroin more often?

Karl Price was just nine-years-old when his 12-year-old brother started using heroin.

Growing up in Birmingham surrounded by the drug, it seemed inevitable that later he too would succumb.

"One day I was in a block of flats, and a guy offered me some, and I said yeah," he tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme. "I was 18."

"Within three weeks of taking it for the first time. I was completely hooked and homeless."

The vigilantes who attack heroin addicts

The next four years of Karl's life were a combination of addiction and crime, focused only on feeding the cost of a habit that sometimes ran to "hundreds of pounds a day".

The drug ravaged his life.

He saw his ex-partner die of an overdose.

And on three occasions he came to the brink of dying too, but was saved each time by naloxone.

The single injection of the antidote works by disabling the opiate receptors in the body, blocking the effects of heroin.

It is an intra-muscular injection, meaning it can be injected straight into a person's arm or leg.

Naloxone was used to treat the singer Prince when he overdosed on opiate painkillers on an earlier occasion before he died.

Despite still being a prescription-only drug in the UK, since October 2015 it has been legal for trained carers, hostel managers, drug users, and addicts' friends and family to carry naloxone in case of an emergency.

Even some toilet attendants and lifeguards, who may encounter accidental overdoses or intentional suicide attempts on the beach, have been trained to administer the antidote.

Training children

Stacey Smith, from the drug charity Change, Grow, Live, runs a scheme that has trained 6,000 people to use naloxone in the past year, saving 241 lives so far.

"It sounds scary to have to inject someone, but it's really simple. It takes 10 minutes to train someone," Stacey says.

When it comes to training children, for example those whose parents are heroin addicts, careful consideration is given on a case-by-case basis.

"It sounds quite horrible, a child injecting a parent to stop them dying," she points out.

"But the alternative might be that they see their parent die. That's the reality of it."

The increased availability of naloxone in the UK comes at a time when more people than ever are dying from heroin and morphine overdoses.

Figures released this month, external by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that deaths from overdoses in England and Wales more than doubled in the past three years - from 579 in 2012 to 1,201 in 2015.

ONS researcher Vanessa Fearn says that this has been partly driven by a rise in the purity of heroin and its wider availability over the past three years.

"Age is also a factor in the record levels of drug deaths, as heroin users are getting older and they often have other conditions, such as lung disease and hepatitis, that make them particularly vulnerable," says Vanessa.

In the US, which is in the clutches of a heroin and opioid epidemic, external, naloxone is reported to have saved 27,000 lives, external between 1996 and 2014.

But its use has sparked a debate, with critics arguing that by reducing the risk of overdose, the problem of addiction is perpetuated rather than eradicated.

It is true that naloxone does nothing on its own to cure addiction.

In the case of Prince, he was revived by naloxone from an overdose of the opiate painkiller called Percocet.

But six days later he died of an overdose of another opiate painkiller, fentanyl, when no one was around to administer naloxone.

'Last resort'

Does an antidote make heroin addicts feel it is safe to use more of the opiate, potentially put them off seeking help with recovery?

Stacey Smith says no.

"Drug users will always take risks because of their habit. Nobody plans to overdose," she explains.

"This kit is a last resort, but of course it's part of a whole approach that includes advising drug users on injecting safely and trying to get them into treatment."

Karl Price agrees, saying safety is not a consideration that even enters an addict's head.

On one occasion, he was given the naloxone injection by a friend when he overdosed in a 10p public toilet - a terrifying experience for both of them.

Drug treatment services hope to introduce a naloxone nasal spray, which is already in use in the US

"Having a naloxone injection is not a pleasant experience. It takes all the drugs out, so you go into instant withdrawal," he says.

"I can remember coming round and feeling really ill - cold, shivering, aching.

"But without it I would have died. I've been so lucky, and I think that can give you that moment of realisation to get help," he explains.

Now 12 months clean, and working as a recovery coach for other drug users for CGL, which has services all over the UK, external, Karl has trained to use naloxone and is encouraging others to do the same.

"Not that many people, even drug users, are aware of it," he says.

"And at the end of the day, if you've got an antidote to something - does anybody really need to die from a heroin overdose?"

The Victoria Derbyshire programme is broadcast on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News channel.

- Published7 November 2015