Income rules for foreign spouses upheld

- Published

"If I was deported he would not have his main carer, his dad, there" - American father AJ faces deportation

Income rules which stop thousands of British citizens bringing their foreign spouse to the UK are lawful "in principle" the Supreme Court has ruled.

But children's welfare must be promoted in immigration decisions, judges said.

As of 2012, Britons must earn more than £18,600 ($23,140) before a husband or wife from outside the European Economic Area (EEA) can settle in the UK.

Judges rejected an appeal by families who argued that the rules breached their human right to a family life.

Seven Supreme Court justices hearing the case said the minimum income requirement was "acceptable in principle".

But they criticised the rules around it, saying they failed to take "proper account" of the duty to safeguard and promote the welfare of children when making decisions which affect them.

And they ruled there should be an amendment to allow alternative sources of funding, other than a salary or benefits, to be considered in a claim.

Taxpayer impact

The rules were introduced by the former coalition government to stop foreign spouses becoming reliant on taxpayers.

The minimum income threshold, which also affects people settled in the UK as refugees, rises to £22,400 ($27,870) if the couple have a child who does not have British citizenship - and then by an additional £2,400 ($2,986) for each subsequent child.

The markers replaced a previous, more general, requirement to show the Home Office that the incoming partner would not be a drain on public resources and that the couple or family could adequately support themselves.

They do not take into account the earnings of the overseas partner - even if they have higher qualifications, or are likely to be employed in higher-paid work than their British spouse.

And the threshold does not apply to spouses from within the EEA.

Visa rules "creating price on love"

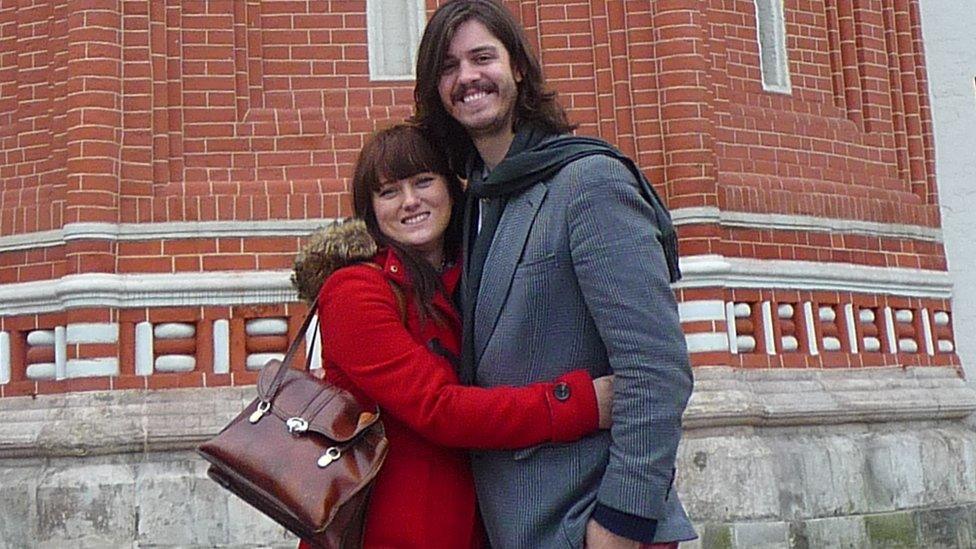

Laura Segan and Spencer Russ met while teaching English in Russia

"Just because she happens to fall in love with me and I have the wrong passport, she isn't allowed to live with me in her own country," says Spencer Russ, an American who may be deported from the UK, where he lives with his British wife, Laura Segan.

Delivering their judgement, the justices said the government's rules had the "legitimate" aim of ensuring "that the couple do not have recourse to benefits and have sufficient resources to play a full part in British life".

But they said the rules fail because they do not treat "the best interests of children as a primary consideration".

Analysis

By BBC Home Affairs correspondent, Dominic Casciani

While the couples in this case have won their appeals it's not much of a victory when the Supreme Court has clearly ruled the system is compatible with human rights.

Campaigners say they are delighted. But the government now knows the principle of the policy has been endorsed by the highest court in the land as a legitimate way to control immigration.

So what does that mean in practical terms?

The Home Office will need to make sure that each decision takes into account the rights of children - and whether a couple have other assets - perhaps a home, savings or substantial financial support from family.

That will benefit some of the families - but it also means that in the long run some of the most affected people from poorer Asian communities may still be unable to get permission to bring their husband or wife to Britain.

The justices heard appeals in February 2016 from a series of test cases.

Two claimants, Abdul Majid and Shabana Javed, are British citizens who have partners who are Pakistani nationals.

The third is a Lebanese refugee who cannot find suitable work in the UK despite his postgraduate qualifications. He says his similarly-qualified wife has high earning potential and speaks fluent English.

A final case concerns another recognised refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo whose wife has been barred from settling.

In their ruling on Wednesday, the panel, led by Supreme Court deputy president Lady Hale, held that the minimum income requirement (MIR) "is acceptable in principle", but that the rules and instructions "unlawfully fail to take proper account" of the Home Secretary's duty under the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 to have regard to the need to safeguard and promote the welfare of children when making decisions which affect them.

The court ruled on the "instructions also require amendment to allow consideration of alternative sources of funding when evaluating a claim" under Article 8 (right to private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

'Heartless' rules

Satbir Singh is a British citizen who is unable to bring his wife to the UK from India, because his more than £60,000 a year income comes from more than one source.

He said the vast majority of those affected "won't get any respite from this ruling, don't have the resources to visit each other, who might have children who are growing up without parents".

"It's terribly frustrating to find that very important components of the quality of your life are dictated by a very heartlessly thought out set of rules which seem targeted at nothing apart from achieving a certain set of numbers that the government has set for itself," he said.

'Significant victory'

A Home Office spokesman said the court had endorsed its approach in setting an income threshold for family migration that prevents burdens on the taxpayer and ensures migrant families can integrate into our communities.

"This is central to building an immigration system that works in the national interest," they said.

The current rules remained in force, they said, "but we are carefully considering what the court has said in relation to exceptional cases where the income threshold has not been met, particularly where the case involves a child".

Saira Grant, chief executive at campaigning charity the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, also welcomed the ruling - as a "real victory for families".

She said the rules had been "tearing families apart and significantly harming children".

The ruling on considering alternative funding sources was "a significant victory" and the government must now "take immediate steps to protect the welfare of children in accordance with their legal duty".

- Published22 February 2017

- Published22 February 2017