The struggle between tech companies and government

- Published

It is understood Khalid Masood's phone connected with messaging app WhatsApp minutes before the attack

The home secretary's broadside over encryption is only one part of a wider struggle with technology companies. The power of the companies has grown enormously in recent years and officials believe they have a responsibility to play more of a role in the fight against terrorism.

Last year's row between Apple and the FBI, in the wake of the San Bernardino shooting, was ostensibly about access to a specific encrypted phone used by an attacker.

But US law enforcement had long been gearing up for a battle over the issue, looking for the right moment to challenge Apple.

Some suspect the UK authorities of doing the same in the wake of the Westminster attack. If there is an issue that the government wants to press the companies on though, it is the hosting of extremist content rather than encryption.

It is not clear there is a problem getting hold of the communications of Khalid Masood in this case. But a wider principle is at stake, in which government is unhappy at the spread of end-to-end encryption.

Companies like WhatsApp will say they are providing law enforcement with assistance but they have designed their systems with end-to-end encryption, which means they are not in a position to provide the content of any communications (although the metadata, if available, can still be very useful).

In reality, the government knows that outlawing end-to-end encryption is not going to be as easy. It has just passed new legislation in the Investigatory Powers Bill and revisiting the subject seems unlikely.

A further problem is that many of the tech companies are not UK-based and the government's leverage over Silicon Valley firms has its limits.

The government may be hoping the new US administration will at some point make pressuring the companies a priority, but predicting when or how the Trump administration will act is not easy.

IS propaganda

Many of the new, smaller companies providing encrypted services are not based in America either. Telegram, for instance, provides encrypted communications but its founder Pavel Durov is thought to be based in Europe.

Larger companies point out that if they were banned from offering end-to-end encryption then their customers (and the targets of law enforcement investigation) would simply move to these smaller providers, who, they argue, are even less likely to provide assistance to governments.

They also point to all the stories about hacking and criminal theft of data as to why encryption is so valued by them and their customers.

In the UK, the responsibility of companies in counter-terrorism hit the agenda when Facebook faced criticism after it was claimed it could have done more to spot communications by one of the men who killed Lee Rigby.

That spoke to a different issue from encryption - how far should companies be monitoring the material on their sites? And when is this helping to fight terrorism and when is it spying on your own users?

The tide of propaganda created by so-called Islamic State in the last few years has pushed more attention onto what can be found on websites. Counter-terrorist officials place a high priority in restricting this content, since in their view, extremist material does not just have a radicalising effect but is directly involved in inciting acts of violence.

Amber Rudd: "Intelligence services need to be able to get into encrypted services like WhatsApp"

A meeting on extremist content had been previously scheduled for this Thursday, and comments by the home secretary and foreign secretary prioritised this issue (including the company Telegram again, which is seen as a distributor of content).

Officials want two things from the companies - a greater prioritisation of the issue and a more proactive rather than reactive stance.

YouTube says it rapidly reviews content flagged to it in order to see if it violates the company's community guidelines which prohibit things like gratuitous violence or inciting others to commit violence. But while companies maintain they do remove extremist content when it is reported to them, officials say it is not good enough.

The police run a counter-terrorism internet referral unit in which officers have the difficult task of scouring extremist sites for videos of things like beheadings and then flagging them to YouTube and others for removal.

The companies concur with almost all of their referrals. But officials ask why it is that the police are having to do this and not the companies themselves?

They point out that the companies are huge, rich enterprises full of clever people and ask why they only assign small teams to work on this subject. They want more resources both in terms of people and technology to be assigned to the task.

Companies point to the sharing of 'hashes' between platforms which relates to material they are removing so that other companies can see if similar images are also present on their sites. They have, in the past, always stressed that such activity is not automated but subject to human review.

The companies claim it is technically difficult to scan for extremist content in the same way they do for things like images that show child sex abuse. Officials say that companies that pride themselves on their cleverness should be able to find new - possibly automated - tools.

But one of the concerns of companies is that they will be seen as spying on their users. Scanning everybody's posts or messages for extremist content risks making them look intrusive.

The reality is, though, that they already scan and mine their user's data for advertising since that is primarily how companies Google and Facebook make their profits.

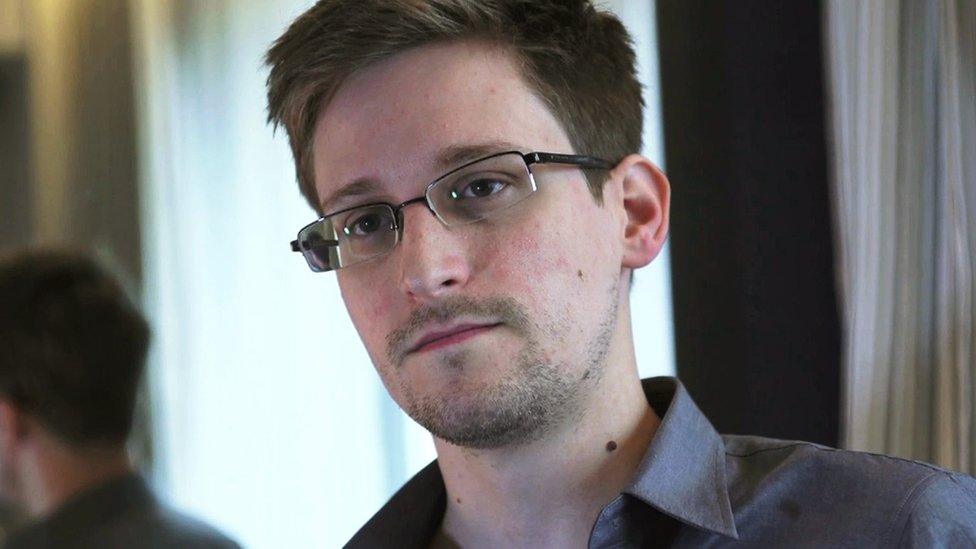

But the Edward Snowden revelations highlighted that co-operation with governments can lead to a backlash. The companies additionally are increasingly global rather than national. They fear precedents being set in one country being used in others.

What if other countries also demand extremist content is taken down but define extremist in a different way - perhaps targeting domestic political opposition? China poses a particular dilemma for the tech companies.

Apple is in the China market but it is not entirely clear what kind of data it provides to the state. Facebook is keen to get in.

Edward Snowden, a former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor, revealed extensive internet and phone surveillance by US intelligence

Although they have not ruled it out, politicians in the UK know that legislation is unlikely to be the answer to these problems. Their best bet is try to put pressure on the companies through public opinion since they are the users the companies rely on.

This tussle has been going on for years but the balance has been shifting in recent months. The fact that they have not paid much tax has helped turn public opinion against companies.

Recent revelations that they have placed advertising next to extremist content has also put them on the back foot. The companies say they are not complacent and have indicated they are willing to be more proactive and use technology in new ways. But they also will know that the pressure is mounting.

- Published27 March 2017

- Published26 March 2017

- Published25 August 2016