Deaths in police custody 'could have been avoided'

- Published

The privatisation of healthcare is said to have led to preventable deaths

Poor healthcare in police custody has harmed patients and resulted in preventable deaths, experts claim.

The standard of treatment has rapidly declined and left people at high risk, doctors told a BBC investigation.

A move to transfer commissioning and funding decisions from police and crime commissioners to the NHS in April 2016 was overturned by then Home Secretary Theresa May.

The Home Office said commissioners knew how best to prioritise resources.

Critics say the decision was to cut costs and had led to preventable deaths.

BBC News found that most police and crime commissioners were choosing private companies to provide healthcare for people held in police custody in England and Wales.

'Decision cost lives'

Deborah Coles, director of the charity Inquest, said: "Since we have seen outsourcing and the use of private providers, the medical care of detainees has declined.

"The pursuit of profit has resulted in medical care being provided on the cheap."

She said Mrs May's decision not to transfer funding and commissioning of healthcare to the NHS "has definitely compromised standards of care… and has cost lives as a result".

A spokesperson for the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine, the body that sets standards for care and treatment in custody, said it was "a scandal" that had let down "some of the most vulnerable members of our society".

BBC News has seen a document sent to the Home Office and the Department of Health in December 2015, before Mrs May's decision, citing concerns from doctors, nurses and paramedics working in police custody for various providers including:

Patients not being examined

Numerous gaps in the rota

YouTube videos being used to train staff instead of face-to-face courses

One doctor, who worked for private provider G4S for several years, told the BBC how standards had slipped.

They said healthcare professionals with less and less experience were being employed and a lack of medical equipment, missing medication and delays in seeing patients - were all putting people at "high risk".

The doctor said when they had raised concerns, they had been told "that is just the way we do it… either you do it the way we are doing it or not at all".

Another healthcare professional, who worked for a different private provider, said standards had plummeted and "could not go any lower".

They said they had witnessed serious medical problems being missed, such as skull fractures, because "staff were not qualified enough to pick them up".

One doctor also described how induction courses for doctors working in police custody used to be intensive but had been reduced to two or three days.

G4S said all healthcare staff employed met the standards set by the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine, had to complete regular mandatory training and had a one-week induction process on joining.

The company said clinicians were encouraged to raise concerns.

A spokesman said: "We have not received any concerns from clinicians regarding a shortage of equipment, a lack of staff or sufficient training."

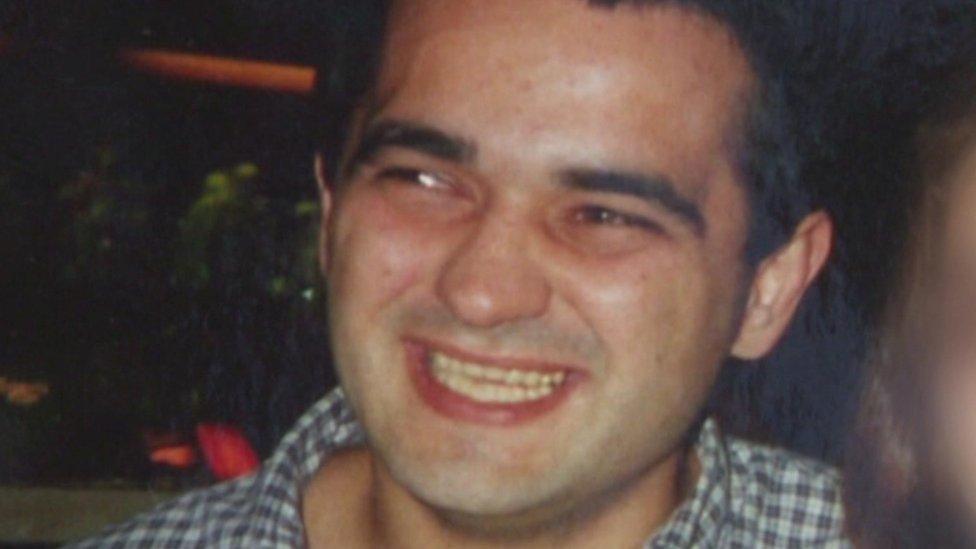

Darren Lyons, from Kidsgrove in Staffordshire, died in 2014 aged 43.

A carer called for help when she found he had locked himself in his room having failed to take essential medication.

He had a history of alcohol-related seizures and mental health issues. Instead of being taken to hospital he was taken into custody.

His mum, Diane, told the BBC that Mr Lyons had been left lying face down on the cell floor for hours, naked and covered in diarrhoea. He had a seizure and a cardiac arrest and died days later in intensive care.

The jury at his inquest found that nurses provided by a private company had failed to properly assess him and that clinical guidelines were not followed.

In a statement, Nestor Primecare Services Ltd acknowledged the jury had found failings with the care but disputed that they had contributed to or caused Mr Lyon's death.

The Home Office said police and crime commissioners were "best-placed to determine how to prioritise resources towards healthcare in police custody to meet the needs in their local area and comply with their duties".

"Many police forces have established close links to local NHS England commissioners and service providers, which has helped to enhance service standards and delivery.

"We expect such local collaboration to continue," a spokesman said.

But Dr Michael Wilks, registrar of the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine, said police and crime commissioners were not in a suitable position to commission healthcare.

"It would be like going to hospital and having an operation by someone who wasn't trained to do it, this is the level of scandal this is," he said.

In Scotland, healthcare in police custody has been funded and provided by the NHS since 2011, while the Police Service Northern Ireland directly contracts individual forensic medical officers.

Theresa May commissioned an independent review into deaths and serious incidents in police custody in July 2015 which is still yet to be published.

The BBC understands that key evidence in the review suggests that commissioning of care should be within the NHS, and that the report has been with the Home Office since January but it has still not acted on its recommendations. A Home Office spokesman said it would be released in due course.

Dr Wilks said: "There has been a growing problem in healthcare in police custody over several years.

"There is clear evidence this is costing people's lives and the government cannot justify sitting on the report a moment longer."

Faye Kirkland is a reporter for the BBC but also a working GP.

Related topics

- Published13 February 2017

- Published1 December 2016