What are UK's options over human rights laws?

- Published

The European Court of Human Rights, Strasbourg

Prime Minister Theresa May has said that the UK could opt out of some human rights laws in order to fight terrorism. How would that work?

As a party to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the UK is permitted under Article 15 to "derogate" or depart from parts of the convention in limited circumstances.

Strict limits

Derogation can happen only in "time of emergency", ie there must be a war or other public emergency "threatening the life of the nation".

If that is the case, the UK can take measures derogating from its obligations, but only to the extent strictly required by the situation.

In other words, the measures taken must be strictly limited to deal with the immediate threat and the government has to demonstrate the urgent need to suspend the UK's human rights obligations in order to protect the nation's security.

The government would need to make an assessment as to whether there was a "threat to the life of the nation" based on the recent terrorist attacks and intelligence on the level and likelihood of future attacks.

Any measures brought in must not breach the UK's other obligations under international law.

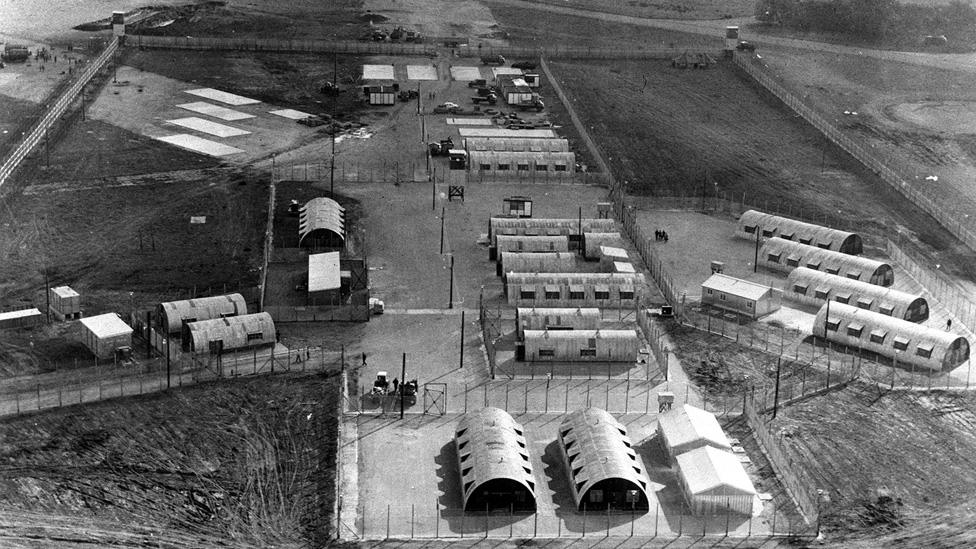

Although nothing along these lines is being considered, it is worth noting that the US's unreviewable and limitless detention of enemy combatants at Guantanamo Bay was found to be a breach of international humanitarian law by the US Supreme Court.

Guantanamo Bay

The government must also keep the secretary general of the Council of Europe fully informed of the measures and its reasons for imposing them.

Derogation can and has previously been challenged in our domestic courts and at the European Court of Human Rights.

It also requires some formal and public act, such as a declaration of martial law or state of emergency.

If that is not done, the derogation would not be lawful even though the UK might have been entitled to derogate.

Under Article 15, the judiciary and Parliament must exercise effective scrutiny over any derogation and ensure essential guarantees against the possibility of an arbitrary assessment by the government and the subsequent implementation of disproportionate measures.

What rights would the UK seek to derogate from?

Derogations are permitted in respect of Article 5, the right to liberty and security, which protects individuals against arbitrary detention by the state.

This is sometimes called internment, if it amounts to indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial.

It is not possible to derogate from Article 2, the right to life (save in respect of lawful acts of war), or Article 3, the right that protects against torture and inhuman or degrading treatment.

The UK and derogation

The UK derogated from Article 5 of the ECHR, the right to liberty and security, during the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

In 1979, the European Court of Human Rights found the circumstances of Northern Ireland, and the use of preventative detention of terrorist suspects without trial, met the criteria for derogation.

However, on another occasion the government attempted to detain terrorist suspects without charge for seven days without seeking a formal derogation of Article 5, and was found to have breached that article.

It then sought a further notice of derogation, and in 1993 survived a legal challenge at the ECHR, which found the terror threat in Northern Ireland justified the UK's measures.

The UK government interned suspected IRA members in the early 1970s in Long Kesh, a former RAF base

States signed up to the convention are given a "margin of appreciation" to depart from Article 5 in the face of threats to the life of the nation.

In this case, the UK acted within that margin.

A derogation was sought after the 9/11 attacks in 2001 in order to indefinitely detain terror suspects at Belmarsh prison.

The Law Lords (the predecessors of the Supreme Court) declared these measures disproportionate and unlawfully discriminatory because they targeted only non-UK citizens.

Lord Hoffman ruled: "The real threat to the life of the nation, in the sense of a people living in accordance with its traditional laws and political values, comes not from terrorism but from laws such as these."