Catholics focus on the art of dying well

- Published

Father George Bowen is used to the late-night phone call. It usually comes from a family member or from a nurse at one of the two hospitals in west London where he works as a chaplain.

Often he has never met the person to whose bedside he will drive, having picked up small bottles of oil and holy water, and consecrated communion hosts.

Around the bed, he will anoint the patient with oil, talk, and pray.

"You're working in a very constrained space around the bedside," says Fr Bowen. "It's very informal. You just gather around so that everybody can hear."

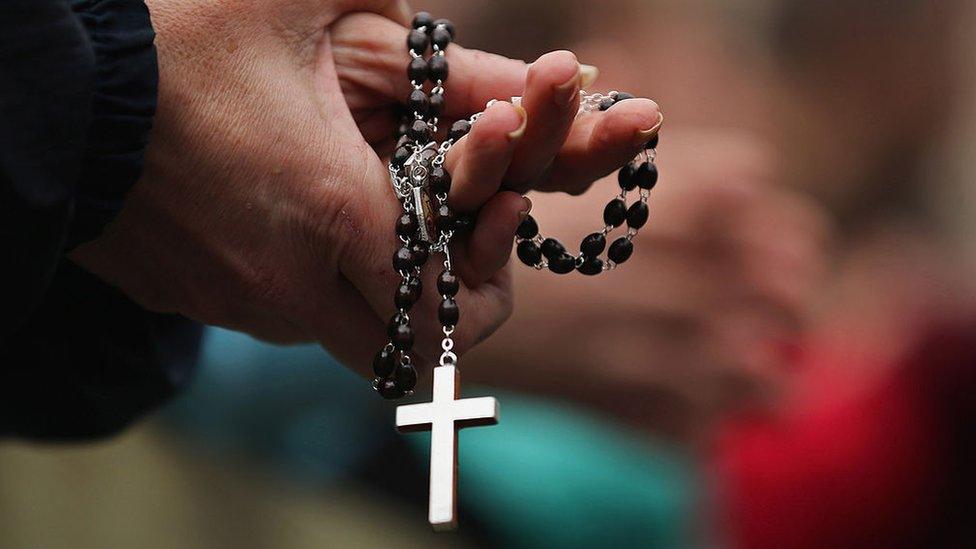

In the Christian tradition, November is the month with a black tinge, beginning with the feast days of All Saints and All Souls.

Catholics pin up lists of dead friends and family in churches, and visits are made to graveyards.

The Church is trying to promote the idea that the ideal death should be relaxed and intimate.

Dr Kathryn Mannix, a consultant in palliative care, from Newcastle upon Tyne, who has seen between 10,000 and 15,000 people in their final hours, says not knowing what dying is like is a modern phenomenon.

"We've got so good at curing people, that we ship people who are very sick off to hospital," she says.

"By the age of 30 three generations ago, people would have seen maybe a dozen deaths."

Even the physical end of someone's life, as they drift into a coma, can be unfamiliar, she says.

"It's not that you fall asleep and die, there's an irresistible drift towards a coma that doesn't feel like falling asleep," Dr Mannix says.

"It's not like on the telly or films, but that is the only current modern reference people have, so they're very frightened about that."

Just as healthcare professionals encourage women to give birth at home, Dr Mannix wants to reclaim dying as something people do in relaxed and familiar surroundings, after planning the end of their life.

The Church has launched a new website, the Art of Dying Well, external, featuring an animated film about the death of a terminally ill man who reconciles with his family before a peaceful and prayerful end.

The Vatican has banned the scattering of ashes after the cremation Roman Catholics

Its launch follows a decree from the Vatican last week, banning the scattering of ashes after a cremation.

Catholics were warned against drifting away from traditional belief, to what the Church calls pantheism, or less descript spirituality.

The Rt Rev John Sherrington, a bishop from the Catholic diocese of Westminster, said: "We need to ask people why they're doing it, find out why they're doing this, then reinforce the important point about the dignity of human remains."

The Art of Dying website coincidentally shares its name with George Harrison's 1970 song, whose lyrics appear to reject the Catholicism of "Sister Mary" and turn towards the pantheistic spirituality of Hinduism.

Dr Mannix says some of her patients take a similar approach at the end of their lives.

"People take huge comfort in things like the cycle of nature being a thing that will continue to repeat, or looking at the sky and becoming aware of their own insignificance," she says.

"As people recognise the end of their lives approaching, they become increasingly searching for spiritual meaning. That doesn't necessarily mean religious spiritual meaning."

"They're searching for what it's all about, and many people will at that stage find comfort in traditions that were familiar to them from their childhood," she says.

The Church's message is that death should be part of life.

Fr Bowen notices that on his regular car journeys back from hospital in the early mornings.

"You come away realising that you've been involved in an incredibly important moment in the lives of a lot of people," he says.

"And that gives you a shiver down the spine. It's a really, really powerful experience.

"It's in those moments that you really do get in touch with your own faith."

- Published25 October 2016