NHS 'robust' after cyber-attack

- Published

Home Secretary Amber Rudd said most of the NHS was now "working normally"

A total of 48 of England's NHS trusts were hit by Friday's cyber-attack, but only six are not yet back to normal, Home Secretary Amber Rudd has said.

Speaking after an emergency Cobra meeting, Ms Rudd said "there's always more" that could be done to protect against computer viruses.

She said 97% of NHS trusts were "working as normal" and there was no evidence patient data was affected.

The ransomware attack hit organisations in at least 99 countries.

Europol described it as "unprecedented" and said its cyber-crime team was working with affected countries to "mitigate the threat and assist victims".

Ms Rudd insisted the government had "the right plans" to limit the impact of the attack, which also affected the Nissan car plant in Sunderland.

'Britain left defenceless'

The Liberal Democrats and Labour have both demanded an inquiry into the cyber-attack.

Lib Dem home affairs spokesman Lord Paddick said "it has left Britain defenceless".

Labour's Jonathan Ashworth also called for a "full, independent inquiry" into the cyber-attack.

As of 21:00 BST on Saturday, the following NHS England trusts were still reporting IT difficulties on their websites:

St Bartholomew's in London

East and North Hertfordshire Trust

James Paget University Hospitals Trust, Norfolk

Southport and Ormskirk Hospital NHS Trust

Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust

York Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

The 48 NHS trusts affected did not include GP practices. Thirteen NHS bodies were also affected in Scotland.

The Scottish government said most NHS computers were expected to be operational by Monday.

NHS England said patients needing emergency treatment on Saturday evening should go to A&E or access emergency services as they normally would.

However, a small number of non-urgent services may take some time to return to normal. For example, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust has already cancelled routine appointments, tests and operations on Monday.

The malware spread quickly on Friday leaving hospitals and GPs unable to access patient data, with many doctors resorting to using pen and paper.

Their computers were locked by a ransomware program which demanded a payment to access blocked files.

Hospitals across the UK were cancelling operations and ambulances had been diverted from hospitals in some areas.

Lynne Owens, head of the National Crime Agency, said: "At this moment in time we don't know whether it's a very sophisticated criminal network or whether it's a number of individuals operating together."

Patient's story: 'Pulled out' of MRI scan

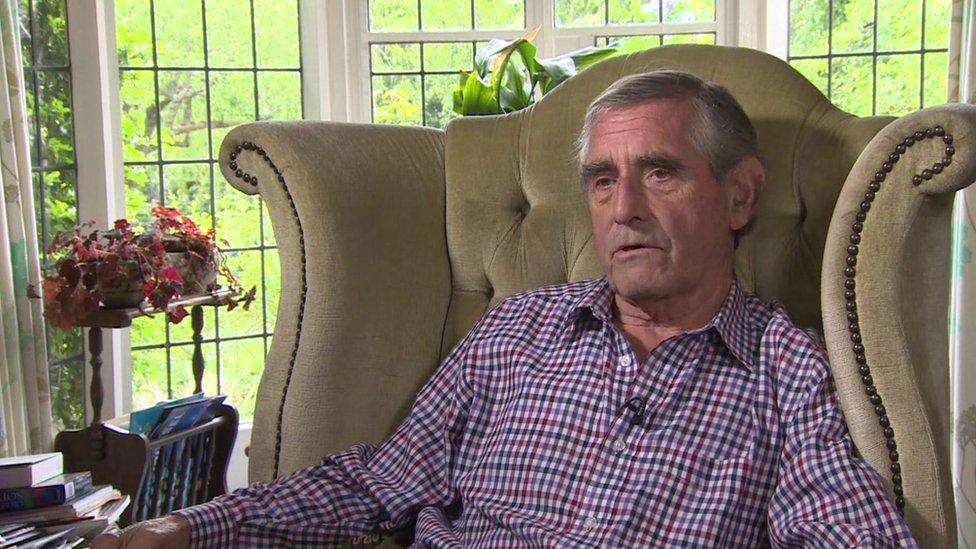

Ron Grimshaw, 80, was halfway through an MRI scan to test for prostate cancer at Lister Hospital in Stevenage, Hertfordshire, when staff became aware of the attack.

I got there at 11am, went through the usual formalities. Got my gown on, they put a feed into my wrist to send dye around my blood stream.

I was put in the scanner for 10 minutes and then I was pulled out again.

The nurses were saying something about a cyber-attack meaning their systems were down.

They weren't sure when it was going to start again so I waited for a bit. But it never happened and I went home.

I was meant to have a chest X-ray as well and that was cancelled.

I gave them my mobile number and they said they'd ring me back telling me when to come in.

You've got to sympathise with the nurses as they will have to work extra hours.

It was unbelievable you don't expect to go to hospital in the middle of a cyber-attack. Damn nuisance.

The virus, identified as WannaCry, exploits a vulnerability in Microsoft Windows software first identified by the US National Security Agency, experts have said.

Kingsley Manning, a former chairman of NHS Digital, said the government and the NHS had been "very well aware" that a cyber-attack was a threat and "significant amounts of money" had been invested "in anticipation that this sort of thing would happen".

Cyber-security responsibility

After the home secretary expressed disappointment that some health trusts were still operating computer systems on Windows XP, despite having been advised to upgrade, Mr Manning claimed that several hundred thousand computers were still running Windows XP.

He added that the government would have been aware of that.

Mr Manning told BBC Radio 4's PM programme: "Some trusts took the advice that was offered to them very seriously and acted on it and some of them may not have done.

"If you're sitting in a hard-pressed hospital in the middle of England, it is difficult to see that as a greater priority than dealing with outpatients or A&E.

"It's very difficult to get individual trusts to use the money for this purpose."

NHS Digital said that 4.7% of devices within the NHS use Windows XP, with the figure continuing to decrease.

How did the attack work?

Experts discuss the attack: "The most terrifying thing about this is how simple it is"

The ransomware used in the attack is called WannaCry and attacks Windows operating systems.

It encrypts files on a user's computer, blocking them from view, before demanding money, via an on-screen message, to access them again.

The malware seems to have spread via a computer virus known as a worm.

Unlike many other malicious programs, this one has the ability to move around a network by itself. Most others rely on humans to spread by tricking them into clicking on an attachment harbouring the attack code.

Some experts say the attackers used a weakness in Microsoft systems which is known to the US National Security Agency as "EternalBlue".

A cybersecurity researcher tweeting as @malwaretechblog has claimed to have found a way to slow down the spread of the virus after registering a domain name hidden in the malware.

He said that the malware makes a request to a domain name, but if it is live the malware stops spreading.

A security update - or patch - was released by Microsoft in March to protect against the virus, but it appears many organisations have not applied the patch - or may still be using outdated systems like Windows XP.