Cyber-attack: Europol says it was unprecedented in scale

- Published

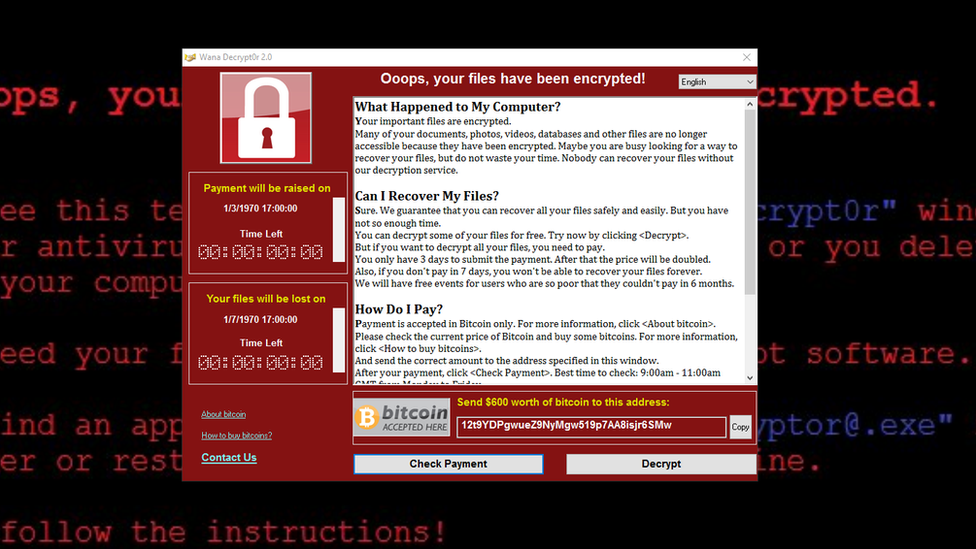

The ransomware has been identified as WannaCry - here shown in a safe environment on a security researcher's computer

A cyber-attack that hit organisations worldwide including the UK's National Health Service was "unprecedented", Europe's police agency says.

Europol also warned a "complex international investigation" was required "to identify the culprits".

Ransomware encrypted data on at least 75,000 computers in 99 countries on Friday. Payments were demanded for access to be restored.

European countries, including Russia, were among the worst hit.

Although the spread of the malware - known as WannaCry and variants of that name - appears to have slowed, the threat is not yet over.

Europol said its cyber-crime team, EC3, was working closely with affected countries to "mitigate the threat and assist victims".

NHS cyber attack: "My heart surgery was cancelled"

In the UK, a total of 48 National Health trusts were hit by Friday's cyber-attack, of which all but six are now back to normal, according to the Home Secretary Amber Rudd.

The attack left hospitals and doctors unable to access patient data, and led to the cancellation of operations and medical appointments.

Who else has been affected by the attack?

Some reports say Russia has seen more infections than any other country. Banks, the state-owned railways and a mobile phone network were hit.

Russia's interior ministry said 1,000 of its computers had been infected but the virus was swiftly dealt with and no sensitive data was compromised.

In Germany, the federal railway operator said electronic boards had been disrupted; people tweeted photos of a ticket machine, external.

France's carmaker Renault was forced to stop production at a number of sites.

Other targets have included:

Large Spanish firms - such as telecoms giant Telefonica, and utilities Iberdrola and Gas Natural

Portugal Telecom, a university computer lab, external in Italy, a local authority in Sweden

The US delivery company FedEx

Schools in China, and hospitals in Indonesia and South Korea

Coincidentally, finance ministers from the G7 group of leading industrial countries had been meeting on Friday to discuss the threat of cyber-attacks.

They pledged to work more closely on spotting vulnerabilities and assessing security measures.

How did it happen and who is behind it?

The malware spread quickly on Friday, with medical staff in the UK reportedly seeing computers go down "one by one".

NHS staff shared screenshots of the WannaCry programme, which demanded a payment of $300 (£230) in virtual currency Bitcoin to unlock the files for each computer.

The infections seem to be deployed via a worm - a program that spreads by itself between computers.

Most other malicious programs rely on humans to spread by tricking them into clicking on an attachment harbouring the attack code.

By contrast, once WannaCry is inside an organisation it will hunt down vulnerable machines and infect them too.

The BBC's Rory Cellan Jones explains how Bitcoin works

It is not clear who is behind the attack, but the tools used to carry it out are believed to have been developed by the US National Security Agency (NSA) to exploit a weakness found in Microsoft's Windows system.

This exploit - known as EternalBlue - was stolen by a group of hackers known as The Shadow Brokers, who made it freely available in April, saying it was a "protest" about US President Donald Trump.

A patch for the vulnerability was released by Microsoft in March, which would have automatically protected those computers with Windows Update enabled.

Technology explained: what is ransomware?

Microsoft said on Friday, external it would roll out the update to users of older operating systems "that no longer receive mainstream support", such Windows XP (which the NHS still largely uses), Windows 8 and Windows Server 2003.

The number of infections seems to be slowing after a "kill switch" appears to have been accidentally triggered by a UK-based cyber-security researcher tweeting as @MalwareTechBlog, external.

But in a BBC interview, he warned that it was only a temporary fix. "It is very important that people patch their systems now because there will be another one coming and it will not be stoppable by us," he said.

How a computer expert managed to slow the spread of WannaCryptor

'Accidental hero' - by Chris Foxx, technology reporter

The security researcher known online as MalwareTech was analysing the code behind the malware on Friday night when he made his discovery.

He first noticed that the malware was trying to contact an unusual web address but this address was not connected to a website, because nobody had registered it.

So, every time the malware tried to contact the mysterious website, it failed - and then set about doing its damage.

MalwareTech decided to spend £8.50 ($11) and claim the web address. By owning the web address, he could also access analytical data. But he later realised that registering the web address had also stopped the malware trying to spread itself.

"It was actually partly accidental," he told the BBC.

Have you or your company been affected by the cyber-attack? Email us at haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external

You can also contact us in the following ways:

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

WhatsApp: +447555 173285

Text an SMS or MMS to 61124 (UK) or +44 7624 800 100 (international)

- Published13 May 2017

- Published14 May 2017

- Published12 May 2017