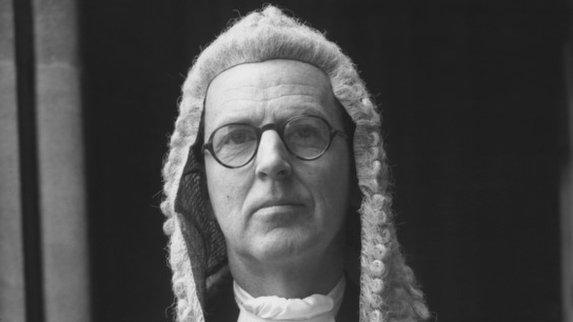

The QC, Lady Chatterley and nude Romans

- Published

Jeremy Hutchinson, who has died aged 102, was one of the greatest advocates of the 20th century.

A poetry-loving socialite, he acted for a number of high profile clients in trials that both mirrored and questioned the changing attitudes in British society during the 1960s and 70s. A man of immense charm, and a great love of the underdog, he became the template for John Mortimer's famous creation, Rumpole of the Bailey. These are just three of the trials that made his name.

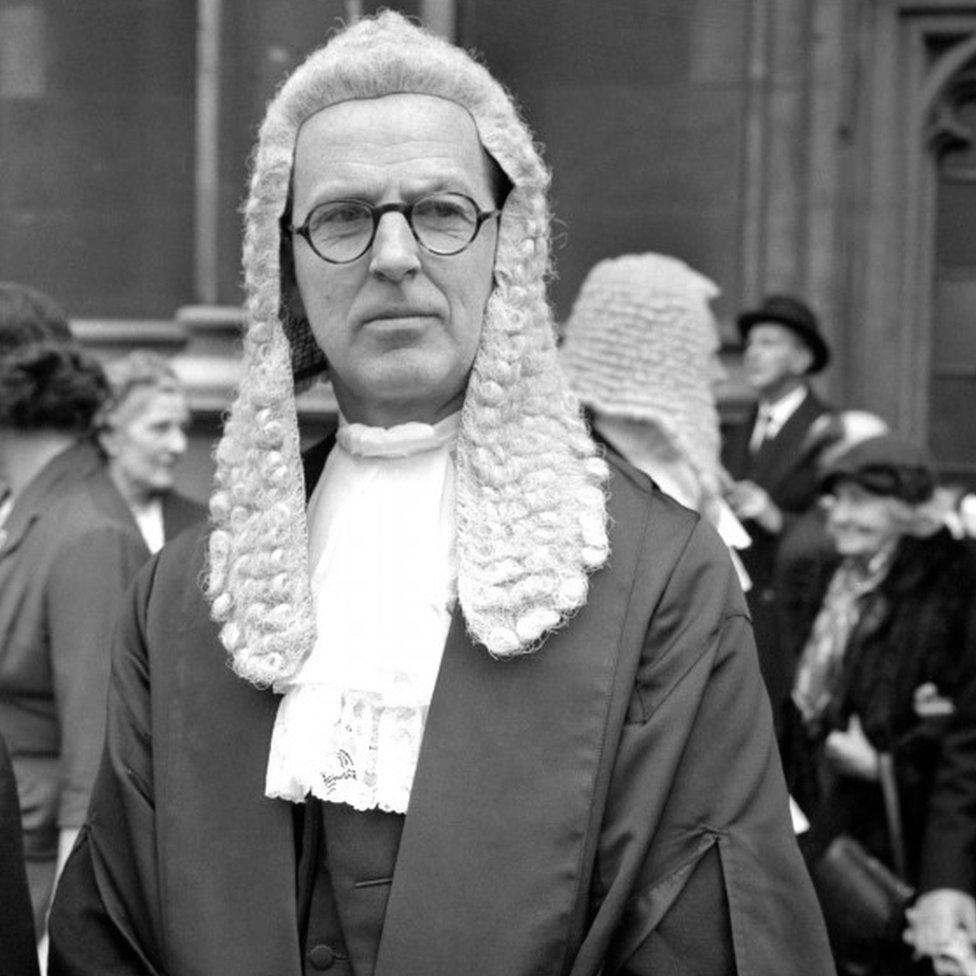

Lady Chatterley's Lover obscenity trial

The six days of the Lady Chatterley's Lover obscenity trial saw public attitudes to sex, class and the Establishment exposed to the limelight as never before. Jeremy Hutchinson was a junior barrister, part of the defence for Penguin Books which in August 1960 had published the first unexpurgated English edition edition of D H Lawrence's novel.

The case was seen as the first major test of the Obscene Publications Act which had reached the statute book just a year earlier. Hutchinson's main job was to make defence comments on jury selection. He decided that he wanted as many women as possible in the jury box because, as he later recalled, "I have always taken the view that women are so much more sensible about sex."

The trial came against a background of a growing social and sexual revolution in the UK and a post-war youth culture that was questioning many of the attitudes held by the Establishment. This view was underlined by leading counsel for the prosecution, Mervyn Griffiths-Jones who pompously asked the assembled jurors "Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?"

The end of the trial saw sales of the novel soar

Hutchinson, whose privileged background made him part of the Establishment himself, had perfected the technique of gently but mockingly pricking the pomposity of buttoned up judges and opposing counsel and this trial was meat and drink to him.

In a BBC interview he recalled his most thrilling moment was calling one of the defence witnesses, the author, E M Forster. "And then through the door came this little man in a dirty mackintosh. And I was able to say after asking him his name and address, 'I think you have written some novels.'"

The jury deliberated for three hours and returned a verdict of not guilty. Sales of the novel soared as people, many of whom had probably never heard of Lawrence, rushed out to buy it.

The theft of the Duke of Wellington

Goya began the portrait in 1812

What became Hutchinson's favourite case began when a former bus driver, Kempton Bunton, walked into a London police station in July 1965 and confessed to stealing Goya's famous portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery.

The painting had disappeared in August 1961. Over the ensuing four years Bunton sent a series of notes to the baffled police demanding £140,000 be given, first to charity and, later, to pay for TV licences for old and poor people.

The painting was eventually recovered from a left luggage locker and Hutchinson was briefed to defend Bunton, who went on trial charged with five offences including the theft of the painting and its frame.

Hutchinson decided that his defence to the charge of theft would be that Bunton had no intention of keeping the painting, therefore it had been borrowed rather than stolen. He also worked hard on the jury to be sympathetic to his client, who cut a somewhat pathetic figure in court.

Bunton was cleared of all but one charge

"I had a great ace up my sleeve," he later recalled, "which was that the ex-president of the Royal Academy, Sir Gerald Kelly, had written to the Sunday Times saying that this painting wasn't worth £140,000, and that he had doubts about its authenticity."

Eventually Bunton was cleared of four of the charges but sentenced to three months' imprisonment for the theft of the frame. His lenient sentence may partly have been due to the fact no-one could satisfactorily explain how the overweight and unfit Bunton had managed to squeeze through the toilet window through which the painting had been removed. Suspicion later fell on his much slimmer son but no charges were brought

"He was just rather a darling," said Hutchinson many years later. " I had an affection for him."

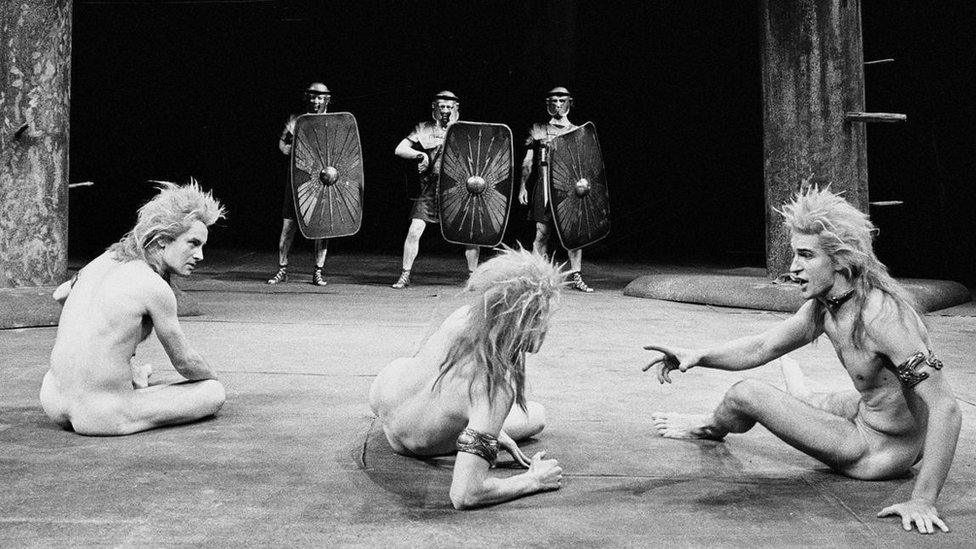

The case of The Romans in Britain

The Romans in Britain

The moral climate of 1980s Britain was far removed from the time when Hutchinson began his legal career and there were those who felt it had gone too far. Thus Hutchinson found himself defending the noted director Michael Bogdanov on a charge of permitting an act of gross indecency, instigated privately by the campaigner, Mary Whitehouse.

The charge related to Howard Brenton's play, The Romans in Britain, written as a comment on imperialism, which featured a great deal of nudity and an act of simulated anal rape which had, reportedly, seen some audience members fainting in their seats. It was the latter that formed the basis of the trial.

The chief witness for the prosecution was Graham Ross-Cornes, Mary Whitehouse's solicitor, who claimed that, from his seat in the back of the theatre, he had seen an erect penis in close proximity to a pair of male buttocks.

Hutchinson later felt some sympathy for Mary Whitehouse

Hutchinson, in cross-examination, suggested that the witness was too far away to have been able to distinguish the offending organ and suggested what had been on view was the actor's thumb.

In a move that reduced the court to laughter, the barrister made a fist beneath his gown and allowed his thumb to protrude below his waist. The case was withdrawn.

In 2016, Jeremy Hutchinson's biographer, Thomas Grant, revealed that the barrister felt some sympathy for Mrs Whitehouse who, for years was a figure of fun for the liberal classes. Grant said that Hutchinson had been disturbed by the growth in pornography and had refused to take on any more obscenity cases as he felt he could not effectively defend the material.

- Published14 November 2017