New approaches to gentrification

- Published

Can gentrified urban areas retain their diversity and vibrancy? Or is there a danger that in the latter stages of gentrification these places become the preserve of the very wealthy, losing much of their original character in the process?

Last November my producer and I went to San Francisco to make a programme about Silicon Valley. One afternoon I took him to the city's Mission district. This is a famously vibrant Latino neighbourhood and I wanted to show him the burrito joints, cool thrift stores and bars playing salsa that I remembered from my previous trips to the city.

What we found shocked me. We cycled through quiet street after quiet street. The bars I remembered had been turned into luxury apartments. The thrift stores had gone. And instead, there was just the occasional minimalist cafe serving flat whites and expensive "artisanal" brownies. Mission had been gentrified.

Gentrification is a powerful force and it often does a lot of good. An area that is run-down really benefits from the influx of new, often young and creative, types, who renovate dilapidated property, open shops and set up new businesses, providing employment and possibilities for the people who live there. It boosts the diversity of an area and provides real economic growth.

But it is also comes with costs. A smarter area means higher rents and soon both the original inhabitants of an area - and those new, creative incomers - have to move out.

And they're replaced by a new, wealthier wave of incomers who are less keen on the funky bars and all-night convenience stores and prefer instead to live in gated apartment blocks, doing online shopping and getting food delivered.

Areas like parts of Brixton in south London have been transformed by gentrification

They campaign for local nightclubs to be shut down. They complain about the edginess of the street in which they live. And the result is a part of town that is bland, soulless and sanitised. This is what has happened to Mission and it's a terrible shame.

So how can we stop this dull third stage of gentrification happening? To find out, Peter and I set off on a journey around the UK to what can be done to freeze gentrification in its interesting, diverse and economically vibrant phase. The result is an edition of Analysis on Radio 4.

Almost everyone we spoke to agreed that the early stages of gentrification benefited an area. The diverse mix of existing and new residents create a vibe on the street that benefits both groups.

Loretta Lees, an academic who has spent much of her career studying gentrification, argued that interacting with people from different social groups, ethnicities and backgrounds was good for democracy.

And the US researcher Richard Florida showed us data that proves that diversity leads to economic success. All those new shops and businesses bring employment and money into the neighbourhood. And streets that had previously been depressed and run-down become attractive places to walk along, meet friends and spend your day.

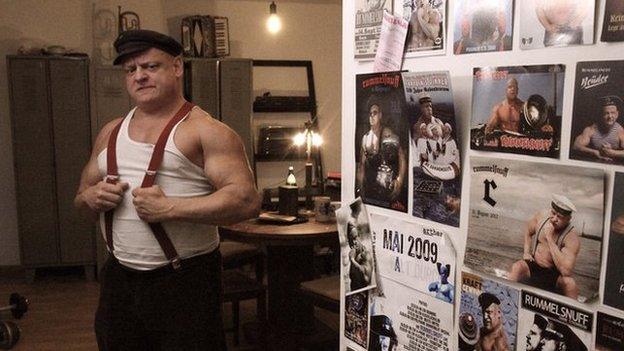

There have been tensions over gentrification in Berlin

Let the free market roll on though and landlords and developers will, reasonably enough, be on the lookout for greater returns on their investment - and that new wave of wealthier residents will provide it.

Some cities, like Berlin, have used regulations to try to stop the free market in its tracks. There, in some parts of the city, you need permission to install marble ceilings or a second bathroom in your property in case the new higher rent forces people out and changes the demography of an area.

Councils in the UK have similar, though less specific, rules designed to maintain a mix of people and housing in their neighbourhoods.

But regulations often have unintended consequences and it was the solutions that used the free market, rather than tried to stop it, that impressed us most. And those are already happening in the private sector.

Right now, interest rates are low and big investors, like pension funds, are looking for new ways of guaranteeing solid and predictable returns. The result is a new wave of developer who is building housing not for a quick sale but for rent.

In September 2015, anti-gentrification activists attacked the the Cereal Killer Cafe in east London

One of these is Grainger, which has built a block of 100 one, two and three-bedroom flats in Barking in east London. The building is more like one of those cool hotels in which you stay in places like Oslo or Barcelona.

There's a big reception area with sofas, books and a small kitchen. The building has a 24-hour gym for residents. And, because the tenants are mostly on three-year contracts, they look after the fabric of the building better than people who come and go more often.

In the UK, we're suspicious of renting. We tend to feel we haven't made it unless we have our foot on the property ladder. But projects like Grainger's show that renting can be as fulfilling and rewarding as owning.

Already the residents in the block in Barking have formed a community. They organise social events and classes in the building's common parts and their landlord has a real stake in ensuring the area remains vibrant and diverse.

Developers as renters isn't the only solution to the potential downside of gentrification. But it's one, I think, that uses the free market to everyone's advantage. And in the UK, that means it's a proposition that could have a real chance of success.

- Published2 January 2016

- Published27 June 2012

- Published27 September 2015