Couples speak of pain over spouse visa rules

- Published

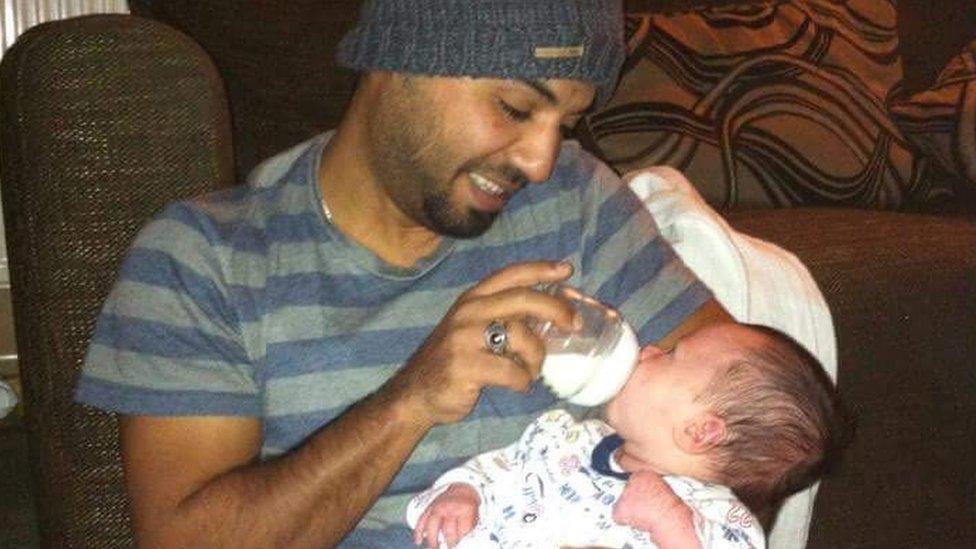

Toni Stew met her Egyptian husband Mohamed El Faramawi in 2009

Immigration rules that require a Briton to be earning a minimum amount before they can bring a non-EU spouse to the UK have been upheld in the Supreme Court. How does this policy affect families?

"My son has seen his father a few times only," says British national Toni Stew.

"I feel like a single mother rather than a wife."

Ms Stew, from Worcester, met her Egyptian husband Mohamed El Faramawi, 33, while on holiday in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2009. They got married six years later.

But, as the 25-year-old does not earn a minimum of £18,600 per year, her husband has been unable to join her and their 17-month-old son Ali in the UK.

"I feel very guilty towards my baby," she says.

"He hasn't done anything to deserve being without his father."

Ms Stew, who works as a part-time sales assistant, says she can't afford to work full-time as she also needs to care for Ali.

'Ridiculous'

They are just one couple out of thousands who are said to be unable to meet the minimum income requirement that came into force in July 2012.

Under the family migration policy, only British citizens, foreign nationals who are deemed to be "present and settled" in the UK, external, or those with refugee status can apply to sponsor their non-European partner's visa.

And whichever of those three categories they are in, they must also show they have sufficient funding. In most cases, this is proof of an annual salary of £18,600, held for at least six months prior to the application. This level rises to £22,400 for a non-European partner and child, with an additional levy of £2,400 for each additional child. The rule does not apply to EU citizens.

Those who are granted the "family of a settled person" visa cannot usually claim benefits or other public funds.

The Home Office introduced the rules as part of attempts to control immigration from outside Europe, with ministers in the then coalition government arguing that the rules would ensure no incoming families would burden the UK taxpayer.

Mohamed El Faramawi has been unable to join his son Ali in the UK

But the minimum income requirement policy was challenged in the High Court in 2013 and again in the Court of Appeal in 2014 by two British claimants and one claimant who has refugee status who want to bring their non-EU spouses to the UK.

They said the rules were discriminatory and interfered with Article 8 of the Human Rights Act, the right to a private and family life.

The case then went to the Supreme Court, which said that while family immigration rules requiring minimum income cause hardship, they are lawful.

These rules need to be changed as the income threshold is too high, the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants says.

The charity's chief executive Saira Grant says it would "greatly help" if the income of the foreign partner was taken into account.

Thousands of people are impacted by the rules, she says.

British national Laura Segan and her American husband Spencer Russ are facing the possibility of separation less than a year after they have got married.

"Just because she happens to fall in love with me and I have the wrong passport, she isn't allowed to live with me in her own country," says Spencer, 28.

His student visa expired in January and he has applied for leave to remain in the UK, but if that is rejected he fears he will have to leave the country.

Laura Segan and Spencer Russ have found their relationship complicated by visa rules

Full-time graduate student Laura would then need to earn a minimum of £18,600 per year for a minimum amount of six months in order to bring her husband back to the UK.

Laura, from Devon, says she cannot work full-time while she is studying. "It doesn't seem right," the 28-year-old says.

"I think it is ridiculous to put a financial requirement on love," adds Spencer, who met his wife when they were both teaching English in Russia.

'Computer mummy'

Andy Russell, from Bath, reluctantly describes himself as "one of the lucky ones".

"Yet I don't feel that," he says.

Molly's only contact with her family for a year was on Skype

The 43-year-old teacher faced a long battle to get his Chinese wife Molly, 36, a partner visa after they decided to move to the UK from China in 2012 with their two sons - then just three and five years old.

Molly had to return to China to apply for the visa while Andy searched for a job that met the income requirement.

She was told she could not enter the UK on a visitor visa because she had expressed her intention to get a partner visa.

A year of separation with Molly able to see her family only via Skype led to her youngest son referring to her as "computer mummy".

"It broke my heart," Andy says.

He says their sons lost the ability to speak Chinese, which affected their bond with their mother as she struggled with English, and led to them "losing some respect for her", although their relationship is "much better now".

Molly was finally granted a partner visa in 2013.

"They [the government] have got to deal with migration, but not at the expense of genuine, honest families. It is a scandal," Andy says.

The Children's Commissioner for England says that at least 15,000 children are separated from a parent because of the income rules and are growing up in "Skype families".

Andy Russell with his two sons and wife Molly before she left for China

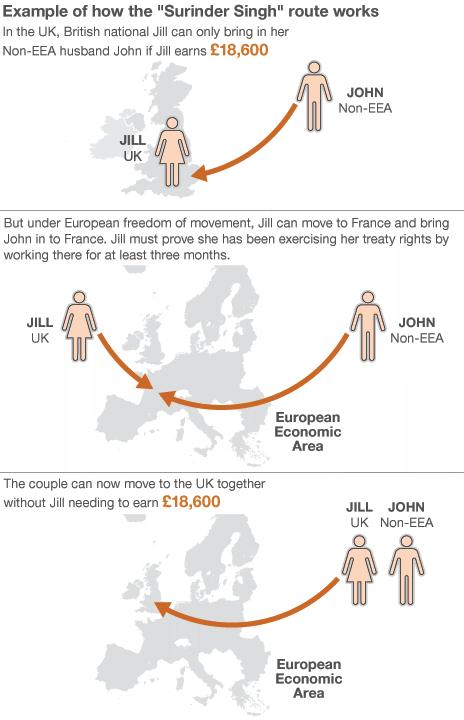

Some Britons who are unable to meet the sufficient funding requirements have used the "Surinder Singh" route to get their non-EU partners into the country. This involves working in another nation in the European Economic Area (EEA) for about three months.

It means that when they return to the UK, their case is considered under different rules - as they are treated as a citizen of the EEA rather than a British citizen.

But the Home Office must be satisfied that people who have demonstrated they did actually "move" to their new EEA country for the period they lived there and did not just simply take a short-term job there for immigration purposes.

Home Office figures show the number of partner visas granted fell from 46,906 in the year ending June 2006 to 27,345 in the year ending June 2015, when it says 66% of applications were approved.

A Home Office spokesman said those who wish to make a life in the UK were welcomed "but family life must not be established here at the taxpayer's expense".

He said that was "why we established clear rules" based on advice from the independent Migration Advisory Committee.

All cases are "considered on their individual merits," he said.

- Published22 February 2017

- Published26 November 2015

- Published15 October 2015

- Published9 September 2015

- Published13 November 2014

- Published11 July 2014

- Published26 October 2013

- Published5 July 2013

- Published25 June 2013

- Published12 June 2013

- Published10 June 2013

- Published10 June 2013

- Published6 November 2012