UK child migrant so hungry she 'ate grain meant for pigs'

- Published

Marcelle O'Brien speaks of "sadistic treatment"

A woman who was sent from England to Australia as a child was molested and left so hungry she ate grain meant for pigs, an inquiry has heard.

Marcelle O'Brien was sent to a home in Pinjarra, western Australia, run by the Fairbridge Society, at the age of four.

The then-Queen, wife of George VI, later intervened to ask whether she could return to the UK to be adopted.

But Fairbridge said it would not be in her "best interests", the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse heard.

Mrs O'Brien said she suffered "mental cruelty" and "sadistic" treatment at the home where she was forced to do "slave labour".

She was molested by her school's deputy principal and caned, the hearing was told.

The abuse scandal of the British children sent abroad

'Name the villains', abuse inquiry told

The inquiry, which covers England and Wales, heard Ms O'Brien had lived in a "loving and caring" home with a foster mother in Lingfield, Surrey, immediately before being sent abroad.

The foster mother later wrote to the Queen in an effort to get Ms O'Brien back to the UK so she could adopt her, the inquiry was told.

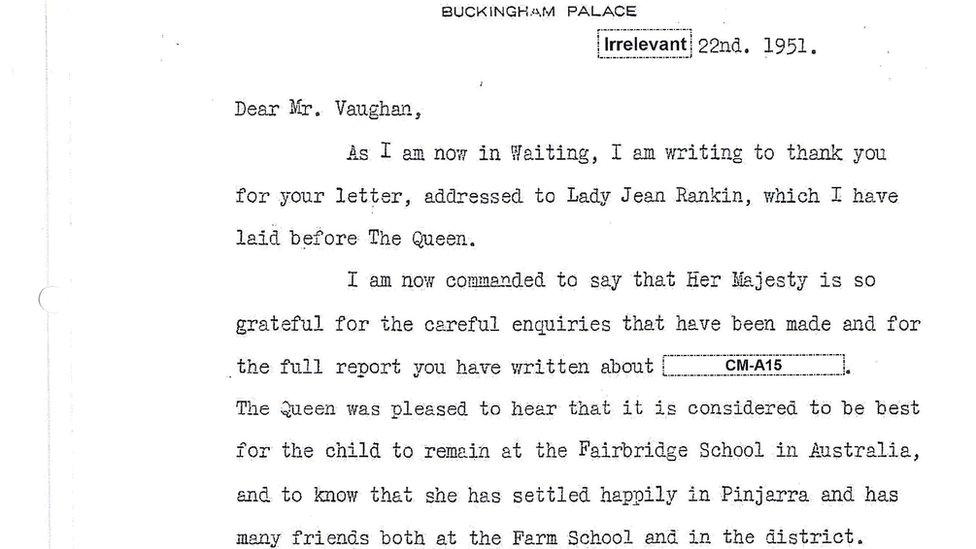

Subsequent correspondence between the Queen's Lady in Waiting and the Fairbridge Society was read out at the hearing.

A letter from the society to the Queen's Lady in Waiting said Ms O 'Brien was "happily settled at our school in Pinjarra - and which Her Majesty may remember visiting in 1928".

It went on to say Ms O 'Brien had many friends and to uproot her would "not be in the child's best interests".

The palace was apparently reassured by the Fairbridge response.

A letter from the Lady in Waiting to the society said "the Queen was pleased to hear" that it was considered to be in Ms O'Brien's interests to remain at the school.

Ms O'Brien told the inquiry panel: "They didn't take any notice. The Royal Family just didn't want to know anything. They stopped you from going back to your own original home."

Hurt and anger

Analysis by Tom Symonds, home affairs correspondent

After the tortured two-and-a half-year birth of this inquiry, it has been hard to remember the reason it was set up: namely, to allow victims of sexual abuse the opportunity to give their accounts.

The hurt and anger with which British child migrant Marcelle O'Brien has been left was plain to see. Much of the inquiry's detailed work is being done out of the public eye, so occasions like this are significant.

It was also clear that the inquiry is interested in links between child abuse and power.

The Fairbridge Society, in whose care Marcelle was trusted, had royal and establishment supporters. The evidence shows it was prepared to discredit the birth parents of its children.

But the names of the Fairbridge deputy principal that Marcelle O'Brien says indecently assaulted her, and the "cottage mother" who treated her so badly were not given, despite calls for the "guilty to be named".

This is not a court. The inquiry has no powers of prosecution, only the remit to make "findings of fact".

It is trying to avoid reaching conclusions about wrongdoing by individuals, unless they are required to show wrongdoing by institutions.

But that will not satisfy some of its critics.

The inquiry later heard from a 70-year-old British man who was sent to live at an Australian "farm school", where he was repeatedly sexually abused and raped.

Giving evidence anonymously, he said he was targeted by a group of older boys who would drag him into the bathroom or into scrub land and "make you do what they wanted you to".

He was also sexually abused by a priest and told the panel: "When he attacked you it was when you got dressed for the choir, he would make sure you were on your own and that's when he would attack you or abuse you."

The witness lives on his own and says the sexual abuse has made it difficult for him to build relationships with women.

"I've had to live with this for 62 years now. I live it 7 days a week, 24 hours a day. But you can't get it out of your mind because it's imprinted on your mind. There's no way you can get away from it," he said.

'Angry and disgusted'

Another witness, Peter Bagshaw, told the inquiry he had been sexually abused both at homes in England and after he was migrated.

In Australia, he was sexually abused by a large man "who could easily beat me up if he wanted" and he felt powerless to do anything because "I was in a strange country and knew nobody," the panel heard.

"I still feel angry and disgusted that any kid would be put through that," his statement said.

The first phase of the child sexual abuse inquiry is looking at the way organisations have protected children outside the UK.

Between 7,000 and 10,000 children were moved to Australia after World War Two.

They were recruited by religious institutions from both the Anglican and Catholic churches, or charities, including Barnardo's and the Fairbridge Society, with the aim of giving them a better life.

- Published27 February 2017

- Published6 October 2020

- Published26 February 2017