Justin Welby: Putting money in its proper place

- Published

He lives in Lambeth Palace, surrounded by priceless artefacts and can legitimately claim to be the ecclesiastical leader of more than 85 million pilgrims. But the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Reverend Justin Welby, knows the experience of having little in the way of possessions.

As a 12-year-old boy, he recalls leaving rented flats in the dead of night, tiptoeing out of several buildings because his father was unable to pay the landlord. The fees for his final two years at Eton were never paid but absorbed by the school. He has known the insecurity and humiliation of not having enough money to pay the bills.

That experience appears to have shaped his determination to hold loosely to the trappings of this world.

As he writes in his book Dethroning Mammon, which is published on Thursday: "The problem with materialism… is not that it exists, but that it dominates. It shouts so loudly that it overrides our caring about other things of greater value."

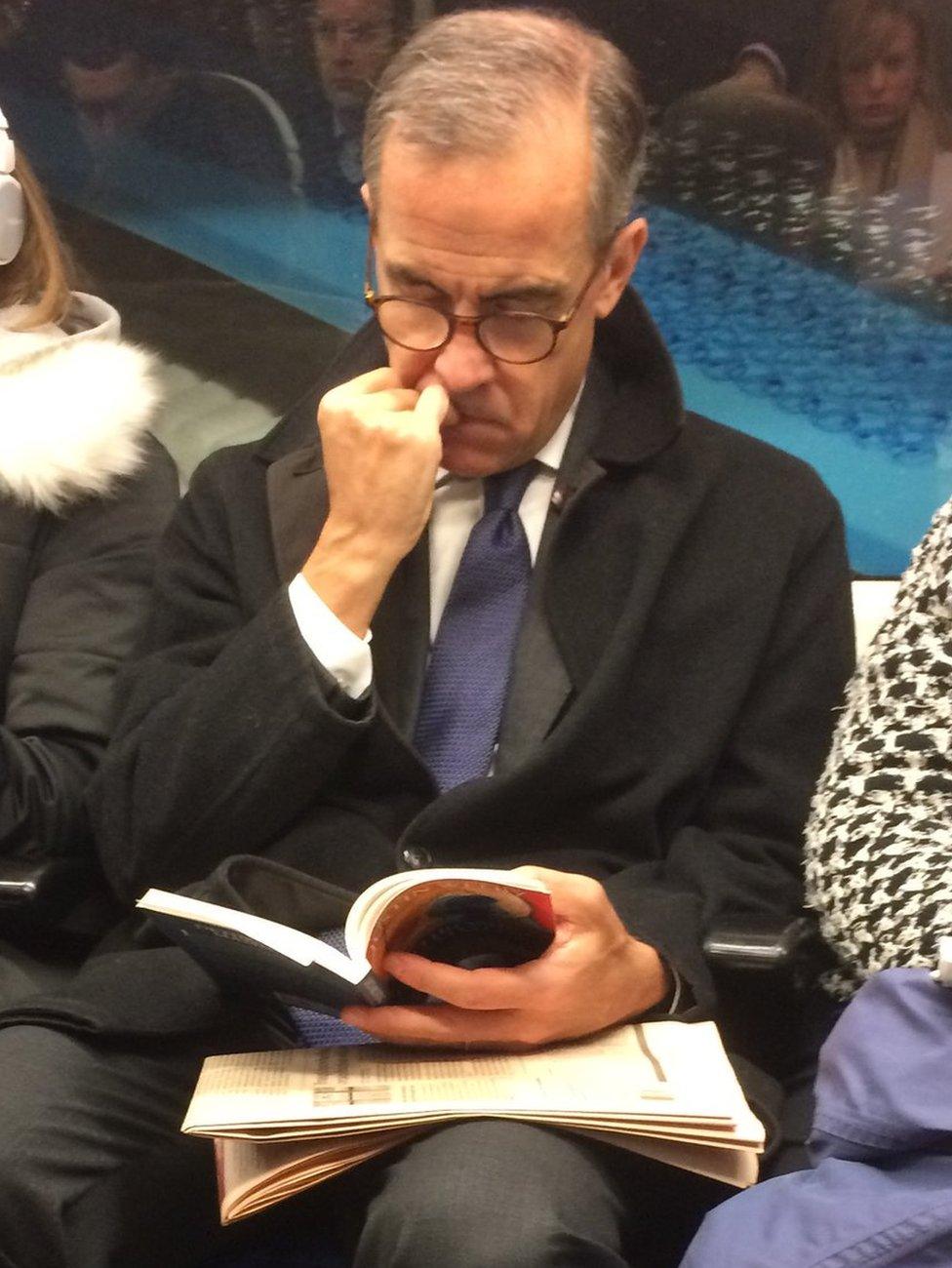

Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, has been captured on the London Underground reading a pre-publication copy - though the book is avowedly devotional and focuses on the management of personal assets and does not drift into government economic policy.

The Bank of England declined to comment about whether he had enjoyed the book.

Intended as a companion for lent, this is Archbishop Welby's first book and a call for Christians to examine who it is that sits upon the throne of their lives: are they following the self-sacrificing example of Christ, who gave his life for others? Or have they succumbed, perhaps unconsciously, to the rule of Mammon?

These are the recurrent questions that feature through a series of six short chapters, each taking what the archbishop describes as "key texts" from the Bible, which he then applies to the common settings of contemporary life.

The first four chapters attempt to deconstruct the purely materialist view of assets:

What we see we value

What we measure controls us

What we have we hold

What we receive we treat as ours

Having spent 11 years working in the energy business prior to joining the Church - rising to group treasurer of Enterprise Oil - Archbishop Welby critiques the worst excesses of City financiers who created mortgage-backed securities that tanked the global markets in 2008.

"Many bankers," he writes, "were not only aware this was a bad idea, but were also contemptuous of their clients, both the people who borrowed and the people who lent.

"To put it simply, we found ourselves with a banking system that was both out of control and uncontrollable."

Archbishop Welby questions our reliance on material consumption

In the last two chapters, he offers a couple of countermeasures:

What we give we gain

What we master brings us joy

These are what he calls the formulation of "divine economics", a kind of upside-down approach to wealth where giving does not result in depletion but blessing, and where overcoming our natural appetite for accumulating wealth is the challenge that brings genuine and deep-seated peace.

"Money buys capabilities," he says.

"It also buys security, but it risks taking us further and further away from being those who wash feet, who dethrone Mammon by subverting the power of wealth to give us a better life."

But what does a man who studied at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge know about the experience of poverty?

How can a successful oil executive, who is now the global leader of the Anglican communion, empathise with those in abject need?

It would seem that the archbishop's decision to make materialism the subject of his first book is no accident.

This book was prompted not just by his exposition of scripture but by his exposure to life.

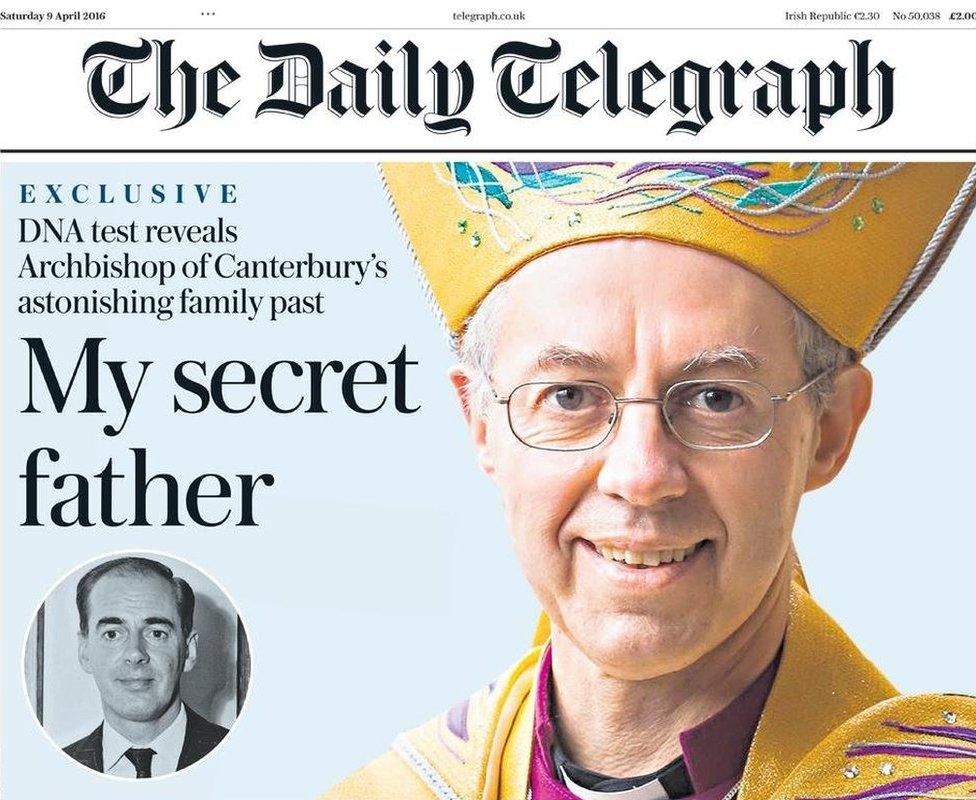

It is well-known that the man whom he believed was his father, Gavin Welby, was an abusive alcoholic who was regularly penniless.

The Daily Telegraph's former editor Charles Moore, who was told about the paternity doubt, spoke to the archbishop about his real father, Sir Anthony

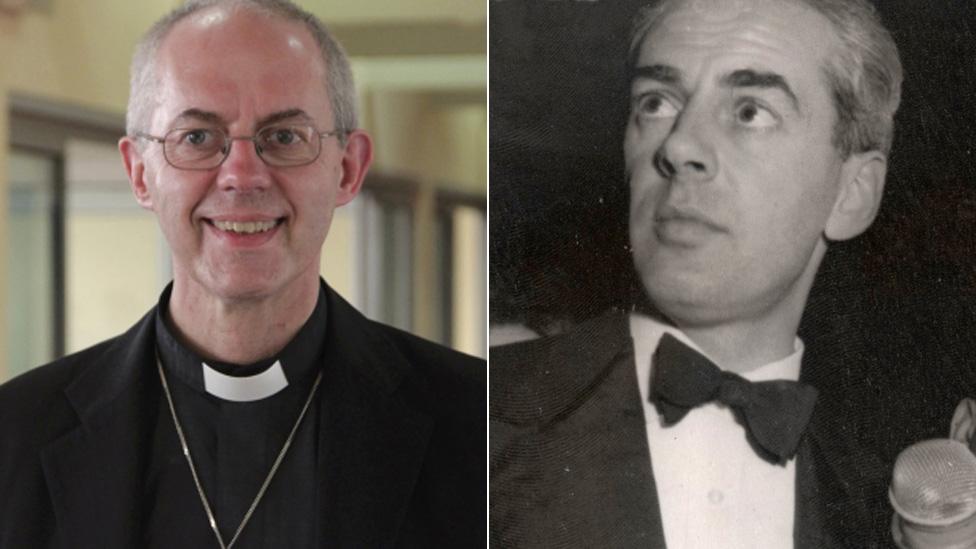

Earlier this year - after being contacted by former Daily Telegraph editor Charles Moore - the archbishop learned that Welby Sr was not his biological father.

After taking a DNA test, it was revealed that he had been fathered by Sir Winston Churchill's last private secretary, Sir Anthony Montague Browne.

It is one thing to be without possessions; it is quite another to discover the script of your parenthood has been rewritten.

The experience made him think more deeply about his personal faith.

When asked whether felt the foundations of his life had collapsed, the archbishop wrote: "I know that I find who I am in Jesus Christ, not in genetics, and my identity in Him never changes."

Archbishop Welby seems to have learned the value of possessions and people by losing them.

And his experience echoes the words of Christ in Matthew's Gospel: "For whosoever wants to save his life will lose it. But whosoever loses his life, for my sake, will find it."

Dethroning Mammon is a book about gaining through losing.

- Published9 April 2016

- Published17 February 2015