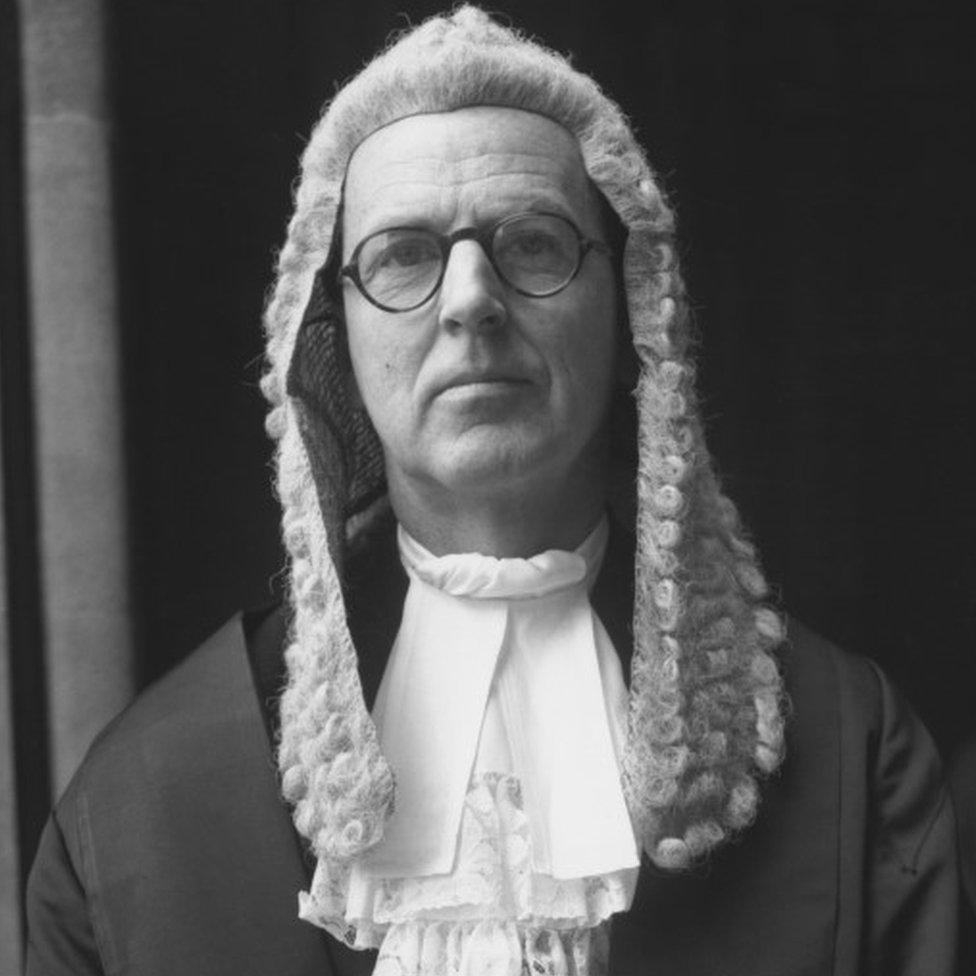

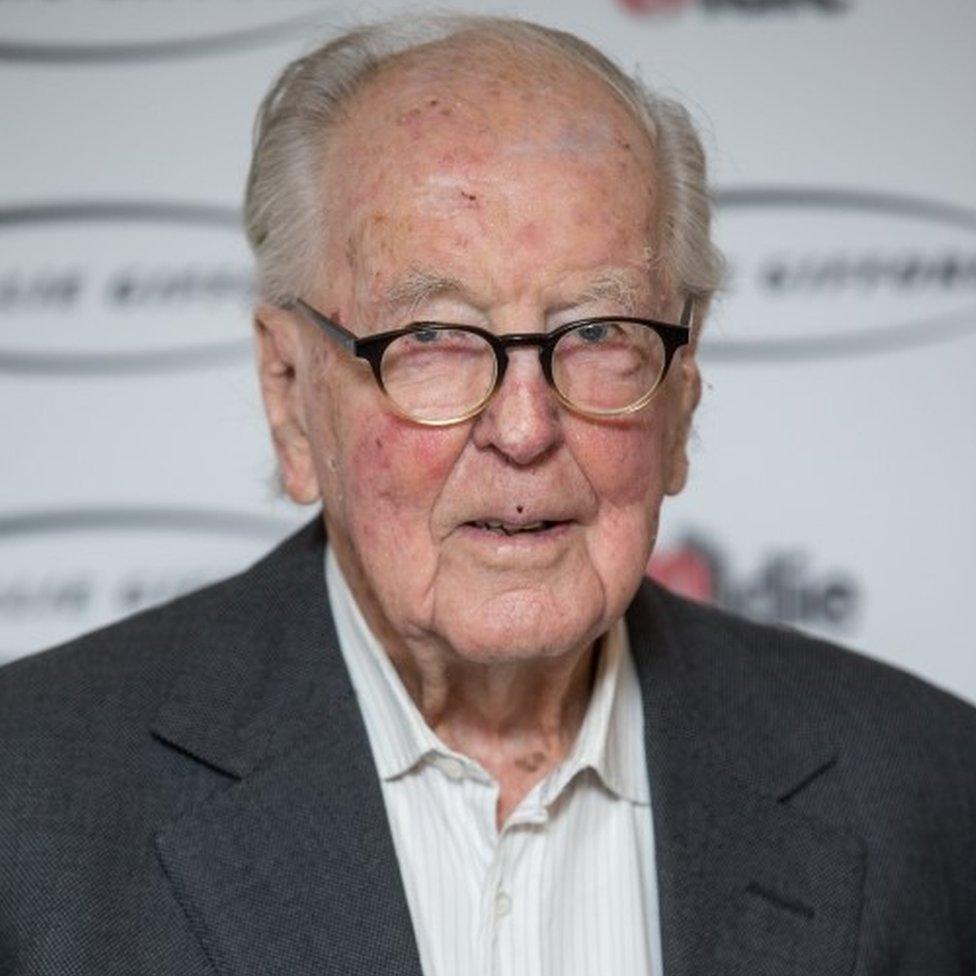

Obituary: Jeremy Hutchinson QC dies at 102

- Published

Jeremy Hutchinson, who has died at the age of 102, gained a reputation as one of the greatest advocates of his time.

He made his reputation in high-profile obscenity trials from an era when the Establishment was under attack from a more liberal social order.

He was on the team that defended the publishers of Lady Chatterley's Lover - other clients included Christine Keeler and Soviet spy George Blake.

He was the model for John Mortimer's character Rumpole of the Bailey.

Jeremy Nicolas Hutchinson was born in London on 28 March 1915, the son of a noted barrister, St John Hutchinson KC, and his wife Mary Barnes. Both were active members of the literary Bloomsbury set, counting writers such as TS Eliot and Aldous Huxley as friends. His mother became the model for Virginia Woolf's Mrs Dalloway and had a long affair with Woolf's brother-in-law, Clive Bell.

He underwent a solid middle-class education at Stowe School before going to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he read philosophy, politics and economics, a degree that was then referred to as modern greats.

Called to the Bar in 1939, his career was interrupted by the outbreak of World War Two and he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

He made his name during the social revolution of the 1960s

In 1940 he married the actress Peggy Ashcroft, seven years his senior, after a whirlwind courtship that started when he talked his way into her dressing room in a Brighton theatre.

He put this success down to his naval uniform, "the only time in my life when I looked really attractive", and the couple were married six months later.

A year later he was floating in the sea off Crete after his ship, the destroyer HMS Kelly, was sunk by a German bomber. Hutchinson and his dashing skipper, Lord Louis Mountbatten, clung to a life raft and sang songs to keep up their spirits.

A man of impeccable liberal credentials, Hutchinson became a Labour candidate in the 1945 general election, encouraged by an Admiralty decision to give an extra month's leave to anyone who stood for Parliament.

'Women more sensible'

He took on the safe Conservative seat of Westminster, which contained 10 Downing Street, and recalled knocking on the door in a bid to canvass the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. The great man was away but Hutchinson cheerfully gave a speech to his staff. His driver on that occasion was a young firebrand named Tony Benn.

After his inevitable defeat he turned his attention to carving out a career at the criminal Bar where he was able to bring to bear his liberal outlook and his passion for social reform.

A man seemingly possessed of amazing good luck, he financed his early legal career by selling a valuable Monet painting he had inherited.

Hutchinson admitted he found Christine Keeler rather dull

In 1960, he was part of the team that defended Penguin Books after it published DH Lawrence's novel Lady Chatterley's Lover. Hutchinson had cannily pushed for as many women jurors as he could get.

"I've always taken the view that women are much more sensible about sex," he later said. "Men get so worked up about it."

The trial was notable for the comment by Mervyn Griffiths-Jones, the QC leading for the Crown, who asked the jury, "Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?" The remark merely underlined the yawning gap between the Establishment and the rest of society. Penguin was acquitted and sales of the book soared.

Appointed a QC in 1961, Hutchinson gained a reputation for taking on high-profile clients. He represented Christine Keeler during her trial for perjury following the scandal of the Profumo affair in 1963. He later confessed he found her rather dull.

Sympathetic

He also appeared for the Great Train robber Charles Wilson and for the Soviet spy George Blake. Hutchinson said he was moved to appear for Blake after being impressed by what was described as Blake's "semi-religious" conversion to communism.

Blake was sentenced to 42 years, a sentence Hutchinson described as "monstrous" and he later admitted being delighted when Blake was sprung from Wormwood Scrubs prison in 1966.

"Even better, it turned out to be a totally amateur job organised by two of my clients in Wormwood Scrubs on a short sentence."

In the social and sexual revolution of the 1960s, some obscenity trials were descending into farce. While Hutchinson denied he ever tried to get a case laughed out of court, he could never resist pricking the pomposity of judges who seemed far removed from everyday life. His habit of referring to the figure on the bench as "old darling" was reprised by Horace Rumpole in the John Mortimer novels.

He confessed to being delighted when Soviet spy George Blake was sprung from prison

In 1966 Hutchinson's marriage to Peggy Ashcroft ended and he married a former nurse, June Osborn.

Hutchinson defended Paul Ableman's historical treatise, The Mouth and Oral Sex, in a 1969 trial on charges of obscenity. The judge, Mr Justice King-Hamilton, asked the writer Margaret Drabble, one of the defence witnesses, why anyone needed to read about oral sex: "We have managed to get on for a couple of thousand years without it."

In his closing speech to the jury, Hutchinson was sympathetic. "Poor His Lordship! Poor, poor His Lordship! Gone without oral sex for 1,000 years."

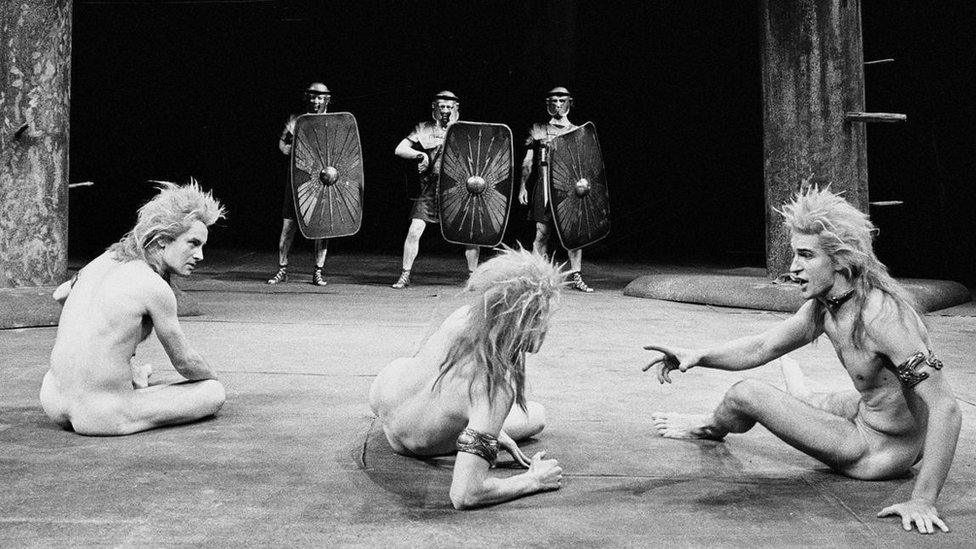

Hutchinson was briefed for the defence in 1982 when the moral campaigner Mary Whitehouse brought a private prosecution against the director of the National Theatre's production of Howard Brenton's play The Romans in Britain. The prosecution held that the director had "procured" an act of "gross indecency" between two actors who played a scene in which a Roman soldier had anal sex with a druid.

Self-confidence

A witness who had been sitting in the upper circle claimed to have seen an erect penis, but Hutchinson, during a speech which produced hilarity in court, demonstrated that the actor had been wriggling his thumb.

He later defended the drug smuggler Howard Marks - "he was great fun" - and also the journalist Duncan Campbell in the 1978 trial following the leaking of official secrets from GCHQ, in which Hutchinson first exposed the practice of jury-vetting.

Away from the court, Hutchinson was a leading light in the move to establish Tate Liverpool, using the wide range of friends and contacts that his gregarious nature had built up over the decades.

The Establishment man who took on the Establishment

He was created a Labour peer in 1978 but became the first to resign his seat in the Lords after deciding he was getting too old.

Jeremy Hutchinson's success was based on a mixture of supreme self-confidence and great legal acumen coupled with his strongly held opposition to what he saw as the small-minded Establishment.

Yet the great irony in Hutchinson's life was that he was a fully paid-up member of the Establishment he gently mocked in his closing speeches.

His greatest gift was his genuine empathy with many of the men and women he defended. "My colleagues used to say, 'Hutchinson, you adore your clients.' But it was hard not to. You meet such extraordinary people. They were rather lovable."

- Published14 November 2017