What is going wrong with the prison system?

- Published

Levels of violence are up, staff numbers are down and complaints about overcrowding are widespread. Why are prisons in England and Wales under pressure?

"There's an incident at height - the prison's in lockdown."

I was in the gate-lodge at High Down Prison in Surrey when a message came through from the governor.

BBC Special Report: Prisons under pressure , external

The Ministry of Justice - which controls prisons in England and Wales - had, unusually, granted permission for me to visit a jail for a radio documentary about prison violence.

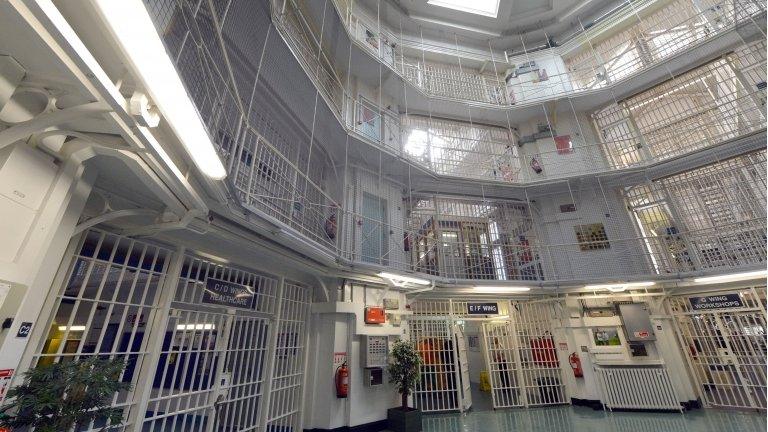

High Down prison in Surrey

They had chosen High Down, a prison built on the site of an old mental hospital and now home to 1,100 male inmates.

I waited in the visitors centre worried my visit might be cancelled, but half an hour later the incident had been resolved.

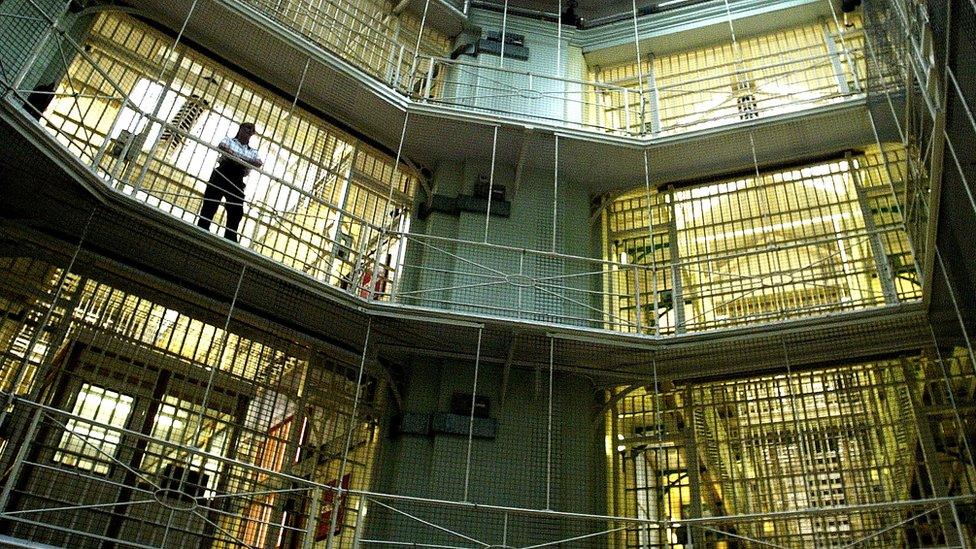

Ian Bickers, the High Down governor at the time of my visit in December 2014, brushed aside what had happened. A prisoner had clambered on to the safety netting under a landing because he was unhappy with the regime and wanted to move to another jail.

Mr Bickers explained that prisoner protests were a common occurrence, but required adept handling.

At that stage, High Down was on the edge of instability. Since then, a number of jails in England and Wales have fallen over the edge.

The footage is understood to have been filmed by inmates of HMP Birmingham

The recent disturbances at Lewes, Bedford, Birmingham and Swaleside prisons; the fatal stabbing of an inmate at Pentonville, followed by the escape of two of its prisoners; and the record number of prisoner suicides and assaults on staff all provide concrete evidence of the turmoil behind bars.

In 2015, in his last annual report as Chief Inspector of Prisons, Nick Hardwick said jails were in their worst state for a decade.

Last year, David Cameron, in one of his final domestic policy speeches as prime minister, said reoffending rates and levels of prison violence, drug-taking and self-harm "should shame us all".

Even Liz Truss, who as justice secretary has overall responsibility for prisons, acknowledges that they're "not working" and are under "serious and sustained pressure".

There have always been problems. For many years, internal reports painted a picture of daily outbreaks of violence, cell fires and self-harm across the prisons estate.

The aftermath of the 1990 Strangeways Prison riot

The worst disorder in the history of the prison service came in 1990 when two people died and hundreds were injured during rioting at Strangeways, in Manchester. It evolved into a 25-day protest against the squalid conditions and was followed by disturbances at eight other prisons.

The report into Strangeways was meant to be a watershed. It did lead to some improvements, including the beginning of the end of the practice of slopping out, where prisoners used chamber pots in their cells, but it did not herald an end to prison overcrowding.

Numbers

The principal reason is numbers. England and Wales went from almost 45,000 prisoners in 1991 to 85,000 two decades later - an increase of nearly 90%.

Justice and policing are devolved matters for Scotland and Northern Ireland. There has been nothing like the same rise in the jail population in Scotland, where the latest figure, around 7,200, is the lowest it has been for a decade. In Northern Ireland, there are some 1,500 people in custody, about 300 fewer than in the mid-1990s.

So why did numbers rise so steeply in England and Wales? Some lobby groups and criminologists point to a "moral panic" following the murder in 1993 of the toddler James Bulger.

Experts describe a sentencing "arms race" between political parties vying to be the strongest on law and order. Former Conservative leader Michael Howard's "prison works" versus former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair's "tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime".

Inside Wandsworth Prison: Trashed cells, hooch and legal highs

Whatever the reasons, average sentence lengths have crept up, more offenders have been jailed for life or indeterminate terms and growing numbers of released prisoners have had to return to custody for breaching their licence conditions.

New jails have been built, but have not kept up with demand. The Prison Reform Trust (PRT) calculates that an average of 20,000 prisoners, almost a quarter of the total, are held in overcrowded conditions. Many share cells designed for one.

At times, when Labour was in power, there was so little spare capacity that cells at police stations and in court buildings were used to hold inmates. To ease the pressure, a scheme was introduced to let prisoners out up to 18 days before their standard release date, halfway through their sentence. Eighty-thousand inmates were freed under the scheme - in addition to those released early under an existing programme which required them to wear electronic tags.

Overcrowding has a corrosive effect. It is, in the words of Strangeways report author Lord Woolf, "a cancer eating at the ability of the prison service" to deliver effective education, tackle offending behaviour and prepare prisoners for life on the outside.

Cost-cutting

When the Coalition Government came to power in 2010 it began to look for savings, as part of its effort to reduce overall public spending. Five years later the National Offender Management Service, external (NOMS), which is responsible for prisons in England and Wales, had reduced its budget by nearly a quarter.

Wandsworth Prison is one of the country's most overcrowded

Old jails that were expensive to operate were shut - 18 have closed since 2011.

But the other tactic in the efficiency drive has been a programme of "benchmarking".

Publicly run jails are required to peg their costs to the same level as the most efficient prisons, including those in the private sector.

Fourteen jails in England and Wales, and two out of 15 prisons in Scotland, are operated by private firms - G4S, Serco and Sodexo. And benchmarking has certainly led to savings. The Ministry of Justice estimates that the average annual cost of a prison place fell by 20% between 2009-10 and 2015-16 to about £35,000.

The 'core day'

Benchmarking has involved major changes to the regime in prisons and cuts to staffing. A standardised "core day" has been introduced in some jails, with the aim of making the most of prisoners' time out of their cells and giving them certainty about what activities they are doing.

But the Chief Inspector of Prisons, Peter Clarke, said jails which had brought in the new core days had not increased the amount of prisoners' time spent unlocked. Under half of jails were assessed as delivering "good" or "reasonably good" purposeful activities compared with more than two-thirds in 2009-10.

Fewer staff

With the benchmarking programme and other cost-cutting, there was a dramatic reduction in staff numbers. Posts were cut in the Northern Ireland Prison Service as well, but in Scotland staff numbers have risen.

The overall number of staff employed across the public sector prison estate in England and Wales has fallen from 45,000 in 2010 to just under 31,000 in September 2016. Although a small part of the reduction has been because of employees switching to jails transferred to the private sector, the decline is substantial by any measure, with the number of prison officers working in key front-line roles down by more than 6,000.

The jobs market in areas such as London and south-east England has been so competitive that prisons have found it hard to attract and retain replacements on a £20,500 starting salary. Many experienced prison officers have taken voluntary redundancy - with their know-how and jail-craft sorely missed. About 200 staff each month are brought in from other jails to work at prisons where vacancies cannot be filled.

Last November, members of the Prison Officers Association took part in a 24-hour walkout in protest at what they said were the "chronic staff shortages and impoverished regimes" in jails which they claimed had resulted in staff no longer being safe.

'Legal highs'

As thousands of prison staff departed, a seemingly intractable drugs problem began to arrive in jails - "legal highs", also known as new psychoactive substances (NPS). Sold under names such as Spice and Black Mamba, by 2013 the synthetic cannabis compounds had become a major problem. In contrast, Scottish prisons have had no record of any seizures of the drug.

Synthetic drugs are becoming an increasing problem in England's prisons

The health dangers, bizarre behaviour and violence associated with NPS led to them being banned in the UK last year. In prisons, they have proved to be an unpredictable, and occasionally lethal, alternative to cannabis. Between June 2013 and April 2016, the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman identified 64 deaths in jail where the prisoner was known or strongly suspected to have used or possessed NPS before they died.

Despite the dangers, these synthetic drugs are popular because they are hard to detect using conventional drug testing methods and they provide a diversion to the boredom and frustration of prison life. The drugs are a source of income for criminal gangs whose illicit use of phones and drones, combined with the help of a number of corrupt staff, has helped the trade thrive behind bars.

Watch a drone deliver drugs and mobile phones to London prisoners in April 2016

The destabilising impact of synthetic drugs, together with the loss of so many staff in such a short space of time, against a backdrop of overcrowding, has proved to be a dangerous cocktail for our prisons.

The government's policy document, entitled Prison Safety and Reform,, external published in November, acknowledges the scale of the challenge. An extra 2,500 prison officers are being recruited, there will be financial incentives for staff to stay in their jobs, while sniffer dogs and new methods of drug testing are being deployed.

Labour said the announcement was "too little, too late", saying earlier staff cuts had created a "crisis in safety".

And there are calls for far more radical measures.

Nick Clegg, deputy prime minister in the Coalition, together with the former Home Secretaries Jacqui Smith and Ken Clarke, said prisoner numbers must be steadily cut back to the levels of the early 90s, a reduction of some 40,000 inmates. "We believe that an escalating prison population has gone well beyond what is safe or sustainable," they wrote in a letter to the Times.

There are no signs, however, that Liz Truss, the justice secretary, has any intention of arbitrarily cutting the jail population. Sentencing changes and early release schemes are simply not on her agenda.

Justice Secretary Liz Truss wants to cut prisoner numbers by reducing reoffending

Michael Spurr, the chief executive of NOMS, has even gone as far as to say that he cannot see an end to prison overcrowding until at least after the next parliament - 2025, at the earliest.

Instead, Ms Truss believes that any drop in prisoner numbers should come through a reduction in reoffending - fewer people going through the revolving door of the criminal justice system.

She is hoping that extra staff and security improvements will steady the ship while longer-term changes to the management of prisons take effect. Governors will have greater autonomy, there will be closer monitoring of prison performance and education and investment in modern facilities.

HMP Berwyn in north Wales will be the UK's biggest prison

A new jail, HMP Berwyn, opens in north Wales next month. It has cost £250m to build and will house more than 2,000 male prisoners - making it the biggest prison in the UK.

The extra places will help relieve some of the pressure on a system that still relies heavily on jails constructed in the Victorian era. But more important, Berwyn sends a clear message that in spite of all the recent trouble, tensions and turmoil within prison walls, the government remains committed to the concept of imprisonment itself.

UPDATE: The graphs in this piece were updated on 2 August to reflect new figures published

- Published26 January 2017

- Published7 November 2016